In December last year (2021), an essay I wrote, “Collectively Imagining a More Just World,” was published by the Polity of Literature on ArtsEverywhere.com. The editor’s introduction and the first few pages of the essay itself are included below. On the essay’s title page, the Polity of Literature offers this brief summary:

Travis Ray ComesLast committed a terrible crime, but what should happen next? Stories of injury and stories of repair involve us all. We must tell and receive these stories collectively.

The commission to write the essay gave me the freedom to follow the story wherever it took me, and the pandemic gave me time. The story takes a winding path with many side trips along the way as it follows two main characters who were also my principal collaborators in learning and writing. Their words are often incorporated directly.

Travis Ray ComesLast, Assiniboine-Hunkpapa and Lakota Sioux, has been in prison since he was twenty and so far has served twenty-five years of a fifty-one year sentence. He’s no longer the person he was when he entered prison. Recently he wrote, “Changing my life is a way of showing remorse, taking responsibility, and making amends.”

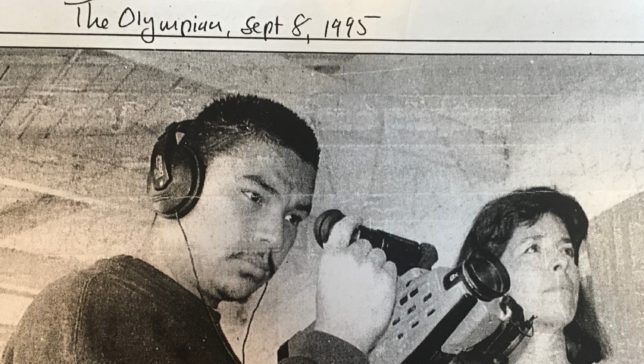

Heather Dew Oaksen is a filmmaker who has known Travis since 1994 when she taught video skills at Green Hill School, a maximum security juvenile detention center. Their friendship has continued and grown since then. Heather spearheads a team of supporters who are fighting for Travis’s freedom.

Above all, Travis’s trust was fundamental to my ability to tell this story, and Heather’s high spirits and willingness to engage in the nitty gritty details were essential.

My third main collaborator, Polity of Literature editor Matthew Stadler, offered me the opportunity to write, engaged with me in the ideas I took on, and showed me in new ways that writing and reading are fundamentally a collective process. I encourage you to check out both the Polity of Literature series and the ArtsEverywhere site.

The introduction and first section of “Collectively Imagining a More Just World” follow. The full essay is here.

Anne Focke

Travis Ray ComesLast, an Assiniboine-Hunkpapa and Lakota Sioux tribal member, grew up near Spokane, Washington. After a chaotic childhood he committed a series of increasingly serious crimes, later explaining to a friend, “I got into as much trouble as possible one day trying to get arrested ’cause I knew that if I did I would get help, and since I didn’t know how to ask for help, that was my way to get help.”

By the time he was an adult a conviction for killing a man had put him in the Washington state prison system for more than fifty years. He would live and possibly die as a prisoner. The system that put him there, the state justice system, cast his imprisonment as compensation for the horrible injury he caused his victim and his victim’s family—a-life-for-a-life being the logical conclusion of a system predicated on an-eye-for-an-eye. Now Travis is forty-five-years old. The victim’s family is still aggrieved; the daughter who never had a father growing up is living with the life-long impact of that loss. And Travis, an entirely changed man in his head and heart, will live most of his life, perhaps even die, as a prisoner.

In the 1990s Travis told his story to a young filmmaker, Heather Dew Oaksen. Over the next decade Oaksen began telling Travis’ story, and the stories of other prisoners, through her films. Anne Focke, in her second piece for the Polity of Literature series, tells the story she learned from Heather’s films and from Travis himself after she joined a team of supporters Oaksen gathered to help Travis in his effort to regain his freedom.

Whose story is this? How should it be told, and by whom? Literature is collective, always. It exists only among writers and readers and never in solitude. Literature displaces solitude by bringing us into the collective space of writing and reading. As such, it is a powerful means for justice, which like its inverse, injustice, is always and only a collective condition.

![]()

Ecosystems are so similar to human societies—they’re built on relationships. The stronger those are, the more resilient the system. And since our world’s systems are composed of individual organisms, they have the capacity to change. We creatures adapt, our genes evolve, and we can learn from experience. A system is ever changing because its parts—the trees and fungi and people—are constantly responding to one another and to the environment. Our success in coevolution—our success as a productive society—is only as good as the strength of these bonds with other individuals and species. Out of the resulting adaptation and evolution emerge behaviors that help us survive, grow, and thrive.

— Suzanne Simard in The Mother Tree

This story is not about forests directly, but it benefits from what we, in human societies, can learn from forests. As I write, I want to learn how or whether the many related but disparate people and activities I come across can work together toward something new and larger. Can they become like healthy soil, with mycelia, fungi, mycorrhizal networks, tree rootlets, all feeding and influencing each other? How does this mesh grow thicker and stronger? How can it become visible and, over time, undo or take apart and break down large, seemingly permanent structures and institutions and then grow new ones, like fungal fruiting bodies, to provide nutrition to new or ancient seedlings? New narratives will be needed for this and perhaps are already being created by collectively imagining new futures.

My story begins with a single thread, a single path through the ecosystem of the story. I start with one individual, Travis Ray ComesLast.

![]()

Hey Heather,

I came across an article in the Spokesman Review by Colin Tiernan… it was a story entitled “All These Children Matter”…actually made front page! It was a story about the unmarked graves of the children found at some boarding schools and the affects it has had on Native Peoples. It spoke about intergenerational-trauma, PTSD and secondary PTSD resulting from the atrocities experienced at the schools. Reading the stories made me cry… its sad and frustrating!

