When I started living alone about 15 years ago, all of a sudden my daytimes on Thanksgiving Day were wide open. Since then, almost all my celebratory Thanksgiving meals have been with friends Norie and Ralph, who enjoy preparing the evening’s magnificent food with little help from us, the guests. So, what on earth, I wondered, does one do during the day on Thanksgiving without any hosting or cooking responsibilities?

Take a long walk, of course!

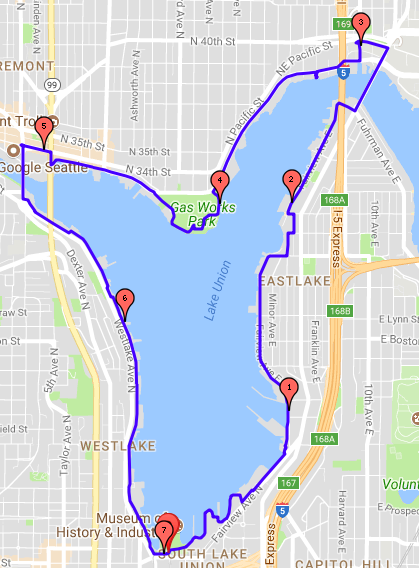

At the time, I lived downtown, an easy walk – about a mile – from the south end of Lake Union. So I decided to walk around the lake. I wanted to see how close to the water I could stay as I circumambulated. Over the course of about 6.5 miles, the terrain and the landscape change many times – from docks with fancy water craft and restaurants, to light marine industry, houseboats, small street-end parks, two bridges, a major regional park constructed on the site of an old gasworks plant, a couple of sea plane terminals, and much more. And the weather is just as changeable – rain, fog, clearing, sun, wind, drizzle – anything goes.

I always made curious little discoveries and encountered memorable characters. One year I passed the same couple twice, and we realized we were doing the same thing, just in opposite directions. We said, “See you next year!” though we never did. Another year I ran into a wild-looking guy on a little road that ran alongside a run-down ramshackle complex of buildings where I suspected he lived. As he chased pigeons away from the building, he muttered to me, “Too much society!” I smiled and scooted away hoping I wasn’t also too much society. When I got twenty yards or so down the street, he shouted, “Hey!” in my direction. When I turned, he gave me a big thumbs up, saying simply, “Thanksgiving!” You just never know where you’ll find joy.

One year, Norie took time out to join me. From her I learned that Seattle City Parks and Recreation had given “my” path an official name: “The Cheshiahud Lake Union Loop.” The City’s path doesn’t always stay as close to the water as my path did, though I suppose parts of mine were probably a little too sketchy to ever be “official.” But the course is marked with signs, and information about it is posted online.

The Loop is named for Cheshiahud, a Duwamish man, also known as Lake Union John or “Chodups,” who lived most of the last years of his life on the edge of Portage Bay, an extension of the lake. The photo below shows him with his wife Tleebuleetsa, also known as Madeline. Born in about 1820, Cheshiahud died in 1910. It was said he was the last of the Duwamish people to live a traditional, independent lifestyle near the lake, land historically inhabited by the Duwamish people and their ancestors. More about his life is here.

Eight years ago I began to invite friends to come along. We start our walk at 11 a.m. at South Lake Union Park. We head out, whatever the weather, walking counterclockwise. With a few side trips – to the lake at street ends, a photo-op stop at the north end, and a coffee break at the Fremont Bridge about two thirds of the way around – we allow about three hours, though it often doesn’t take that long. The weather is always a surprise – bright or gray, sunny, drippy, or down right wet. For the first shared walk, we even had snow on the ground.

Each year, we have a few stalwarts who walk almost every time, many repeaters, and always new people – young and old, very small children in strollers, and a nice assortment of dogs. One year, we picked up a few curious strangers part way around. The past few years, we’ve passed, or more correctly, been passed by, quite a caravan of families on bicycles of all sizes.

I’ve loved the way that, over the duration of the walk, people drift forward and back along our loose line of walkers, talking with both long-time and newly-discovered friends. All in all, there’s never been a year when I didn’t end the walk feeling invigorated and grateful, for the walk, for the weather, and most of all for the friends.

![]()

Note: The photo of Cheshihud and Tleebuleetsa was taken by Orion Denny, the first white male born in Seattle.

![]()