At first, whenever I had the chance to be with friends after the 2020 election results were clear, I could sense a difference in their bodies—settled shoulders, a shift in breathing, a new ease in their gait as they walk. By now, though, we know that one election, important though it is, is just a beginning.

The past four years have forced us to see below the surface of our society. What has too often been hidden away moved into the open, not just inside the halls of our Capitol, but into our streets and parks, onto our screens and social networks, and into our homes and hospitals

We face what philanthropy researcher Lucy Bernholz calls a “syndemic,” borrowing a term from medical anthropology. As she puts it, a syndemic is “what happens when an independent threat (such as a pandemic coronavirus) finds a host in a system defined by long-term, endemic afflictions and has an amplifying effect.” In a syndemic, she writes, “the dangers of individual afflictions don’t just stack on top of each other, they entwine, mutate, and grow in lethality.” And she names our other existing afflictions: “structural racism, income inequality, climate collapse, and a decades-long assault on civil society and democratic institutions.”

We have to tackle them all, finding ways we each, individually and together, can contribute to this work through our time, knowledge, expertise, and resources. Bernholz suggests ways to start, with a particular focus on confronting threats to civil society and democratic institutions.

Bernholz is a self-described “philanthropy wonk.” She is senior research scholar and director of the Digital Civil Society Lab, part of Stanford’s Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society. I’ve had the opportunity to work with her for the past twelve years on an annual forecast of big ideas that will matter in the coming year to the ways “we use private resources for public benefit in the digital age.” Her work aims most specifically to reach the philanthropic and nonprofit world, but it has relevance for all of us.

Below are the first two sections of this year’s Blueprint 2021: Philanthropy and Digital Civil Society. The entire publication, where she lays out actions for civil society and philanthropy, is available here.

— Anne Focke

![]()

MY CRI DE COEUR – Lucy Bernholz

MY CRI DE COEUR – Lucy Bernholz

The year 2020 may well be remembered as the year most universally referred to as a “dumpster fire.” I hope it comes to be seen not only for a widespread (but not yet wide enough) puncturing of White, wealthy disregard for structural injustices generally, but also, for philanthropy and the nonprofit sector, as a turning point toward more engaged, just, and equitable institutions and economics. The realization of this hope will require a sustained commitment, by individual organizations and the sector as a whole, to facing and addressing the following hard truths that 2020 laid bare.

First, despite episodic progress in the areas of basic human and civil rights throughout its history, the U.S. remains a deeply inequitable and structurally unjust country.

Second, foundations and nonprofits—many of which see themselves as part of the solution—are produced and privileged by the very same political and economic systems that perpetuate those inequities and therefore must engage in a deep analysis of their own complicity before they can hope to truly bring forward justice and equity for all.

Third, civil society is essential and not to be taken for granted. Personally, I have always distrusted American exceptionalism, since it has long been plain to me that the nation has failed to live up to its own rhetoric about equality and justice and the right of all to participate in an ongoing experiment in self-governance. Yet, I continue to believe in the promise of the rhetoric, and believe that the realization of our nation’s goals is deeply dependent on the space that lies adjacent to the formal levers of governing that we call civil society. In civil society, all those who are excluded from the “rooms where things happen” gather and organize and demand to be let in while also creating thriving alternatives. Thus did Blacks gain the franchise and fight still to keep it. Thus do people with disabilities fight for their lives and queer and transgender people demand basic dignity. Thus have Indigenous people strived for their lives, languages, and due respect of legal treaties, amid and against systems purposefully designed to take land and obliterate civilizations. What 2020 has simultaneously showed us is that civil society is responsible for laying bare these truths we all must face if we are going to build a truly equitable and just nation, and that, because of efforts to suppress people’s rights to protest and assemble, our civil society is precarious.

Fourth, digital civil society is real and vital and vulnerable, and, like it or not, all foundations and nonprofits must accept that they are part of it. After almost a year on Zoom, I am hopeful that this particular truth is obvious to many, as well as its implications. Civil society organizations are dependent on digital systems and tools to do their work: said digital systems shape their work in ways that require real tradeoffs, and the political economy of “the tech industry” influences their daily operations, their governance responsibilities, their programmatic obligations, and, indeed, the policy domains that matter to their success.

