What becomes history is to some degree determined by what is archived.

These words by artist, curator, and editor Julie Ault are quoted in a description of Field Histories, a series of essays highlighting the value of archives that begins publication this fall. Common Field, a national network of artist-centered spaces and organizers, is commissioning Field Histories to encourage its members to become aware of the value of their archives and to think creatively about the preservation of the materials.

The series has been championed by Martha Wilson – Common Field board member, artist, and founder of Franklin Furnace, a 42-year-old example of an artist-centered space…and a sterling example at that. In her description of Field Histories, Martha observes that, especially when arts spaces blur the lines between disciplines – as in performance art, video, and installation art – the preservation of archival materials can be especially challenging, and when the spaces themselves represent a rebellion against institutionalization, preservation of archives is often a low priority. While acknowledging that “the critical value of archives to historians’ original research is well established,” in the end she says, “We fear that the archives of some art spaces have wound up in dumpsters and are lost forever to art history.” She and Common Field hope these essays can help prevent filling more dumpsters this way in the future.

I’m pleased to be commissioned to write a piece about the archives of and/or, an artist space that operated in Seattle from 1974-1984. Because and/or lived and died in a far off corner of the country before the internet came of age and few Common Field members are likely to know of it, I feel obliged to share a bit of and/or‘s history along with stories of its archives. The resulting essay follows here and is being published simultaneously on Common Field’s website as the inaugural essay in the Field Histories series.

– Anne Focke

![]()

goodnight and/or a wake

An incomplete story of one organization’s archives

Once upon a time we thought we’d put it safely to bed and that we’d freed it to fly into legend. But, then, 30 years later it started stirring . . . awake.

![]()

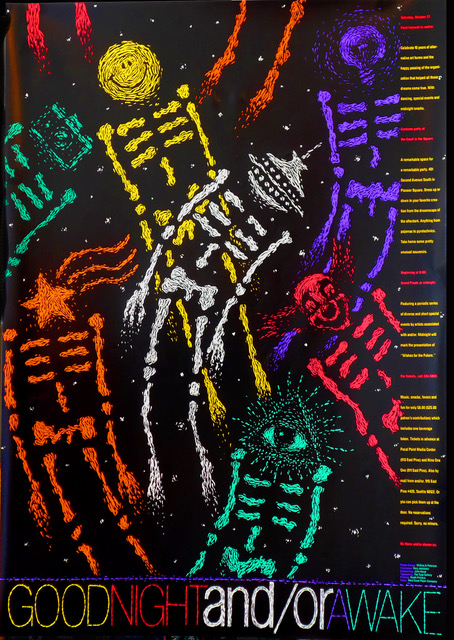

On Halloween 1984, and/or, a ten-year-old artist space, hosted a costume party in the historic Pioneer Square neighborhood of Seattle – “GOODNIGHT and/or A WAKE.” With this party, the organization whose name begged to be completed with another word (some tried and/or “gallery,” others added “studio” or “workshop”), completed its run and closed down. The time had come to make space for other things and to let and/or move into memory.

As part of closing, plans were made to allow and/or’s major programs to spin off as separate entities. Its central spaces were cleaned and vacated, and its files were all boxed up. An artist friend of and/or, Buster Simpson, agreed to let us store all those boxes – about 50 of them – in his studio at the Pike Place Market. In a matter of months, however, he had to relocate and had no room in his new studio for our boxes. Norie Sato, an artist and and/or staff member, and I managed to find space in an empty ballroom a few blocks away, though it, too, was a temporary solution, as the building was destined for demolition.

Norie and I couldn’t imagine continuing to drag 50 boxes of mostly paper from one location to another, but we also couldn’t face the idea of just throwing them away (and in 1985 recycling wasn’t an option). I can’t remember how we got the idea of donating them to a library or how we made the connection with Special Collections at the University of Washington Libraries. But we offered the boxes to them, and they took them all, as is. All, that is, except a few that I held back, thinking they might be handy to have easily available. I could manage to store about ten.

From what I know now, I suspect a transaction like this would be handled very differently today. Special Collections would probably be much fussier about what they accept, and I would certainly be a more knowledgeable donor.

