“An aging United States reduces the economy’s growth – big time,” claimed Robert J. Samuelson in the opening line of his 2016 news story in the Washington Post. The story referred to an academic study of economic slowdown as we’ve seen it in recent years. Samuelson and the study traced this decline to our aging population. In fact, after presenting many details from the study, he concluded that, “If other economists confirm the study, we’d probably resolve the ferocious debate about what causes economic slowdown. The aging effect would dwarf other alleged causes…” It’s an interesting theory, but I argue with some of the conclusions he draws and offer another conclusion of my own.

By itself, the opening line immediately reminded me of a homegrown theory I’ve tossed around informally for some time. I tend to pull it out in conversation whenever I or someone else in my general age bracket expresses concern about whether or not our money will last as long as our lives will.

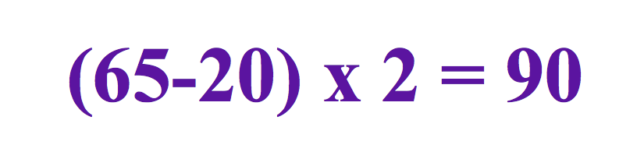

As a mathematical equation, my idea might look like this:

There may be a better way to express it mathematically, but here’s how I tell the story:

Using round numbers, I say, imagine that I started earning my own living at age 20. I was actually a little older than that, but it’s close enough, and saying I was 20 makes the equation easy to figure out. Then suppose that I decided to stop working for pay at the societally-accepted “retirement age” of 65. I didn’t, but again I’m not quibbling about details. The kicker comes when we add the final assumption, that I might live to be 90. The average life expectancy for a woman my age has been going up and is currently about 86.5 years – again, the number is close enough for the purpose of my storytelling.

The simple arithmetic of the story suggests a conclusion.

Someone living according to this equation would have an earning life of 45 years, that is, 65 minus 20. And that’s just half of a full 90-year lifetime. Hmmm . . . that seems to imply we’d have 45 years to generate 90 years of living expenses, two years’ worth for every year worked. The equation is all too simple, I know, since it doesn’t account for many things. All the same, applied to real life, the equation sets a crazy expectation.

“Oh, but wait!” you may say. “You haven’t accounted for the fact that your 45 earning years really only have to pay for your extra 25 years after retirement. That’s not quite so bad.” Ah, but I’d counter, consider that my first 20 years were hardly free. Somebodyhad to pay for them. In my case, it was my parents, and anyone who’s a parent knows they’re paying for at least two lives during the first 20 years of their child’s lives. But whether I’m a parent or not, I think my equation has to account for the cost of those years. So, I argue, the equation holds.

Obviously, a certain segment of the population with high earnings (especially if boosted by inherited wealth) can, indeed, pay for 90 years of life with just 45 years of work. For most of us, though, the economic life my equation points to is probably difficult if not impossible, and on the scale of an entire society, it’s hard to believe that the formula could possibly work at all.

My equation, though based on an individual life, has broad implications for an aging society overall. For me, it clarifies why an aging population that depends for its livelihood in our current economic system could be seen as a cause of economic slowdown. Clearly, a steep earnings decline follows retirement for many of us.

In his discussion of aging and economics, Samuelson discusses the study’s explanations for why an increasingly older population might have a dampening effect on economic productivity. For one, the decline is partly based on the proportionally smaller number of workers left to support production. But the study also reports that this accounts for only about a third of the decrease.

One theory for the rest, Samuelson proposes, is that older people may be more cautious with their spending, valuing stability and being more restrained, of being less experimental and optimistic in their views and actions. To this one I say, for myself at least, “Bah, humbug!” My desire to respond to the urgencies of today – climate crisis, justice and inequality, the precarious state of our civil society – has only increased at age 74, especially since I know my time is limited. I may act in different ways than I did in my 20s, but I’m no more cautious or restrained.

Besides, my homemade equation suggests that the “cautious spending” of older populations is not necessarily about our reduced sense of experimentation and adventure but rather about the reduced size of our bank accounts. My simple arithmetic speaks to larger questions about how our economy works, or more accurately, doesn’t work. For one thing, the only work that our current economy values is work exchanged for money.

What do you think older people are doing in their “retirements,” that is, if they’re lucky enough not to be scrabbling for money to pay the rent? Countless numbers of us are contributing in valuable ways to our communities, and more could. Look at the hair color of volunteers at food banks, in legal clinics, in libraries, and at other nonprofit and voluntary organizations. Who’s taking food to shut-ins? Who’s regularly writing their elected officials and participating in other ways in our democracy? And then there are the grandmothers and grandfathers! Yes, we love the time we spend with our grandchildren, but in many cases grandparents play an essential role in helping cover the cost of their grandkids’ first 20 years. It may be loving, but it’s still work.

Are we only able to put our effort to these things if we’ve been lucky enough to have held jobs for 45 years that pay double-time? We need to change the economic arithmetic. We need a different formula.

![]()

Note: The Washington Post article, published on August 21, 2016, can be found here.

![]()