In moving forward from 2020, my cri de coeur to the philanthropy sector on behalf of civil society is that those of us who give time and money, who work for foundations or nonprofits, and who seek a more equitable and just world will abandon existing practices that are preventing many of the changes that philanthropic organizations and individuals purport to pursue. To quote Dr. Carmen Rojas, CEO of the Marguerite Casey Foundation speaking on a video conference on Philanthropy and Inequality: The Fierce Urgency of Now, “There is no scenario in which we don’t have to think hard, take risks, and change the way we work.” To move forward, philanthropists, nonprofits, and other civil society actors will have to move through deep grief, admit the failure of well-intentioned efforts, and seek different paths from those taken in the past. And across the board, people in positions of power will need to follow leaders who have been previously sidelined, while giving sustained support and control to people with the generational expertise of subjugated power.

To be specific, the philanthropic sector as a whole cannot achieve equity or justice as long as it:

- Supports toxic tax structures that prioritize the growth of the tax-exempt sector while perpetuating wealth inequality and the defunding of public services.

- Ignores the costs of dependencies that leave the sector digitally vulnerable and beholden to commercial priorities that run afoul of civil society values.

- Continues to act as a stand-in for public services, knowing it cannot actually provide the far-reaching and long-term solutions that are government responsibilities.

My hope for the years ahead is that the entire sector will abandon those practices and positioning, and instead will:

- Examine the role it plays in preserving the status quo rather than advancing change.

- Support tax reform that serves equity and social justice goals.

- Protect people’s ability to assemble, take action, and protest. This requires legal actions to protect the digital and physical means of assembly; to resource advocates and nonprofits in ways that center safety and recognize the long-term trauma of this work; and to support deeper, experience-informed research and policy about assembly in the digital age.

- Help nonprofits not just get technology, but imagine, create, purchase, and maintain a digital infrastructure and tools aligned with democratic and pluralistic logics. These are necessary to allow the sector to safely exist and remain independent of corporate and government capture.

- Develop policies, protections, platforms and new rules so that civil society and democracy can thrive in our digital reality.

- Support, amplify, and move into leadership positions those people and communities that have been fighting for equity and justice for generations, for therein lies success.

![]()

THE SYNDEMIC WE FACE AND ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR CIVIL SOCIETY AND PHILANTHROPY

While 2020 was a terrible year, much of what made it so has been in place for decades. Medical anthropology gives us a term—syndemic—to name what happens when an independent threat (such as a pandemic coronavirus) finds a host in a system defined by long-term, endemic afflictions and has an amplifying effect. In a syndemic, the dangers of individual afflictions don’t just stack on top of each other, they entwine, mutate, and grow in lethality. Such has been the case this year in the United States, where the Covid-19 pandemic arrived and amplified the existing afflictions of structural racism, income inequality, climate collapse, and a decades-long assault on civil society and democratic institutions.

The affliction that is the assault on civil society and democracy, and the way it intersects with the philanthropy sector, is of particular relevance to this Blueprint because it is from within civil society that many fights for equity and the protection of our democratic principles first take place, and it is the mission of many in the philanthropic sector to support these fights. This is to say that civil society is as critical to the functioning of democracy as are verified and trustworthy voting machines. And a healthy philanthropy sector has an important role to play in the preservation and promotion of civil society.

And the affliction is real: In the decade since I began writing the Blueprint series, there have been numerous efforts to change the rules for U.S. civil society, which have in turn impacted philanthropy. In 2010, for example, the U.S. Supreme Court handed down a decision in the case of Citizens United v. FEC. The case (along with others, such as McCutcheon v. FEC) changed campaign finance law in the United States and legitimized the idea of corporate personhood. These decisions created the opportunity for political donors to use charitable nonprofits as a means of laundering their names off of political contributions and as such have had a huge impact on the philanthropy sector.

Ten years on, the effects of this are seen not only during election cycles but in the everyday workings of U.S. civil society. There seems to have been growth in the number and size of organizations deliberately using charitable (c 3) and political (c 4) structures to pursue missions through legal struggles that seem almost anachronistic given the extensive and deliberate efforts to blur lines between the charitable, political, and corporate sectors. (The data on this are bad, which is a fixable problem.) By contrast, individual donors at all levels mix and match political behavior—both action and giving—with charitable behavior, and they are focused much more on issues and causes than on legal categories.(1) In parallel, the importance of tax benefits for certain activities and not others appears relevant to fewer and fewer donors, although much more research on this is necessary.(2)

At the same time, the oversight body for the charitable sector (the IRS) has been steadily gutted of funding over decades. And the last year brought on an adjacent effort to defang the oversight body for political organizations (the FEC) by encouraging the resignation of commissioners (and not replacing them) until there was no longer a quorum.

