As many of us did, after the 2016 election Boting Zhang asked herself, “What’s a plebian to do?” I’m inspired by how quickly she responded. Since her childhood in China, Bo had carried in mind a dream of America as meiguo, the Beautiful Country. In late 2016, this dream from her childhood compelled her to leap into the polarized space that divides much of this nation. To try to understand the divide and, if possible, help bridge it, she developed a year-long conversation – by phone and online – that engaged 12 people who voted for Clinton and 12 who voted for Trump. What she learned is not what she expected. Instead, as she says, “I learned a few things about our political climate today and a lot more about what it takes to live a fully connected life in our modern age.” In what follows, she tells this story and threads through it glimpses of her own and her family’s experience in China before coming to this country.

As many of us did, after the 2016 election Boting Zhang asked herself, “What’s a plebian to do?” I’m inspired by how quickly she responded. Since her childhood in China, Bo had carried in mind a dream of America as meiguo, the Beautiful Country. In late 2016, this dream from her childhood compelled her to leap into the polarized space that divides much of this nation. To try to understand the divide and, if possible, help bridge it, she developed a year-long conversation – by phone and online – that engaged 12 people who voted for Clinton and 12 who voted for Trump. What she learned is not what she expected. Instead, as she says, “I learned a few things about our political climate today and a lot more about what it takes to live a fully connected life in our modern age.” In what follows, she tells this story and threads through it glimpses of her own and her family’s experience in China before coming to this country.

Anne Focke

Destined for the Beautiful Country

I was born destined for the opportunity of America. As the only kid in daycare lucky enough to have parents studying in Meiguo – the Beautiful Country – I heard about it constantly. Meiguo sounded like an amazing place. I imagined Americans to be grinning all the time, just proud to belong to the nation that’s best at everything.

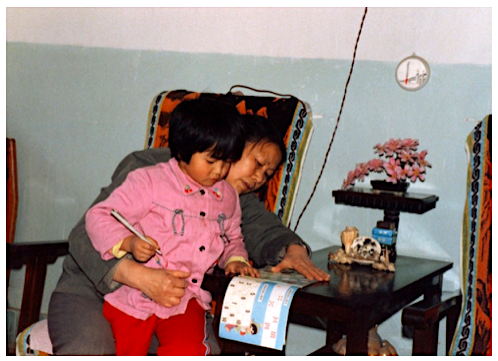

Months before my fifth birthday, my grandparents and I took the two-day train journey to Beijing. There, I boarded a plane alone for JFK. My parents would be waiting when the plane landed. I’d never see my grandmother again.

The American Dream tells us that success lives just on the other side of individual hard work and self-sufficiency. Three decades in, my family has lived that dream. But the proud and happy Americans that I’d expected to find on this side of the fairy tale? Turns out that we’re more complicated than that.

This is also a time when, around the world, cities and their surrounding countrysides find themselves at heated political odds. Many people seem resigned to the conclusion that their political opposites must be selfish, myopic idiots. Researchers and others have analyzed the causes of our political polarization, and I will neither rehash nor dispute these analyses. Our polarization has a complex history.

Through my year-long conversation I learned a few things about our political climate today and a lot more about what it takes to live a fully connected life in our modern age of individual ambition. My question about modern America now is this: How can we find the sense of belonging together that encourages people to work through their differences?

Between Americans1

Twenty-four voters from around the country participated in the year-long conversation online. Half had supported the woman I’d voted for; the other half had chosen the man I didn’t understand. Most participants were strangers to each other, but all were introduced to me by people I know.

At the start, the project was called “Into the Schism.” Then, in a fit of hope, I changed its name to “Between Americans.”

At this time in American history, it takes a lot of hope and trust for people to even come together. My hope was that the year-long conversation would encourage greater mutual understanding. For most participants, the experiment didn’t succeed in the way they, or I, had hoped. It succeeded in a totally different way.

Through mistakes that I made and through what participants shared with me at the end of the year, the project helped me see that political dialogue is hollow if it doesn’t address the creeping loneliness and floundering sense of purpose that lie under our nation’s polished surface.

