Apparently, you become an institution simply by surviving, by being there. — Edit DeAk

In mid-1974, before I knew many people in that city, I made a trip to New York. One of the few New Yorkers I knew beforehand thought I should I meet Edit DeAk and suggested I go to a party in her loft. My friend had been invited but couldn’t go and assured me it would be OK. So I went alone.

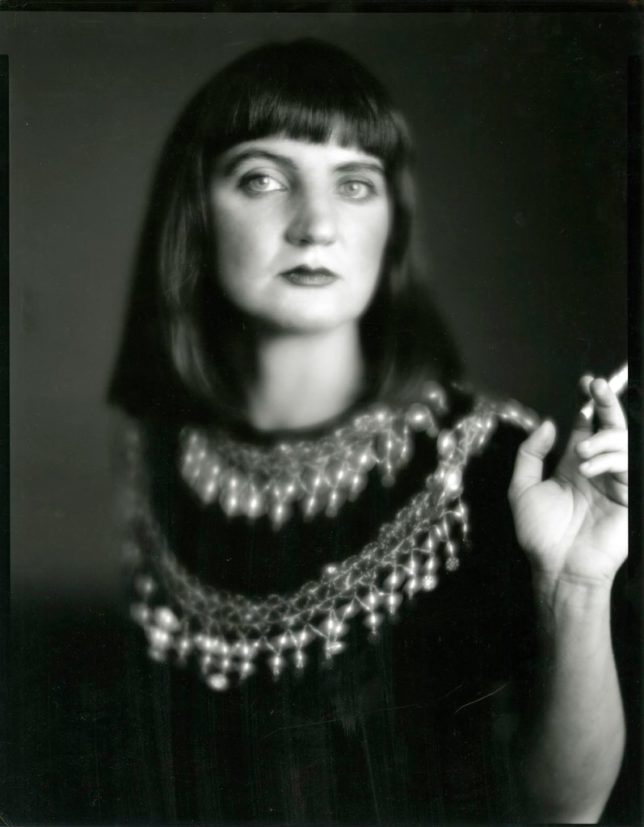

DeAk’s loft was on Wooster Street above the Paula Cooper Gallery, up several long flights of stairs. Although I arrived to find the loft crowded with people, I received what struck me as a surprisingly open and friendly welcome. Meeting DeAk in her loft that evening began a periodic bi-coastal friendship and introduced me to a vibrant New York art world I hadn’t known before. Among other things, I became a dedicated subscriber to Art-Rite, a journal DeAk had co-founded a year earlier as an alternative to established art magazines of the day. Though DeAk and I lost track of each other over the years, her 2017 obituary in the New York Times threw me back to those days and reignited my interest in her.

Edit DeAk was born in Budapest in 1948, fled Communist Hungary in 1968 in the trunk of a car, and went almost directly to Manhattan to leap into the art world. And leap she did. William Grimes, who wrote the NYT obituary, called her “the doyenne of a downtown New York art world that was a playground for many a nascent movement and ideology.”

One of the most satisfying finds in my search for stories about her was an engaging essay by David Frankel, “On Art-Rite Magazine,” published by 032c magazine in 2005. Frankel recalled that he met DeAk in 1981 when he was newly on the staff of Artforum. “Edit regularly danced by [to see then-editor Ingrid Sischy]. She would hurry through the office, laughing, vivid, bright-clothed, Hungarian, making herself briefly focal…” He added that while she was “intimidatingly glamorous,” he was “struck by her generosity and by an endearing modesty that runs through her general flamboyance.” No doubt this generosity is what I felt in that loft when I first met her.

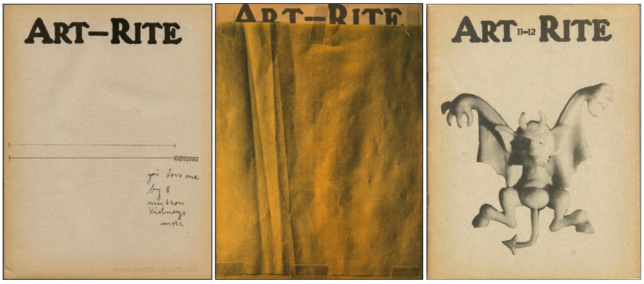

DeAk founded Art-Rite with two fellow Columbia University students, Walter Robinson and Joshua Cohn. Its goal was to provide “coverage of the undercovered,” to focus on art at the margins: performance art, video art, conceptual art, and outsider art. The magazine was written, edited, designed, typeset, published, and distributed out of DeAk’s and Robinson’s downtown lofts between 1973 and 1978.

Frankel’s essay began with a 1974 quote from DeAk about the beginnings of Art-Rite:

We were riding on the absurdity of the situation—that we were three nobodies, had no money, had no fame, and didn’t know anybody in the art world. But it was perfect—we were totally free.

The magazine’s design, reported Frankel, was “stylish and plain at the same time.” It was printed on newsprint in the editors’ belief that the low-cost process would help deinstitutionalize and demystify the esoterica it contained. In its time, wrote Frankel, Art-Rite “must have been startling in its colloquial informality.”