Meanwhile, attacks on the U.S. electoral system have been continual and unrelenting since the 2000 Bush v. Gore Supreme Court ruling to end vote tallying in Florida and declare George W. Bush president of the United States based on the standings in the electoral college. More recently, in 2011, the Republican Party undertook a successful effort to redistrict Congressional districts that was so nefarious that the book about it is titled Ratf*cked. Similarly, fundamental protections of the Voting Rights Act were stripped away (again by the Supreme Court) in 2013; between 2013 and 2020, the State of Georgia threw 198,351 voters (most of whom are Black people) off the rolls under false pretenses, while also installing election machines known to be faulty, and to ice the cake, installing far too few of those;(3) and in Florida, after voters passed a referendum re-enfranchising formerly incarcerated state residents, the state legislature simply overruled the will of the voters and put new roadblocks in place, again stripping more than one million people (most of whom are Black or Latinx) of the most basic right of citizenship in democracies, the ability to vote. Indeed, though it takes different forms, voter suppression, largely of people of color, remains a hallmark of the U.S. electoral process. As Professor Eddie Glaude has written about the U.S., “Our democratic principles do not exist in a space apart from our national commitment to white supremacy.”(4)

If all that isn’t sufficient, civil society has been threatened by efforts to limit protest and suppress assembly, two of its bedrock elements. Ironically, those who so often use the First Amendment right to free speech to champion rules that expand money in politics seem to hold little regard for the right to free assembly or petitioning the government. Since 2016 alone, forty states have considered more than 135 proposals for legislation or regulations to limit protest, including one in Florida that would grant immunity to drivers who hit people assembled on the streets.(5) In October, 2020, The Wall Street Journal reported more than 100 such incidents since the start of the year, leading to charges against 39 drivers.(6) For the last four years the president of the United States has made numerous overt call-outs to armed vigilantes, organized within civil society, to take to the streets in what he, without irony, refers to as “law and order.”

Digital tools also provide a slew of new opportunities to close the space for assembly and association. Unlike many parts of the world, where shutting off the internet is an oft-used blunt-force tool, authorities in the U.S. have seemed to prefer more invidious tactics. One example comes from decisions to maintain the porous ties between corporate data gathering and government surveillance that Edward Snowden revealed seven years ago. Another is the regulatory inaction that consistently allows a handful of corporations to set the rules that control speech—with politicians pursuing regulation only when their own speech is deemed in violation of corporate codes.

Further, digital surveillance is easily advanced by providing funding to police forces to invest in privacy-invading surveillance equipment. This funding comes from both the federal government and the private sector, both of which often help police departments conceal these purchases from public oversight by funneling them through nonprofit police foundations. Communities have also digitized their public spaces with ever-present cameras, license plate-readers, and “smart” sensors on everything from parking garages to streetlamps. These installations, marketed in the name of security or efficiency, extend corporate data collection practices and business models beyond our computers and into the public spaces where we assemble.

While advocates and scholars have been focusing on the dangers posed by online misinformation and corporate speech moderation, all-seeing digital data collection mechanisms have left the “screen” and been placed throughout our “public squares.”

As for the philanthropic sector, what 2020 has done, to paraphrase Warren Buffet, has shown us the real ground we’re standing on when the tide pulls out. On that ground, what has been revealed is that truths long visceral to those exploited by the system have been made unignorably visible to those who benefit from it. For example, most philanthropic organizations are led by White people, resulting in stark disparities in funding provided to nonprofits run by Black, Indigenous, or people of color. Indeed, Black-led nonprofits face a philanthropic world that is as biased as that confronting Black-owned businesses seeking credit or Black families seeking mortgages. And let us be clear about politics: while philanthropy is comprised of many organizations committed to redressing syndemic harms, it is also home to donors and activists who embrace market fundamentalism, White supremacy, climate change denial, and the inequitable treatment of women, LGBTQ people, and immigrants. While many nonprofit and philanthropic organizations care about equity, many do not.

Many philanthropists insist that they provide support in an apolitical way. But since the institutional philanthropic world exists as an artifact of political choices—the tax and corporate code, first among them—this is simply not possible.(7) The more compelling evidence against this pretense of apolitical existence exists in the decades of successful efforts by right wing foundations and nonprofits to change the rules of the game. There’s good scholarship on the Republican Party’s efforts to change the rules of governing over the last twenty years. Most of this literature centers on strategies that focus directly on elections and governing—voter suppression, gerrymandering, social media manipulation, and court packing. Much has also been written about the economic policies that accompany this political behavior, including deregulation, the elevation of techno-libertarianism, and the privatization of public services. Not enough has been written or considered about how the same aspirations to change the rules manifest in civil society. But they do.

