“Well, I guess that one was all wrong, wasn’t it.”

When I was a kid, it seemed like my dad had to go out of town for work every other week. I remember trooping off with my mom and four younger brothers to the San Diego airport to see him off. We’d all stand with our noses to the chain link fence, facing the wind from the propellers as Dad’s plane took off.

Other than knowing that he worked as a physicist who studied sound traveling under water and through the earth, I knew very little about the work that took him away so often. As kids we knew that Dad worked for the military in Washington D.C during the second world war, and we knew that throughout his career with the military he remained a civilian and a scientist. We also learned that he studied explosions (sometimes up close) and that he had something to do with “top secret” projects, including one, we found out later, to test an underwater nuclear explosion in the early 1950s. It’s curious to me now that, back then, I just accepted the secrecy surrounding his work and didn’t feel compelled to learn any more details about it.

Instead, what I remember most about my dad the scientist was the time he spent with us answering our questions and describing how things worked – what the seismograph in the corner of the dining room did, how a polaroid camera worked, how molecules and atoms were like worlds within worlds, and what forces held them all together. He was our own “Mr. Wizard” at the dinner table.1 He loved the process of science – coming up with a theory, testing it, finding it doesn’t work, trying another, maybe another and another, and in time finding the one that’s true. And he got special joy in seeing that click of discovery in our faces when we understood whatever he was explaining at that moment.

Another thing we knew about our dad was that he’d met Albert Einstein. The proof we had was a photograph that I’ve carried in mind since I first saw it. My brother Karl, the one of us who took after Dad and became a physicist, recently tracked down and annotated a copy of the photo for me. Taken in 1931 at Caltech where Dad got his doctorate and where Einstein was an occasional visiting professor, the picture shows a large group of faculty and grad students surrounding Einstein, the unmistakable focus of attention in the center of the front row. Also unmistakable to us was our dad in the third row right behind Einstein.

![]()

In 1959, the year I started high school, Dad accepted a position as chair of the Physics department of the then-new Harvey Mudd College. He told me he could no longer work under conditions where top military brass had the final word over technical work, regardless of their scientific knowledge. He stayed with the college until he retired in 1971 and remained active as emeritus professor until he died in 1986.

Recently, another brother, Ted, gave me a transcript of a long interview with Dad. Ted and his wife Vicki are the unofficial historians for our family. Part of a larger project titled, “Harvey Mudd College Oral History Project on the Atomic Age,” the interview was conducted in 1975 by Harvey Mudd and the Claremont Graduate School.2

At the first opportunity, I read all 167 pages of the interview. Not only did I learn more about Dad’s once “top secret” past – hinted at on the first page with a notice, “This manuscript is authorized as ‘open’” – I discovered there was more to the story of Dad and Einstein than just the gathering at Caltech.

Two-thirds of the way into the manuscript, the interviewer asked, “Al, you said you had an additional anecdote to tell about Einstein and the explosion work you had done earlier.” Dad described a time he and a colleague were sent to visit Einstein in his office at Princeton. They spent the better part of the day with him, Dad said. “We met him in the morning, had lunch with him, spent two or three hours in the afternoon, then went back to Washington.”

The interviewer asked, “How was he to converse with?”

Oh, very pleasant. Very easy, no problems. He was a remarkable person. Very retiring. To meet him on the street or talk with him, you wouldn’t have thought of him as someone with the mental power of an Einstein. He was gregarious and very much concerned with social problems, religious problems. He was really a very deeply religious person…sincerely in communication with his creator.

The interviewer then asked, “Why were you sent to meet with Einstein?”

The people at the David Taylor Model Basin [site of much of Dad’s explosion research] brought to my attention the fact that the Bureau of Ships had asked Dr. Einstein to develop a theory of ship damage resulting from non-contact underwater explosions. One of the basic principles that he used to develop his theory was the assumption that steel, under the sudden impact of a shock wave, would break in brittle fracture. Just the way glass breaks.

Now I had some data that indicated this was not strictly true. So the Bureau of Ships asked Dr. Hartmann and me to go out to Princeton and interview Dr. Einstein and give him the information we had.

So we made the trip on the 2nd of August, 1943. This was a very hot day and Einstein greeted us very pleasantly in his office, but he looked awfully hot. If you are familiar with Dr. Einstein’s pictures, there is a halo of white hair around his head, and on this particular day there was no halo. The hair was sticky with sweat and curling around his ears and around the back of his neck. He looked like a very hot and uncomfortable person.

He proceeded to tell us about his theory, and he had worked it out on a blackboard which was right behind his desk. Then, after showing it to us, he asked what the information was that we had. We had brought along some photographs of a bomb in the process of detonation. These were photographs taken at very high speed with a movie camera, and the first two or three frames showed the bomb case expanding like a rubber balloon. Now this is anything but brittle fracture.

Dr. Einstein took one look at that set of photographs and turned around and rubbed off his theory. [Laughter] He said, “Well, I guess that one was all wrong, wasn’t it. Now let’s see what we can do.” And in the process of the next five minutes, he worked out a completely new theory developing it right there on the blackboard, using the deformation of steel at first, followed by brittle fracture, which does occur.

I thought that this was one of the best examples that I have ever heard of the ability of a man, who is truly great, to say, “My theory is no good, I’ve got to start over again,” when someone brings up a fact that is contrary to the theory. Somehow, sure, Einstein is always accepted as a great man because he developed this theory and that. But to think of his ability to just scratch it, wipe the slate clean, and start over again is something that you rarely have an opportunity to see.

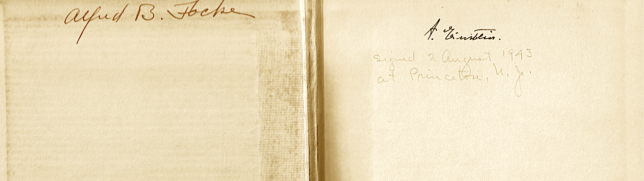

My brother Karl added a footnote to this story. Apparently, when Dad went to Princeton that day, he took a copy of Einstein’s textbook. After showing that Einstein’s theory was wrong, Dad asked him to sign the book, as if to honor true greatness, “See, your theory is wrong. Can I have your autograph?” The textbook is on Karl’s bookshelf.

![]()

It’s not just scientists who need the ability to say, “Oops, I’d better scratch out that idea and try again.” Can we non-scientists cultivate a similar capacity? Are we willing to shift our views given new circumstances and insights that cast doubt on our theories? The proof of error in our social, economic, and political ideas is seldom as clear-cut as a photograph demonstrating that steel can expand like a balloon. Though more difficult, the ability to acknowledge our errors or misconceptions and make adjustments in our social and political ideas is just as crucial as is the ability to change our scientific theories.

I constantly have to fight a stubborn streak in myself that wants to be right, even when I should probably question it. And that stubbornness is not the way I like to see myself. I want to be open to hearing different, even contradictory information and being flexible enough to revise my ideas and my action. Perhaps I need to cultivate my dad’s sense of delight at the click of discovery – even if the discovery is that I’m wrong – and remember Einstein’s words: “Well, I guess that one was all wrong, wasn’t it. Now, let’s see what we can do.”

“Now let’s see what we can do.”

![]()

Notes

- Watch Mr. Wizard was a TV program for children demonstrating the science behind ordinary things (1951–1965).

- The oral history interview was recorded on three different days. This excerpt begins on page 112 of the manuscript, at the beginning of the third day, March 14, 1975. The interviewers were Enid H. Douglass, director Oral History Program, Claremont Graduate School, and John B. Rae, Professor of history, emeritus, Harvey Mudd College of Engineering.

![]()