America the lonely

Underneath a veneer of pearly-white smiles, modern Americans are lonely. Even a former Surgeon General, Vivek H. Murthy, has rung alarm bells about our epidemic of loneliness. He wrote, “The world is suffering from an epidemic of loneliness. If we cannot rebuild strong, authentic social connections, we will continue to splinter apart.” Although “loneliness” implies being alone, my conversations with participants surprised me by making it clear that busy Americans with lively social networks can also be intimately familiar with the feeling.

What’s more, this loneliness, this underlying stress to our collective whole, may be driven in no small part by our own restless individual aspirations for success. We’re industrious, ingenious, and interconnected, but these traits also lead to conditions that keep us apart: an extreme busyness, no room for serendipity, a craving for certainty and simple answers, and a crowded Internet.

Extreme busyness

The Between Americans conversation began in January 2017. Here’s what a few people wrote early in the project.

Immediately after the election, I felt like I needed to get more involved in the political process…. I kept coming back to the idea that I wanted to have a dialogue with people who think differently from myself.” — Participant A

I’ve never seen our country as polarized as it is right now. I don’t think that supporters of either major candidate in the last election are as blinkered as social media memes would suggest. One way to bridge the divide is conversation. So, let the conversation begin!” — Participant B

The project planned to use a combination of online writing and phone calls among small groups of participants. Almost immediately, participants and facilitators found themselves swept back into the urgency of everyday life. We only managed to schedule one small-group call with just five participants before everyone became too busy.

Yet, many participants didn’t lose interest. They still believed in the idea and wanted to continue – they just hadn’t expected to be so busy. This led me to wonder about the phenomenon of American busyness itself.

Our nation is home to two kinds of busyness. The first is a busyness of scarcity; many people are still working hard for survival in a nation of abundance. But graduating from scarcity often only brings Americans into a different busyness of abundance. The busyness of each participant seemed essential: responding to family needs or unexpected events in the context of overwhelmingly busy jobs. But in the aggregate, it formed a striking pattern. Something is wrong with our collective capacity for a functioning togetherness. This is a catastrophe that warrants deeper exploration.

To give you an idea of how hard modern Americans work, we forfeited 206 million vacation days in 2016. If an average worker works for 45 years, that’s over 12,500 lifetimes of paid leisure, thrown away in just one year.2

I certainly relate to busyness. Workaholism is in my DNA. My dad grew up in a farming community where poverty and hunger were well-known. Especially in the famine years of his childhood, the purpose and meaning of life was fairly straightforward: to survive, and to help others survive if you can.

Loneliness was impossible. It was an environment that could only be survived together. His community pooled resources to help my dad become their first college student, to leave poverty behind. After she and my dad moved to this country, my mom cleaned houses and packaged chicken eggs as the two of them worked their way through grad school in Connecticut. That is how, layer by layer, our family made its way into the American Dream.

The opportunities of reaching the Dream present an entirely different challenge: not to survive, but to remain fully connected in community. In the world of the American Dream, neighbors each have separate lawn mowers and kitchen stand mixers. Friends respect each other’s busyness and avoid asking for big favors. We buy insurance policies. We avoid surprises. The farther we move up in the social classes of the ever-less-burdened and more self-reliant, the harder it becomes to see our vital contributions to each other’s survival. But the less immediately necessary we feel, the more deeply we succumb to the stresses of uneasy belonging.

We humans go crazy in solitary confinement. We’re like single cells that shrivel up and wither away when separated from the larger organism of community. To the extent that humans have a baked-in desire beyond survival and sex, that desire is to belong together.

No room for serendipity

Shortly after college, I worked for two years in a guesthouse in a sparsely populated Japanese mountain village. My parents were bewildered at why I’d be so eager for the rural poverty that my elders had labored to leave behind. How to explain that I was enchanted by the serendipity of shared humanity that arises from moments of idleness and curiosity?

“Mornin’, Bo-chan!” I heard one early morning, faintly in the distance, as I picked my way downhill through the lingering darkness to our log-cabin office. My eyes searched the empty road and fields until I finally spotted our 76-year-old neighbor, cheerily hanging from the upper trunk of one of his Japanese cypresses, chainsaw in hand.

“Morning, Omo-san!” I yelled back.

“What are you up to today? More emails?” It seemed to always astonish him that there could be so many emails.

