“You work too hard. You should take time to have fun, to relax and enjoy life!”

This advice from caring friends has been a kind of refrain through much of my life. Especially after turning 70 and venturing into my “eighth layer,” I find that the culture we live in assumes we will, even urges us to, slow down, stop working, or at least stop working so hard. There are many good reasons to do all these things, by choice or necessity and at various times in our lives. And I do slow down … sometimes. While over time my pace actually has changed from time to time, I can assure you that I do have fun and enjoy life. It just might not always look like it.

Over breakfast one morning I was reinforced in my apparently aberrant ways by a New York Times article I’d set aside to read weeks before.1 “Jonas Mekas Refuses to Fade,” it declared. The piece by John Leland is part of a series that looks at the lives of six New Yorkers over age 85 and how they “navigate their life at the upper end of old age in this city.”

I’d known of Mekas since the late 60s, early 70s. From afar, I learned of his life as a filmmaker, poet, organizer of avant garde film showings, and a founder of Film Anthology Archives. His life seemed tantalizing, exciting. Stories from his world fueled my own late-60s interest in the Northwest Filmmakers Co-op, the Seattle chapter of E.A.T. (Experiments in Art and Technology), and exhibitions of art using new technologies at the Henry Art Gallery.

“Mekas Refuses to Fade” showed that, even now at age 93, Mekas is still going strong. Check out his website, especially his Diary with his short video “Welcome!” at the top.2 In the New York Times article, author Leland writes:

This year [2015] alone, besides the Biennale installation, he is completing work on two books, sorting through several unfinished films, compiling his materials on Andy Warhol and the Velvet Underground for an exhibition in Paris, continuing to post video diaries on his website, and trying to raise $6 million to build a cafe and library at Anthology Film Archives, the financially struggling nonprofit institution he helped start in 1970. In between, there have been readings to give, openings and screenings to attend, new friends to meet, old ones to revisit, preferably over wine.

What motivates him to keep moving and working like this? Where does his energy come from? Leland quotes Mekas:

Something is in you that propels you. It’s part of your very essence, what you are. Like, go back to Greeks and muses. How they explained that, the muse enters you at birth or later, and you have no choice. It becomes part of you. You just have to do it.

And a little later:

I don’t feel like I’m working. It’s fun. I’m just doing what has to be done.

The science

So is there any science that might explain why Mekas is more engaged and seems more resilient than we might expect of people at the “upper end of old age”?

Leland wanted to know. So he spoke with Patricia Boyle, a neuropsychologist and researcher at the Rush Alzheimer’s Disease Center at the Rush University Medical Center in Chicago. Like others in her field had, she and her research team “observed that people who felt their life had a goal or purpose showed lower rates of memory loss and other diseases associated with age.” Doyle wanted to know why.

Their long-term study of 1,400 people, started in 1997, was designed to quantify the actual neurobiological conditions in the brain that link a sense of purpose with a lower risk of cognitive impairment like memory loss.3 They examined the brain tissues of 246 people who died during the study. The results surprised them.

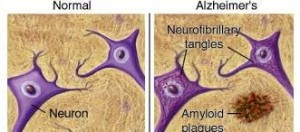

Two of the most important markers of Alzheimer’s disease in brain tissue are an accumulation of plaque and what neurologists call “tangles” in the pathways of the brain. The researchers didn’t find any difference in the level of plaque or tangles in the brains of people who had a strong sense of purpose and those who did not. As Lane Wallace in a 2012 article in The Atlantic, put it, “A strong sense of purpose does not, in other words, prevent the accumulation of potentially harmful material in the brain.”4

What the results of the researchers at Rush indicate, Wallace writes, is that having a strong sense of purpose in life, especially beyond the age of 80, can give a person’s brain the ability to sustain the harmful damage of plaque and tangles, and to continue functioning at a much higher level. I like to think of this as our brains’ ability to develop work-arounds; the researchers call it, “neural reserve.” As we learn more and more about our brains, my sense of their amazingness just continues to grow.

Wallace’s piece for The Atlantic opens with a prayer from The Egyptian Book of the Dead: “May I be given a god’s duty: a burden that matters.” Toward the end of her article, she refers to other research (specifically, work by Dr. Carol Ryff, published in the Institute of Aging):

The kind of protective effect that purposeful living offers does not accrue from mere happiness, or what researchers call “hedonistic well-being.” It would appear that humans are hard-wired a bit like working dogs – we may dream about a life of ease aboard luxury yachts, but we are at our best when we are gainfully engaged in meaningful work.

Jonas Mekas told John Leland:

My time is limited, I choose art and beauty, vague as those terms are, against ugliness and horrors in which we live today. I feel my duty not to betray those poets, scientists, saints, singers, troubadours of the past centuries who did everything so humanity would become more beautiful. I have to continue their work in my own small way.

A few more prayers from the same passage in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, are apt:

May I create words of beauty, houses of wonder. May I dance in the gyre and draw down heaven’s blessing. May I be given a god’s duty, a burden that matters. May I make of my days a thing wholly.5

And as a mission statement that Mekas wrote for a friend and that hangs on a wall in his loft says:

Keep dancing. Keep singing. Have a good drink and do not get too serious.

««««««•»»»»»»

References:

1. “Jonas Mekas Refuses to Fade,” John Leland, New York Times, October 16, 2015.

2. “Diary,” from <jonasmekas.com>.

3. “Can a Sense of Purpose Slow Alzheimer’s?” Lane Wallace, The Atlantic, May 9, 2012.

4. “Effect of Purpose in Life on the Relation Between Alzheimer Disease and Pathologic Changes on Cognitive Function in Advanced Age,” Patricia A. Boyle, Aron S. Buchman, Robert S. Wilson, Lei Yu, Julie A. Schneider, David A. Bennett, Archives of General Psychiatry, May 2012.

5. Egyptian Book of the Dead, a new translation by Normandi Ellis, Red Wheel/Weiser, 2009

![]()

Enjoyed both the piece on purpose and the one on “Time Away.” Keep writing for us, Anne!

I’ve found a rainy afternoon to read some of these wonderful posts. This one is a treasure. I need to print about 3 of the passages. How nice that it was raining today!!!