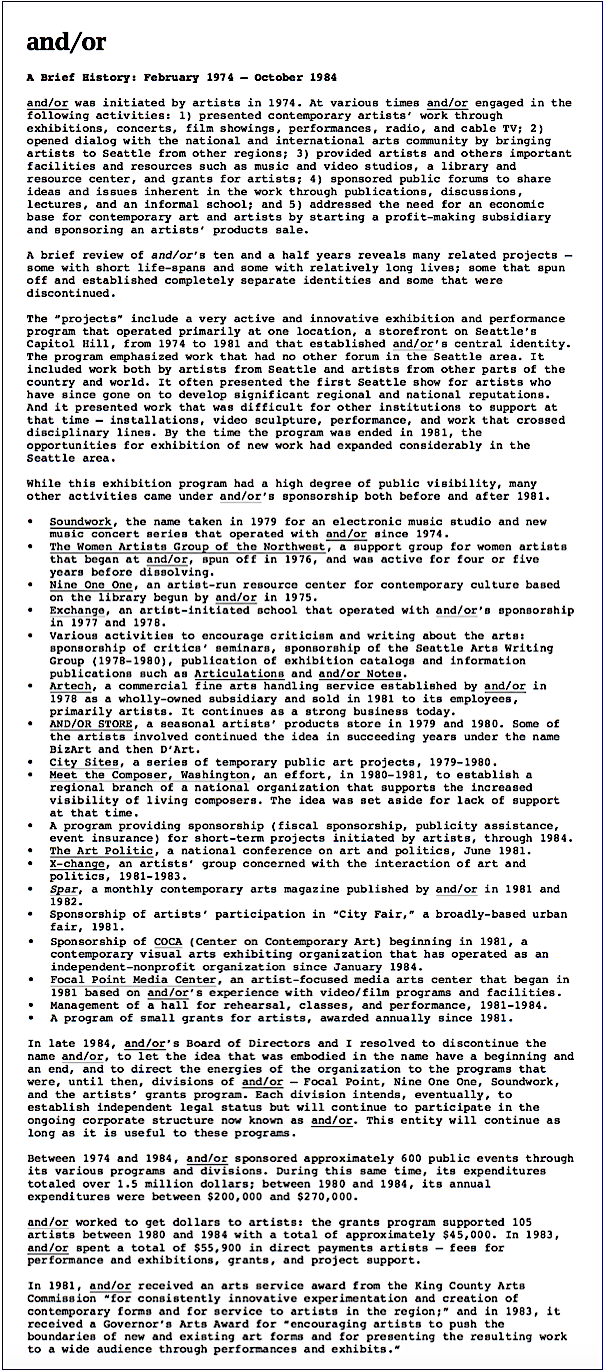

But . . . what the heck was and/or? And why worry about finding a home for its many boxes of files? Rather than write a new summary of its history, I defer to a report written by a 34-year-younger me a few months before and/or closed. It is presented here in a font rather like the one on my typewriter back then, and I underlined the name because my typewriter didn’t come with an italic font.

![]()

![]()

This history doesn’t give a picture of the actual art that swirled around and through the place – of what it looked or sounded like. One way to fill out the story is to glance through an accompanying list of the individuals and groups whose work was presented by and/or – visual artists, composers, videomakers, performers, writers, sculptors, filmmakers, photographers, curators, musicians, playwrights, performance artists, poets, among others. Even with 807 names, the list is incomplete. After it was distributed, we heard from people we’d missed.

Here are just the “A’s” – Keith Abbott, Vito Acconci, Kathy Acker, Acme Composer Performers, Paul Ackerman, Ibby Acosta, John Luther Adams, Cathy Aldworth, Jody Aliesan, Jo Harvey Allen, Penny Allen, Terry Allen, Jerri Allyn, Jim Allyn, Max Almy, Renate Altenrath, Beth Anderson, Denise Anderson, Eric Anderson, John Anderson, Mark Anderson, Laurie Anderson, Rob Angus, Ant Farm, Sharon Anthony, David Antin, Eleanor Antin, Jacki Apple, Evan Aresvir, Trisha Arlin, Ed Armstrong, Christoper Arpin, Mary Ashley, Robert Ashley, Sam Ashley, Asian Exclusion Act, Dana Atchley, Daina Augaitis, Natalie Auger, Diana Aurigemma, John Aylward, Alice Aycock, Mary Avery, and A2Z.

It’s not trash . . . yet

So what about all those boxes in the UW Libraries Special Collections and my storage unit?

In recent years, interest has been growing in and/or and in the history of the art, artist spaces, and political/social dynamics of its times, perhaps partly because of parallels that can be drawn with our times today. Interested curators, artists, historians, and others looking for photographs and other material from and/or have come up short. Although the materials at the UW are technically accessible, they’re hard to find and time-consuming to use. In addition, access to information about and/or is hampered by the fact that the organization came and went before the internet came of age, so there’s not much about it online. (A few news stories and other history websites are included in the “References” below.)

University of Washington. In fact, I’m grateful that the UW Libraries accepted and have protected and/or’s boxes all these years, but Norie and I were a little naive when we donated the material. The boxes included multiple copies of documents that we’d love to have now, and, most heartbreakingly, we gave not only prints but the negatives of Norie’s installation photographs. Copies, even of duplicates, come prominently rubber-stamped with University of Washington ownership terms, and prints from the negatives are expensive. (See references below for links to an inventory and Finding Aid for the and/or material at the UW Libraries.)

