Penny universities were safe havens for political discussion, exchange of ideas, and civil debate.

Since fall 2014, I’ve co-organized a series of informal conversations called Penny U. We’ve borrowed its name from 18th century London coffeehouses called “penny universities.” For the price of a penny, people got coffee, pamphlets, the latest news and gossip, and lively conversations on politics and science, literature and poetry, commerce and religion. The low cost led to a mingling of people from all walks of life. Anyone of any social class could frequent the coffeehouses, which became associated with equality and civil society. Penny universities became safe havens for political discussion, exchange of ideas, and civil debate.

Conversations bounce from point to point.

In much the same way that I imagine conversation proceeding at 17th century penny universities, at our Penny U, one statement or question can quickly trigger another, and conversations bounce from point to point. The discussions are less linear, more complex and varied, than “point-counterpoint,” oppositional debates on a public stage. Penny U proceeds more like loosely-focused, living room conversations, sometimes taking seemingly unrelated leaps. For the first year and a half, we focused on the nature of work, how it’s changing, and what it might look like in the future. As we move into the future, we’ve loosened our focus.

Our aim is to engage everyone in the room.

Our conversations have often been jumpstarted by ideas from speakers on Town Hall’s stages. Although these talks regularly inspire us, the premise of Penny U is that everyone with an interest who takes the initiative to attend has valuable knowledge and experience to share. Our aim is to engage everyone in the room. To encourage this, the set up is informal, and the main event happens around small cafe tables in groups of 4-5.

We begin with a topic and a bit of background, but then pose questions to prompt conversation among the small groups. Though it’s easy for the conversation to turn to big, fairly abstract ideas, we’re urged to tie big ideas to our own daily lives.

We begin with a topic and a bit of background, but then pose questions to prompt conversation among the small groups. Though it’s easy for the conversation to turn to big, fairly abstract ideas, we’re urged to tie big ideas to our own daily lives.

At the end, we reconvene as a whole to share highlights from each table, and that typically leads to more questions, more conversation, and an energy that’s often hard to stop. Notes collected at each table provide a basis for a summary which is subsequently posted online.

At the end, we reconvene as a whole to share highlights from each table, and that typically leads to more questions, more conversation, and an energy that’s often hard to stop. Notes collected at each table provide a basis for a summary which is subsequently posted online.

One thing I appreciate about our Penny U conversations is the mix of people who come. Most people are meeting for the first time, and they very often end up in conversation with people from worlds quite different from their own.

One evening, for example, we had employed workers, a couple of students, and several people who have retired though still working on some level. Among the kinds of work done by people in the room, there were artists and writers, an architect, geographer, engineer, barista, Lighthouse for the Blind worker, foster parent for dogs, and a retired carpenter, financial advisor, and stock broker. The status of their employment also varies – full-time, part-time, temporary, volunteer, independent contractor, and not working. Like early penny universities, we mix interests, ages, fields, incomes, and cultures for face-to-face conversation about things that matter.

One evening, for example, we had employed workers, a couple of students, and several people who have retired though still working on some level. Among the kinds of work done by people in the room, there were artists and writers, an architect, geographer, engineer, barista, Lighthouse for the Blind worker, foster parent for dogs, and a retired carpenter, financial advisor, and stock broker. The status of their employment also varies – full-time, part-time, temporary, volunteer, independent contractor, and not working. Like early penny universities, we mix interests, ages, fields, incomes, and cultures for face-to-face conversation about things that matter.

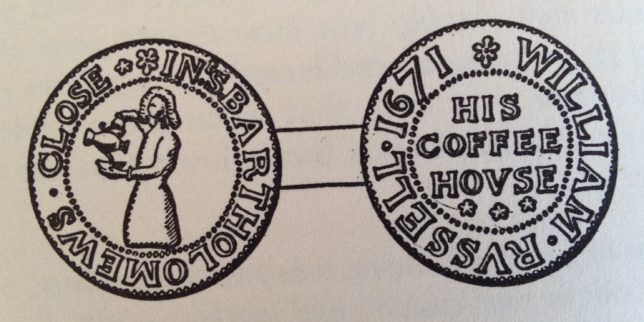

Coffeehouse pennies, or ‘tokens,’ were ‘essentially democratic.’

And, about those pennies . . . here’s a quote about coffeehouse pennies from a book about London’s penny universities in the 1600s.

In the seventeenth century, the coffee-men, in common with other tradesmen, issued their own tokens or coins. They originated through the shortage of small change and were usually for a halfpenny or farthing. For the most part they were of brass, copper, or pewter, but some were of gilded leather. They bore the name and address and calling of the issuer, the nominal value of the piece, and usually some reference to his trade. They were redeemable at the face value and were acceptable at any of the shops in the immediate neighbourhood, but they rarely circulated beyond the next street. As C. G. Williamson has said: “Tokens are essentially democratic; they would never have been issued but for the indifference of the Government to a public need; in them we have a remarkable instance of a people forcing a legislature to comply with demands both reasonable and imperative. Taken as a whole series they are homely and quaint, wanting in beauty, but not without a curious domestic art of their own.”*

««««««•»»»»»»

* Aytoun Ellis, The Penny Universities: A history of the coffee houses, first published 1956 by Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd., London, page 36.

The first Penny U at Town Hall was in October 2014, the most recent in April 2016. Penny U is co-organized by Anne Focke, at large, and Edward Wolcher, Town Hall. I posted reports from and advance notes for the first year of Penny U conversations on a different website, pennyuni.blogspot.com.

Thanks to Jean Sherrard for Penny U photos.

![]()

6 Comments