On a chilly Sunday morning in March, my granddaughter Livia and I went on an adventure through a nearly-deserted downtown Kansas City. Judging from her response, there’s nothing quite like the joy of cartwheeling through an empty passageway between a mall and a hotel lobby. She showed me how to use the slow-motion video function on my phone and then continued wheeling back and forth in front of the fountain. She found it hard to stop.

For as long as I can remember my natural instinct has been to be hopeful and positive. I see possibilities and go for them. My parents encouraged me or, at least, stayed out of the way enough that the impulse stayed alive. I still carry the residue of a childhood belief in Annie Oakley’s, “I can do anything.” The sense of possibility I get from leaping into things to see what I can do feels akin to Livia’s cartwheeling spirit.

That spirit has certainly been tested over the years, seldom more than it is today by the state of our political and economic world. Can we really do anything? I’m convinced we can, and I’m egged on by a positive frame of mind that I just can’t shake.

Several decades ago a friend, Jennifer, sent me a postcard because it reminded her of me. Despite pack-rat tendencies to save documents and memories on paper, I can’t find the card now, but I remember it being a black and white photograph of a cobblestone street, in what I took to be early 20th century Paris. In the middle of the street, a man had popped his head out of a sewer, the round sewer cover on his head and a big smile on his face. My memory is that he looked happy, even a little giddy as though asking, what’ll we do next?

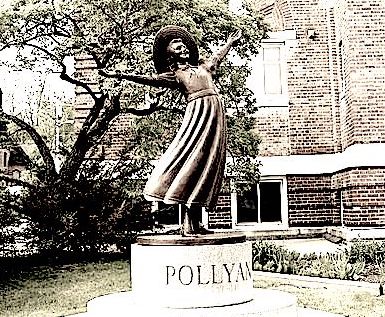

Jennifer wasn’t the only one who pegged me as cheerful. I remember being asked once, why I seemed so happy all the time. Since I couldn’t think of a good reason, I said something like, “It’s just easier this way.” More than once in the past, I’ve been called a “Pollyanna.” This may partly have been because nicknames tend to play off one’s own name, but I’m sure it also had something to do with my general disposition. At first being called Pollyanna seemed complimentary or just descriptive. More and more, though, I began to cringe when I heard it, feeling its pejorative undertones. I was embarrassed. Was my cheerfulness irrational or annoying? And who was Pollyanna anyway?

Pollyanna, a 1913 children’s novel by Eleanor H. Porter, told of a girl who got through a terrible childhood by playing what she called her “Glad Game,” in which she found something to be glad about in every situation, no matter how dreadful it was. Briefly summarized, this might not sound so bad, but colloquially, “Pollyanna” has come to mean being foolishly or blindly optimistic, sometimes responding insensitively to terrible things. The adjective Pollyannaish has a male parallel in “Panglossian.” Dr. Pangloss, in Voltaire’s Candide, was “an incurable, albeit misguided, optimist who claimed that ‘all is for the best in this best of all possible worlds.’ So persistent was he in his optimism that he kept it even after witnessing and experiencing great cruelty and suffering.” (Merriam-Webster)

Even when I was younger, I knew this wasn’t the way my energy worked. I’ve never felt that taking a positive attitude into the world denies the conditions I find there. Being aware of suffering or unfairness can in fact move me to act, to see what I can do about it. I wouldn’t characterize my actions as playing a “glad game,” even though something like gladness can come from it. There’s a kind of joy in figuring out what can be done to right a wrong, find a solution, or discover a new way to see an old problem. My hopefulness lives, at least partly, in often small but ultimately positive acts.

I long to talk more about why or how I can be positive or hopeful now, but it’s not easy. I stumble when I try to write about it. I struggle with the words when I try to talk about it out loud. Hope and possibility can feel sort of wimpy and irrelevant. There always seems to be something more important and urgently serious. How does one take a hopeful stance in the midst of the fight for immigrants’ humanity or for protection of children and all of us from a lethal gun culture? What positive frame can one possibly create when democratic systems are failing and under attack and when we so urgently need to fight against more environmental destruction and against racism, the abuse of privilege, and increasing economic inequality?

If it’s not Pollyannaism or blind optimism that drives my hopefulness, what is it? And how in the world do I put that into words?

Whenever I get stuck and can’t seem to move ahead, I read, I listen, I learn and borrow from others to put the pieces together for myself. I can’t do it alone. Though I sit here now, by myself – trying to learn a little more and be clearer about my words – I’m not really alone. I’m surrounded by what I’ve pulled together from reading, from my own immediate experience, and from what I hear in other people’s stories.

As part of an early 2017 episode of WNYC’s On the Media, Robert Garfield interviewed writer, historian, and activist Rebecca Solnit.* He began by mentioning that her 2004 book, Hope in the Dark: Untold histories, wild possibilities,was again “flying off the shelves.” The interview began with her reading a passage from the book outlining recent historical instances of unexpected, often nonlinear ways positive change has happened. Despite these lessons from history, Garfield was troubled. “In the foreseeable future, he said, “we are likely as a society to go abruptly and maybe irretrievably backwards on civil rights, human rights, climate, sanity. Isn’t a man permitted to be morose and desperate without surrendering? Isn’t that a reasonable reaction to horrible events?”

Solnit replied:

You’re talking about two different things: How do we feel, and what do we do? I’m not telling people how to feel. I’m telling people that there is scope for action. One of the great conundrums is that unless we believe there are possibilities we don’t act, but the possibilities only exist if we seize them.

I’m not an optimist. Optimism believes everything will be fine no matter what we do, and therefore we don’t have to do a damn thing. Pessimism is the mirror image of that that believes everything is going to hell in a hand basket, and it gets us off the hook. We don’t have to do anything. Hope for me is deeply tied to the fact that we don’t know what will happen. This gives us grounds to act while being clear that terrible things are happening.… There’s wiggle room in there. A lot of extraordinary stuff is happening and it’s happening in complex ways… We’re not talking about a future that’s already written.

Solnit inspires my determination to hang on to a positive orientation while not losing track of the conditions that keep me moving. One definition of positive is “concentrating on what is constructive and good.” That feels right to me.

My hope is not abstract. Hope can be an opening that gives us grounds to act, but it can also be triggered by stories of real people finding new, or sometimes bringing back old, ways of living and working together. It grows not just from the possibilities of an unknown future, but also from the actions, work, and ideas of real people who loudly, or often quietly, make a difference and show us new ways to live. Solnit reinforces my own observation that “a lot of extraordinary stuff is happening.”

Over the past year or so I’ve struggled to figure out the best ways I can respond to the current state of the world – to find my piece of the puzzle. One thing I’ve come to is that I want to contribute to imagining how we get out of this mess. Another way to put it is that I want to help answer questions like, Where is it we want to go? What do we want to be creating as we go forward, and how do we get there? For me, real-life stories along with leaps of imagination that tie them together are like fuel for my hopefulness.

Now and then in coming months, I plan to share stories I’ve collected and new ones I will discover, the kind of extraordinary stories that Solnit refers to. I also plan to write about some of the connecting threads, broad ideas or theories that draw on the various stories and that may tie them together and add to their potential and their power. As I write, I’ll try to avoid being blindly Pollyannaish without losing my own stubbornly positive voice.

Photo credit

The original photo of Littleton’s Pollyanna statue is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license. The photo is by David Fulmer, Daveynin, shown here with my modifications.

Note

* “Rebecca Solnit on hope, lies, and making change,” interview by Bob Garfield for WNYC’s On the Media, first broadcast on January 12, 2017, rebroadcast on December 28, 2017.

![]()