The fact is, while giving and caring for others are human values that pre-date any form of government and extend across cultures, languages, time, and place, foundations and nonprofits—along with donor-advised funds, LLCs, political action committees, political parties, social enterprises, family offices, and trust companies—are institutions sanctioned, chartered, and regulated by governments and sold by lawyers, bankers, and wealth advisors. Unlike the basic human instinct to give and care for others, they are regulated products, bound by government rules and market incentives.

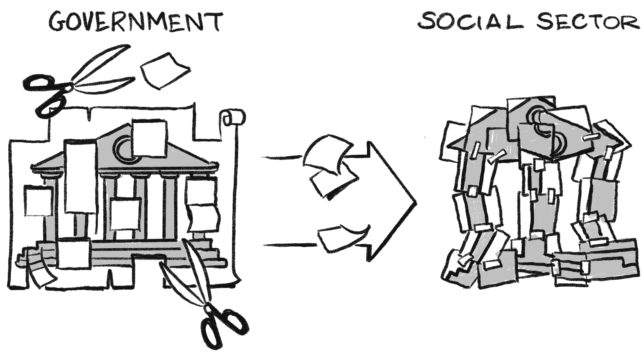

The fact is foundations and nonprofits are products of toxic tax policies that use the promise of philanthropy to justify inequality. In the United States today, our current tax laws starve our schools, hospitals, transit, and elder care systems. They allow individuals to become trillionaires and corporations to pay nothing. They encourage companies to hide marketing expenses as charitable donations, enabling corporate price gouging in the name of benevolence.(8) And they enable the amassing of philanthropic fortunes so large that people turn to them when government efforts fail, which is exactly what we have seen during the Covid-19 pandemic. Philanthropic institutions stepped in to provide basic protective equipment for frontline workers when the federal government abdicated this responsibility. They shipped masks and gloves to places that needed them, upped donations to food banks, and provided money to and negotiated with hotels to enable homeless people to quarantine. They donated hardware and software to help students attend remote classes. And they provided hundreds of millions of dollars in grants to state governments to protect the November election, a public responsibility that cannot possibly be seen as an appropriate role for private actors.(9)

Yet philanthropic fortunes, created at the expense of shared investment in government programs, will not and cannot remedy the afflictions that are at work in the current syndemic, such as structural racism; inequitable health care, education and housing; or insufficient efforts to halt climate change. Those failures are ours collectively, as citizens. Only together can we solve them. It isn’t simply that the funding doesn’t add up, it’s that relying on philanthropy and nonprofits to do the public’s work is a form of lower-cost outsourcing with less accountability. It’s not democratic. And it’s not working.

To put it another way: any reader will be familiar with the claim—made during previous economic crises—that some companies or industries are too big to fail. What the syndemic we face now shows us is that our current philanthropic sector is too big to succeed. Philanthropy has become so big partly because of government priorities that put a higher value on capital accumulation and private wealth than on public well-being, but it’s not big enough to replace government. In an ouroboric irony that must be called out: we’ve starved our public systems to encourage private action, knowing full well that private actors are neither able to nor appropriate for meeting public needs. Indeed, as generous as they have been during this crisis, foundations will slow their giving as soon as their endowments begin to shrink, or they get bored of paying for basic services. And they could never even hope to begin covering the cuts resulting from state budgets decimated by Covid-19. The broader process at work here is one of privatization—of public responsibilities, of government functions, of accountability—and it is a trajectory toward failure.(10)

What most distresses me is the degree to which many in the sector are acting as if everything is OK, we just need more philanthropy and we need it now. Decades of tax and corporate regulations to minimize tax bills for the wealthy and induce more philanthropy have brought us to this moment. Moreover, the sector’s own infatuation with size (as measured by assets, percentage of GDP, and jobs) is an accelerant to political frames that minimize public investment and decrease public services. In using its size and scale as political leverage, and in refusing to take on policy issues that might limit the growth of philanthropy, the sector contributes to the privatization of public obligations. We don’t need more philanthropy covering our basic public responsibilities. We need public resources, public governance, and public accountability.

More philanthropy will not get us to a just or equitable society. Philanthropy done better will help, but more fundamentally, what is needed is an honest evaluation of what we’ve let philanthropy become and where it should fit in relationship to public responsibilities. In order to overcome the syndemic that is upon us, we need to reclaim public control over the corporations and technologies that shape our right to speech, assembly, association, and privacy, and to overturn public policies that protect those rights for some people (White, wealthy) and not others. We need to repair the long-term damage of racism—in society writ large of course, but also in the sector—before we can even arrive at a starting line for pursuing equity.

We need an economic overhaul that prioritizes human dignity over wealth hoarding. And we need to listen to the wisdom and follow the lead of people whom our systems have always oppressed, for they are the ones most experienced in imagining and working toward liberation.