“An important aspect of Art-Rite,” said DeAk in her interview with Frankel, “was a whole new tone and attitude. It was unheard of to have a sense of humor at the time, or not to be talking about ‘the problem’ of art – the problem of this, the problem of that.”

Discovering these stories helped me understand why I felt such a kinship with DeAk in a way I didn’t put into words at the time. It wasn’t her glamorous side, and I lived too far away to be part of the downtown New York art scene around her. As I read, I found phrases that helped explain the connection I’d felt – Frankel’s term “colloquial informality,” his description of Art-Rite as open and democratic, her own words describing the journal as “a restless but friendly, constantly evolving entity,” and especially her desire to “deinstitutionalize” the magazine.

![]()

Shortly before I met DeAk and about a year after the first issue of Art-Rite was published, I was one of a group of artists who started an artist space in Seattle. We named it and/or. Rather like Art-Rite, and/or “presented the underpresented” – artists whose work included video, installations, performance, new music, conceptual art, and art writing. We hosted artists, curators, composers, and writers from our region and beyond, DeAk among them. Knowing of and/or may have been part of the reason our mutual friend thought DeAk and I should meet.

As and/or developed, I regularly worried about the dangers and impact of becoming an “institution.” It felt sort of like a dirty word. In 1975, I wrote:

One of the greatest challenges is working with an ongoing form; the “trick” is not simply to make an organization that perpetuates itself, but to make one with life, challenges, risks, and new ideas… balanced between giving enough structure, stability/credibility to assure a continued existence, and giving enough openness, flexibility, free-ness to allow for real growth, surprise, significant work and change.

This worry once came up in a conversation with DeAk, perhaps during her visit to Seattle. We talked about our respective organizations, and her words stay with me still. Though she was barely managing to keep Art-Riteafloat, within just three years she was starting to hear people refer to Art-Riteas an institution. “Apparently you become an institution simply by surviving, by being there,” she said.

![]()

As it turned out Art-Rite didn’t survive long, if “survival” is understood in conventional terms. It folded after only five years. and/or lasted longer, but we closed its core operations after ten years.

Lately my thinking about the challenge of balancing risk and openness with continuity and stability has gotten more complicated. I know there’s a place for reliable, slow-moving, barely-changing institutions designed for the ages. There’s also a place for organizations that develop lighter-weight, flexible structures but with enough focus on management systems that they can last through many ups and downs, though maybe not forever. But there’s also a vital place for organized collections of people who stay together for a while, who direct all their energy and resources to taking a particular action or accomplishing a specific mission in response to immediate circumstances, and then just go away.

About twenty years after and/or closed, I was invited to talk about it in a discussion of birth and death. To prepare, I wrote these observations:

and/or was not built to last, profoundly not.

Its energy went to doing, not to building a lasting structure.

In the end, it divided, seeded, dissolved its center.

It was allowed to become “myth,” to have a beginning and an end.

In my imagination, closing and/or would release the energy of its community and of the artists involved, allowing the energy to take new forms and pop up elsewhere.

According to the reports I read, Art-Rite went through a similar metamorphosis. After the magazine folded in 1978, DeAk’s spirit and energy did not slow down and, at least for a while, showed up in other places. As an art critic, she contributed to Artforum, Interview, ZG, and other art publications. Trey Speegle, in a WOW Report column announcing her death, noted that she continued to be “a downtown fixture in the 80s NYC art scene that loved and revered her.” Gallerist Massimo Audiello began his own remembrance by writing, “Downtown NYC is in TEARS!!! One of our most shining minds is gone.”

Even though her health sidelined her for the last two decades of her life, her impact and her spirit continued on in people who knew her. Speegle wrapped up his column with this:

She really was one of those vital sorts who introduced, connected, inspired, and informed. She was a creative conduit. I’m still kind of not believing she’s not going to post some poetic comment on Facebook and say, “Hey, I’m not there now, I’m here.”

I think again about DeAk’s words – “Apparently, you become an institution simply by surviving, by being there” – and I want to play with them. How about this: “Apparently, survival isn’t simply about being an institution, it’s about being there.”

What endures doesn’t have to be as tangible as brick and terracotta or metal and steel. Myths and memories of individual and collective activity may seem ephemeral, but they can have a tensile strength that lasts. Even long buried and apparently forgotten, they can pop up again to be rediscovered, to again inspire something new.

![]()

References

“Edit DeAk, a champion of outsider art, dies at 68,” William Grimes, The New York Times, June 22, 2017.

“On Art-Rite Magazine: An analysis of Art-Rite magazine and its history,” by David Frankel, 032c magazine, Issue #9 (summer 2005), retrieved from the Internet Archive: Wayback Machine,

“#RIP: Art Critic, Edit DeAk,” Trey Speegle, The WOW Report (World of Wonder), June 9, 2017.

For more on and/or see: “and/or – enough structure and enough openness” and “goodnight and/or a wake.”

![]()