At the same time, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised that the materials have sometimes felt locked up and out of reach. After all, it’s the job of archivists to be concerned about preservation, not use. I’ve been advised that if I plan to actively keep using the files I still hold, I should hang on to them.

My storage unit. Until very recently, the and/or boxes I have in storage had been just as difficult to use, though for different reasons. While the boxes were labeled, they hadn’t been inventoried beyond simple box lists I’d created when I first put them in storage. Even with those lists, I couldn’t remember what was actually in them. and/or’s boxes were piled up with other boxes and ephemera from other years and other projects, in no particular order. My pack rat tendencies, perhaps exacerbated by an undergrad art history degree, compelled me to save much more paper than a reasonable person might. Besides stashing it away (and paying to store it), I haven’t paid much attention to it. In general, my focus has not been on my past. I’ve always been drawn to what’s in front of me and what might come next.

Maybe it was breaking through the 70-year-old age barrier that did it, but in the past several years I’ve begun trying to bring some order to the stored files. With help from a handful of UW art and library students, all of my approximately 150 stored boxes that may have historical relevance have been inventoried “to the folder level,” which means the inventory includes the headings on every folder in each box.

I’ve added a page to my website titled, ”It’s not trash . . . yet,” that gives background on how the inventories were created and what they include. The collection is divided into series, and I’m in the process of briefly describing each series and providing a download link to its inventory. (See references below.) The page is public but incomplete, and I’m currently seeking interns for the coming school year to work with both the files I have in storage and also with the and/or material at the UW.

![]()

Records and archives of and/or offshoots

The state of the records of and/or’s several offshoots vary considerably, from unknown and “they probably got tossed” to an expertly-organized archive with a classy website. Here are some of the main ones.

CoCA, Center on Contemporary Art was founded in part to fill the gap left when and/or closed its exhibition program in 1981, and it operated with and/or’s fiscal sponsorship until it got on its feet. During its nearly 40 years, CoCA has operated galleries and produced exhibitions, events, artist residencies, publications, and discussions. The CoCA Archives Project is evidence of what can be done with archives, both physically and digitally. The archive was created and directed by arts organizer and planner Anna R Hurwitz. Launched in 2013, the CoCA Archives collection includes printed materials, slides, video, and other materials. Anna, aided by archivists, historians, volunteers, and the support of 4Culture grants, has assessed the collection, begun preserving the material, written a Finding Aid, and digitized posters, videos, and slides. The physical archive is housed and managed by CoCA itself. Anna stepped into my life last fall after she enrolled in the two-year UW Master of Library and Information Science degree program. She has brought an invaluable, archivist’s eye to organizing my collection and remains my go-to person for counsel on my archives project.

Artech, the for-profit company that and/or launched in 1978, was recently purchased by an Australian fine arts handling firm, though Artech’s name and personnel remain the same. The one founding member still on staff, artist Mike Hascall, was commissioned by the new owner to write a history of the company. Not a Straight Line: The first 40 years of Artech Fine Arts Services is scheduled for publication in December 2018 for “in house” use, but with luck it will also be available online. Over the years, Mike has also been “squirreling boxes away,” not letting the records be destroyed. Because he used and organized the records as he wrote the history, Artech’s archive will be in good order when he leaves. Annual reports, which were produced for most years, form the backbone of the history. The archive is still held by the company and hasn’t been donated to an institution.

Artist Trust began as and/or’s program of small grants that spun-off when and/or closed. After much planning and development, it launched independently in 1986. Now, it is a robust state-wide nonprofit in Washington state that supports artists in all disciplines and in many ways. Like Artech, it still holds the organization’s records. Of its archives, Artist Trust’s current director, Shannon Halberstadt, says:

Artist Trust has a treasure of archives, including documents, contracts, publications, and marketing collateral from over thirty years of supporting artists. It’s amazing to dig in the archives and find articles from decades-old Artist Trust publications to share with artists, grant panelists, funders, and stakeholders, underscoring the impact of our work over time. There’s the newsletter with a photo of a young Kyle MacLachlan in his native town of Yakima, or the one with an announcement of Gary Hill receiving an Artist Trust Fellowship award. These archives not only give us a sense of organizational history, they also allow us to reflect and learn about different stages of our organizational growth – lessons we can use and share to further the field of artist support. Seriously good stuff in these archives.

911 Media Arts Center was created from the merger of Focal Point Media Center and the Nine One One resource center, two entities created at and/or’s dissolution. After about 25 years, 911 Media Arts Center closed quietly on August 8, 2014. Former board members, Carole Fuller and Kurt Kiefer, pulled together all the 911 files they could find, sorted through them, returned artists’ media when they could, and put the rest in the hands of a curator at UW Libraries Special Collections. They don’t know the current status of 911’s files within the UW’s collections.