Read more: All of Philanthropy and Digital Civil Society: Blueprint 2021 is available here.

![]()

Endnotes

- Laurie E Paarlberg, Rebecca Nesbit, Richard M. Clerkin, (2019) “The Politics of Donations: Are Red Counties More Donative than Blue Counties,” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, (48:2) and Maria Petrova, Ricardo Perez-Truglia, Andrei Simonv, and Pinar Yildirim, “Are Political and Charitable Giving Substitutes? Evidence from the United States,” Petrova, Maria and Perez-Truglia, Ricardo and Simonov, Andrei and Yildirim, Pinar, “Are Political and Charitable Giving Substitutes? Evidence from the United States.” (December 22, 2019). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3508534 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3508534

- According to tax experts, about 8% of U.S. tax filings took advantage of charitable tax exemptions following changes in the law that went into effect in 2018. Prior to these changes, between 25-30% of tax filers claimed charitable tax deductions. In addition, conversations with more than 300 people over the course of 2019 and observations of behavior on crowdfunding platforms and the creation of LLCs instead of foundations imply that tax benefits are of decreasing importance to both every day and high net worth donors. My book, How We Give Now, exploring this in more detail, published by The MIT Press will be available in the fall of 2021.

- Greg Palast and the Palast Investigative Fund, “Georgia Voter Roll Purge Errors,” September 1, 2020, Report for the ACLU, accessed online: https://www.acluga.org/sites/default/files/georgia_voter_roll_purge_errors_report.pdf

- Eddie S. Glaude, Democracy in Black: How Race Still Enslaves The American Soul, New York, NY: Crown Books, 2017, p. 6.

- Desiree Stennet, Monivette Cordeiro, Katie Rice and Grace Toohey, “Florida protest laws could be harshest in nation under DeSantis proposal,” Orlando Sentinel, September 23, 2020, accessed online https://www.orlandosentinel.com/news/ orida/os-ne-desantis-protest-bill-opposition-20200923-ihsipkhwdncorouj4whycypss4-story.html

- Donald Morrison, “Cars Have Hit Protestors More than 100 Times this Year,” The Wall Street Journal, October 25, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/cars-have-hit-protesters-more-than-100-times-this-year-11603645201

- Rob Reich introduced me to this idea.

- Nicholas Florko, “’You just got better at making money’: Democrats blast Celgene, Teva for price hikes detailed in internal documents,” Stat, September 30, 2020, accessed online https://www.statnews.com/2020/09/30/democrats-drug-pricing-celgene-teva/

- Kenneth P. Vogel, “Short of Money to Run Elections, Local Authorities Turn to Private Funds,” The New York Times, September 25, 2020, accessed online: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/09/25/us/politics/elections-private-grants-zuckerberg.html

- Chiara Cordelli, The Privatized State, Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020.

![]()

![]() References

References

- Ben Crothers has been the illustrator for the Blueprint series since 2018. http://brightpilots.com

- The the full version of Philanthropy and Digital Civil Society: Blueprint 2021 is available for free download at: https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/publication/philanthropy-and-digital-civil-society-blueprint-2021/

- The entire Blueprint series is available here: https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/resources/blueprints

- The website for the Digital Civil Society Lab is: https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/research/digital-civil-society-lab/

- Many of the same topics are covered in a new book, Digital Technology and Democratic Theory, edited by Lucy Bernholz, Hélène Landemore, and Rob Reich, University of Chicago Press, February 2021. https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/digital-technology-and-democratic-theory/

- Recording of the livestreamed conversation and book launch for Digital Technology and Democratic Theory: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wLO3YjTcFxc

![]()

Thank for sharing this Anne. It’s tremendously important & so timely! Has Lucy been in touch with Edgar Villanueva and DeColonizing Wealth? He’s hosting a conversation on these issues in the next week. I’ll post a link later.

Thanks for the note, Anne! Lucy mentions Villanueva and his work in the Blueprint linked above. Under the heading, “Toward Philanthropic Reform” as part of her section on “Future Promise,” she writes: “The work of Edgar Villanueva and others on decolonizing wealth that seeks different ways of being is gaining attention alongside calls for a new economy, cries about late capitalism, and generational leadership of old fortunes.”

You probably already have it, Anne, but for others, in the resource list at the end of the Blueprint, Lucy includes a link to Villanueva’s book: “Decolonizing Wealth: Indigenous Wisdom to Heal Divides and Restore Balance.”

In fact, the extensive resource list is one of the treasures of this issue. She calls it “Where to go for more.”