Later that day, he stopped by for a visit. Irritated by the interruption, I served tea anyway and paused for a long chat, having learned the hard way that busyness isn’t an acceptable excuse anywhere in this village, and certainly not for Omo. After all, he’s spent entire afternoons showing us how to better tend to our potatoes and eggplants.

Ten years later, these memories are bittersweet when I recognize that I don’t spare that kind of time or curiosity for strangers at home.

We’ve created this culture where there’s no spaciousness in people’s lives to energetically take time, reach out, connect, have community with people outside their immediate philosophical, political, socioeconomic groups.” — Participant E

In moments of spaciousness, people are almost reliably surprising. In busyness, people rarely are. Thread by thread, busyness tugs away at the serendipity of community until, collectively, we reach a threadbare state of diseased loneliness. Busyness crowds out surprise.

A craving for certainty and single answers

At the beginning of the Between Americans project, I’d imagined my facilitating role to be something like that of an engineer helping shape a river. I wanted to help the conversation land on the right balance of conflict and harmony—not so much conflict that the water becomes turbulent, not so much harmony that the water stagnates.

But it turns out that dialogue doesn’t need such careful physics. Dialogue simply requires the spaciousness of uncertainty and vulnerability.

One of the strongest personal characteristics that any person can have is the ability to be vulnerable. And it’s one of the things that I think as Americans we’re the worst at. We all put on this suit of armor that protects us. And when we talk about politics and community and growth and unity, those suits of armor actually protect us from solving the problems that we have. And I guess with my personal history of poverty as a child, and homelessness…that vulnerability and those experiences, those are strengths.” — Participant F

I once worked in an office where our leaders never agreed on anything. It was a running joke. But our team thrived on these disagreements. Unless something was on fire, we didn’t feel compelled to end every conversation with a resolution. Our disagreements forced us to reckon with the competing paradoxes of efficiency, quality, cost, creativity, relationships, and so forth. Difficult conversations challenged us to find a higher synthesis that could resolve competing needs.

But in the trap of political punditry, ideas are either right or wrong; there is no higher synthesis. When I buy into this trap, I fail to see the point of a conversation that won’t easily end in agreement or a meaningful insight. This also helps the schism grow.

I hate political discussions…. Even when someone sides on ‘your side’, it seems like they still argue with you on hair-splitting issues, just to be argumentative…. It almost makes me afraid to have an opinion on anything.” — Participant G

Communication lets us borrow each other’s brains so that we can think together. When politics becomes reduced to trading answers back and forth, we lose the full potential of dialogue. We each respond to conflict in our own ways, and each response can hold a piece of the truth. It’s in the very incompleteness of our individual truths that we can reach a wiser togetherness. Having all the answers would be terribly lonely.

By the end of the year, I was learning to be more comfortable with the honest unknowingness of true conversation. In that open space, the conversation made some progress. Along with uncomfortable moments, the river of dialogue began to find its natural flow. Participants shared some daring truths, displaying trust even if understanding was shaky. I was beginning to feel a larger kind of American belonging that I wasn’t finding anywhere else in the political landscape.

A crowded Internet

From the beginning, I knew that phone calls were different from online discussion, but I was surprised at how much more I connected with each Between Americans participant in hour-long telephone exit interviews than in the entire year-long online conversation.

A short excerpt from the online conversation earlier in the year was about environmental issues:

So I have posted some stuff that’s environmental. And there was actually a lot of thought that went behind that…. I would agonize over what I should post … like, what is something that I [can] talk about meaningfully, without getting too emotional to the point where I can’t talk about it anymore.” — Participant A

Referencing the same conversation in an exit interview, another woman reflected:

I remember there was one, that someone had written about the environment…. I saved part of the post in my notes and I got back to it later…. And I got a very thoughtful response back…. And then I dropped the ball – I think it was the Fourth of July – and I never wrote back. And I was like, ‘Damn … I lost an opportunity to really keep this conversation going and learn about something that I don’t know a lot about.’” — Participant I

Before these phone calls, I’d forgotten how much of our human complexity remains below the surface of the Internet. When we type, our backspaces and pauses – the vulnerable hesitations that connect us as humans – disappear as unwritten words. And what’s more, the Internet often acts like a crowd, and crowds carry their own distortion.

At the start of the Cultural Revolution, when my mom was 11 years old, she watched from a crowded plaza as student leaders on the stage kicked, hit, and bit her dad’s colleagues in order to force public confessions of academic privilege and oppression. The crowd chanted slogans in support of class struggle.