![]()

Why go to all this trouble? What good are archives anyway?

The value of archives to art and cultural historians is undisputed. But the material also has great value as living history, as part of an active, contemporary culture. My recent experience with student interns demonstrates this.

In 2016 I helped create a year-long “Alum in Residence” position for myself at the UW School of Art + Art History + Design. While there I turned a handful of undergrad art and art history interns loose on the records of one of the bigger projects from my past, Arts Wire, an early national online network for the arts, started in 1989. The students began by working on an inventory of what was in the 16 Arts Wire boxes, but quickly began actually reading the documents. This unleashed an interest in a historical time (late ‘80s and ‘90s) that seemed to them relevant today and also raised questions such as, how does something like Arts Wire get started? how did your generation deal with the culture wars? what was the world like before the internet? is making something like this art? when does history begin? The questions came along with a realization that “This is history . . . and you’re still alive!”

Over the course of the year, not only did the students continue plugging away at the inventory, they created two exhibitions, one in the school’s coffee shop and one in its gallery, as well as a 14-episode podcast. For the podcast they interviewed people who’d been involved in Arts Wire from places such as New York, Ann Arbor (MI), San Francisco, St. Paul (MN), Seattle, and from as far away as Bali. It was clear to me that the students wanted to share the history and ideas they discovered, to take what they found in the boxes and move it out into a continuing dialog with their contemporaries and others in physical and digital spaces.

The history they encountered in the archives gave them a tangible point of departure for conversation and shared understanding. Each of the interns wrote a piece at the end of the year. Short excerpts from essays by two students provide insights into the value of the archive experience to them.

This internship turned out to be much more than simple archiving…I have gotten a look into a history where, luckily, my subjects are still around. I have been able to talk to them about the files I have been going through. Because of our podcasts, I learned about the problems that were occurring at the time and what they felt about it. – Jessica Capó

At the heart of the experience was building a connection across generations that allowed me to stretch academically and personally… Within the files we found many tantalizing concepts and issues which were (and are) relevant to the present moment. Rather than simply become aware of such continuities, we wanted to work with them and explore the possibilities they offered; the intent was to pull the files into the present and to use them as a starting point for contemporary engagement and understanding. – Karen Beech

This archive, like that of and/or, remains open-ended and incomplete. There’s still work to do to make the material useful and “discoverable,” to use a library term. The archive can still be refined and added to. And through the direct engagement of people like Jess and Karen, 30 or 40 years later, the history in the boxes is coming back to life… the bones are dancing again. It is as if they were awake.

![]()

References

- My introduction’s epigraph comes from Alternative Art New York, 1965-1985, an anthology edited by Julie Ault and published in 2002 by the University of Minnesota Press.

- The “goodnight” poster was designed by Wilkins & Peterson with illustration by Gary Jacobsen and copywriting by John Koval.

- “Standing on slivers of history,” Amanda Manitach, City Arts, June 24, 2014.

- “and/or, enough structure and enough openness,” Anne Focke, Temporary Art Review, November 5, 2015.

- “and/or (Seattle arts organization),” Jen Graves, HistoryLink.org, June 26, 2013.

- And/Or Gallery Records 1969-1985, Archives West (a Finding Aid).

- And/Or Gallery Records, Inventory.

- “It’s not trash . . . yet” Anne Focke, archive reference page on the website, Carrying On. All the boxes I hold in storage are organized into series. and/or files are found in the “073” series, in boxes numbered 031, 032, 033, 034, 035, 036, and 112. Related files are in these boxes: 103 (Artist Trust), 108 (culture wars, NCFE, etc), 109 (NAAO), and 114 (a few things from CoCA). This inventory can be downloaded by clicking on the 073 series link.

- CoCA Archives Project.

- CoCA Center on Contemporary Art.

- Artist Trust.

- Artech.

- “It can and will change: Why 911 Media Arts Center is worth saving,” Jen Graves, The Stranger, August 13, 2009, about the last days of 911.

About the Arts Wire archive project

- “Archaic Social Media – Arts Wire uncovered,” Anne Focke, Carrying On, February 11, 2017.

- “This is history and you’re still alive!” Anne Focke, Carrying On, July 29, 2017.

- AND_NOW? a podcast produced by Jessica Capó, Karen Beech, and Lizzie Trelawny-Vernon, February-June, 2017. Choose “Extras” on the menu for brief information about each podcast, including topic and interviewee. Choose “Podcast” on the menu for a simple list of links to each one. They’re each about an hour long.

This essay was possible because of a commission from Common Field and support from the Jini Dellaccio Project, a fiscally-sponsored project of Artist Trust.

![]()