I couldn’t help but remember all the stories my mom would tell me of her experience at boarding school and the thought of how much the affects had on my upbringing? I wonder what if she would of felt safe enough to teach me and my siblings our traditional ways and language… would I of made better choices, did the trauma [she] experienced at boarding school deprive me of a fair equal opportunity at life? How many and to what extent did the boarding school traumas have on Native Americans? Experts say the trauma has been passed on from generation to generation, even to the extent its in our DNA!! Had my mom not attended boarding school would I be in prison??

I just know much of what keeps me in place today and made me the man I am today is the traditional ways of my people. The story shed some light on what Indians have been saying… it validates what we been knowing all along! I encourage you to read the article.

An email sent by Travis Ray ComesLast from Airway Heights Corrections Center, to a friend, Heather Dew Oaksen, August 2021

![]()

Travis Ray ComesLast, Assiniboine-Hunkpapa and Lakota Sioux, is in his twenty-fifth year of incarceration for a murder committed when he had just turned twenty. He will be seventy-four when he finally completes his court-mandated sentence of fifty-one years. Born in 1976 in Spokane Washington, Travis speaks of himself as having felt abandoned as a child, reports Heather Dew Oaksen, a friend of mine as well as Travis’. He grew up in the midst of constant disruption and violence. His father was in prison and his mother mostly absent. An alcoholic for most of her life, his mother, Sharon, would disappear for long stretches of time.

Travis has three siblings, Heather told me, and so many half-siblings she lost track of the number. “I never really knew my biological father,” Travis told her years later. “He was in and out of prison all my life! My earliest memories with him are all bad… giving me beer in the little half beer cans they use to sell, hitting my mom, and going on a high-speed chase with him and my uncles. In the middle of the chase, they dropped me off on the side of the street and told me to go home… dirt was all around me from the car racing down a side road. Asking my mom about this years later she said I wasn’t even two years of age when it happened.”

The extended family is large and sprawling—a stepfather, the stepfather’s brother, aunts and uncles, and many other familial and tribal connections in the Spokane area. What I know of Travis’ early years are the stories he tells. Others have surely had similar childhoods, even if I have not. I repeat the stories that Travis tells because I want to show him as he sees himself. As a five-year-old, an aunt took Travis in and cared for him at her home, which she also ran as a house of prostitution. Travis made easy friends with “all the ladies,” and at some point, they gave him a few quarters for candy. When the news of this exchange got around, the ruling pimp exploded in anger and fired gunshots at the closet where Travis was hiding. Even in this near-parentless context, Heather said, as Travis got older, he followed his aunt’s example and was constantly trying to take care of his younger siblings and his mom. At about age 17, after his three siblings were taken in by relatives, he was left alone in a house with no electricity. “I spiraled out of control after this,” he said. “I got into as much trouble as possible one day trying to get arrested cause I knew that if I did, I would get help, and since I didn’t know how to ask for help, that was my way to get help.”

This family life had a lasting impact that shows in the lives of Travis and his siblings today. A younger brother, Kenneth, is in prison for a double murder he committed at age 15. While an older brother is doing pretty well, his sister suffers from addiction and has multiple children by different fathers. Most of his half-siblings are in jail. “There is much history in the ComesLast name,” Heather told me recently, “and it continues to hold Travis back.”

Even while living in this home environment, Travis learned of his Indigenous culture and was proud of his Sioux heritage. He’d been taught by his stepdad and that side of the family—grandparents, uncles, aunts, cousins, and friends of the family. They had a drum group called Spokane Falls and travelled around the area performing. He said recently that what he knew of his culture he learned through the drum and singing and dancing. From age eight to thirteen, this kept him out of trouble. He even had his own regalia. At one point, though, the family gave away the drum and all the regalia, collected over years from various relatives. This had a terrible impact. “It changed the dynamic of the family,” Travis said. The family lost its centre, and he began his own downward spiral. Speaking to Heather in a juvenile prison, he told her: “There’s a lot of things I still don’t know about my culture. You know, I feel something in my life is being left out. I don’t feel whole. Until I know fully about my culture and all my ways, that piece of me will always be missing.”

Recently, Travis had a heart-to-heart with his mother about her boarding school experience. He wondered why she waited so long to tell her children the story. She had been reluctant to talk about it earlier, he told Heather. She wanted to forget. Her response is understandable. Stories of the abusive system of Indian Boarding Schools have filled the news over the past year or so. In 2020, the Washington State Senate adopted Resolution 8703, which acknowledges the government’s role in the abuse of Indigenous children at state-funded boarding schools. “This is part of our lives that just won’t go away,” said Tulalip tribal member John McCoy, a retired Washington state senator. McCoy went on to explain that the resolution states that between 1869 and the 1960s children at these schools “were punished for speaking their native language, banned from acting in any way that might be seen as representing traditional or cultural practices, shorn of their hair, stripped of traditional clothing and all things and behaviors reflective of their native culture, and shamed for being Native American.” The National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition, begun in 2012 and based in Minneapolis, is launching a ten-year push toward healing, education, and advocacy. Their website quotes board member Sarah Eagle Heart saying, “Our grandmothers are just now talking about the pain they experienced in Indian Boarding Schools.” Travis’ mother is one of these grandmothers and just wanted to put the experience behind her.

![]()

The full essay is here, “Collectively Imagining a More Just World.”

![]()