When my grandfather took his own turn on stage, my mom slipped away from the square. She avoided future “struggle sessions.” Away from the crowd, she got used to feeling alone. Only decades later did she begin to hear how uncomfortable others had also been in these public meetings.

What my mom saw – the people, the emotions, the chants – had been real. As she witnessed, crowds readily amplify extremism. This is the landscape of mass communication. Not only can written conversations filter away our humanity, but the crowded Internet also suffers under the simplifying distortions of crowds. When we forget the limitations of the Internet terrain, when we allow it to draw our attention away from the real people right next to us, we filter out our true complexity, and our loneliness grows. When I forget that we are deeper than the Internet, I conclude, wrongly, that everyone has gone crazy.

Beneath partisan politics

Between Americans was started as a way to understand and perhaps help bridge the polarization that was so apparent in the 2016 election. What I found instead, beneath partisan politics, is a shared struggle to be fully seen through the haze of each other’s busyness, ready answers, and hyper-connected networks. In my exit interviews especially, I glimpsed a tender layer of our nation that wants to know itself better, but that feels stuck, stuck in our polarization. It’s lonely and frustrating to be in a conversation that’s stuck, and yet, we Americans have together created a polarized, disconnected outcome that few of us want..

In Tribe: On homecoming and belonging, Sebastian Junger writes, “Humans don’t mind hardship, in fact they thrive on it; what they mind is not feeling necessary.” Modern ideals of self-sufficiency have gone a little too far.

In this modern world of bewildered belonging, political warfare offers a rare gift – an experience of shared purpose with other people. As Junger also says, in addition to all its destruction, “war inspires ancient human virtues of courage, loyalty, and selflessness that can be utterly intoxicating to the people who experience them.”

But belonging is a heavy load for politics to carry. Political conversations often echo strains of an exasperated belonging that can’t be solved through politics.

I think we’re actually damaging the structure that allows people to be individuals, because now they have to associate with these labels. Are you a Republican or a Democrat? Are you a feminist or not a feminist? And they don’t even come close to touching on the complexity of the actual human…. I think this creates a sense of isolation and loneliness because here you can name all these containers, but you’re not really known. Nobody actually really knows you.” — Participant N

As our democracy matures, the very qualities that brought us this close to success – our busyness, our conviction, our production-line innovations – could be the very things that hinder us from moving forward.

Looking back from the future, I hope we’ll see this time in history not as a struggle between competing ideologies, but rather as an awakening to the complexity of our problems and a gradual rejection of ideological answers. Generative, inclusive disagreement isn’t something we need to remember how to do. It’s something we’re learning for the very first time.

My conviction for bridging divides is not about finding peace and harmony, or even common ground. Rather, I believe in talking more so that we can begin to become, perhaps for the first time in American history since colonization, a whole that’s truly greater than the sum of our parts.

Boting Zhang works at The Bramble Project, “joyful and conscientious urban development.” Of her work she says, “I work to support collective wisdom and agency in the complex civic and social dynamics surrounding urban change and belonging. I offer ideas for how our polarized society can heal itself in a parallel essay, ‘Our Political Polarization: Heartbreak and healing,’ on the Bramble Project blog.”

Boting Zhang works at The Bramble Project, “joyful and conscientious urban development.” Of her work she says, “I work to support collective wisdom and agency in the complex civic and social dynamics surrounding urban change and belonging. I offer ideas for how our polarized society can heal itself in a parallel essay, ‘Our Political Polarization: Heartbreak and healing,’ on the Bramble Project blog.”

References

- Between Americans began as a commitment to remember how the 2016 election felt. Since art is the only way I could think of to record an emotional time capsule, I committed to an art piece about that election night. My commitment was a seed that grew into this year-long conversation. To see and hear the full art piece telling the story of the year’s project, please go to: Between Americans Timeline. I invented the format you’ll see as a way to display the conversation. Among other things, it includes about three hours of audio. Scroll to the bottom of the page for links if you’d rather listen to it as a podcast.

- “Being busy can make you rich, but being rich makes you feel busier still.” The Economist, “Why is everyone so busy?”December 20, 2014.

![]()

1 Comment