Finding a creative form in the yeasty chaos of people working together to make something new

Suppose you’re part of a group trying to find the right form to structure your work together. You share a vision. You’ve had some success. You have interested followers. Now it seems you need some kind of legal structure so you can operate in the world as it is. But legal forms come with limitations.

How far can you stretch a legal form? Or put another way, can you operate within a legal organizational form in nontraditional ways? Or perhaps even better yet for the purposes here, can you imagine a parallel but equally defining creative form that expresses the spirit and soul of the body of people working together?

To be more specific, suppose the group of people wanted a structure that embodied and fostered values of rigor, experimentation, responsiveness, difference in all its forms, difficult ideas, ground-level work, open communication, listening, collective action, transparency in governance and decision-making, and new forms of equity and power. What then?

This list of values includes words and phrases pulled from a longer statement of the core values of Common Field, an organizing network that connects experimental, artist-run, and artist-centered spaces, organizers, and initiatives nationally.1 And the questions are ones the network struggled with.

“Common Field” is the name eventually given to an organizing effort with roots stretching back before the name, at least as far as the early 2000s. The organizing began in the interactions among participants in a cohort of small, artist-driven organizations from across the U.S. funded in part and periodically convened by the Warhol Foundation. Sparked by these gatherings and through the vision, struggle, imagination, negotiation, tension, commitment, and lots of plain old hard work by cohort members, a network began to coalesce. Its form became visible through a national conference in Chicago (2011), a retreat in Saugatuck, Michigan (2013), a national convening in New Orleans (2013), and another in Minneapolis (2015) where Common Field as a member network was first announced. I wasn’t part of the founding cohort, but in 2015 I was invited to participate in the organizing.

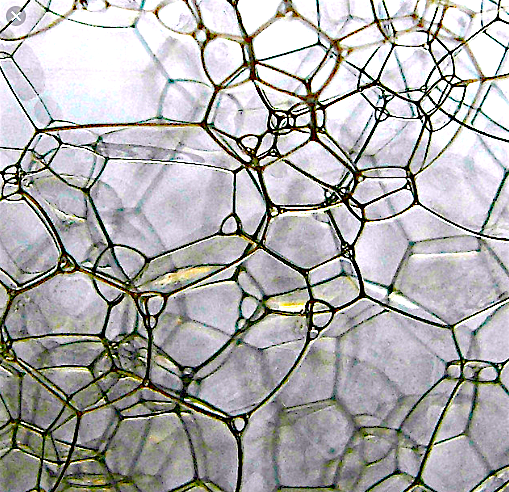

Throughout these first years the network had an energetic but fairly amorphous form. Legally, it operated under the fiscal sponsorship of one of its member organizations. Having often participated in what can feel like the murky chaos of people working together to make something new, I was comfortable functioning outside a formal structure. I liken times like these to the dynamism of an estuary where, with fresh and salty nutrients, new life emerges.

![]()

Toward the end of 2016, it became clear it was time for Common Field to become independent, especially in light of the growth of its membership, its annual convening, programs, and budget. I was a member of the governance team charged with overseeing this process.

Now you might think that creating a legal structure is rather boring, certainly not dicey or contentious. But Common Field was guided by deeply principled founding members who wanted an organizational structure grounded in the values they believe in, values that the current board continues to share. Not being a founder, I didn’t participate in early discussions, but as I understand it there was a justifiable fear that in adopting an institutional form Common Field could also be adopting the power dynamics, inequities, and closed hierarchical structure that we see too often in the organizational world around us, whether for-profit, nonprofit, or governmental. The governance team took this charge head on.

A summer 2017 newsletter put one of our conclusions this way: “We are in agreement that, while becoming a 501(c)3 nonprofit organization is imperative, it is just as imperative to model a healthy and evolving example of this organizational form to our network.” Martha Wilson – artist, founder/director of Franklin Furnace, and a fellow governance team member – gave us wise counsel that we kept repeating in our discussions:

We can’t change the structure of a nonprofit, but we can change how we operate within this legal framework.

At some point, in the midst of a governance team debate about fine points in our proposed bylaws, I took a mental side trip. Legal forms, it struck me, are only one kind of structure that a group of people might create to inform their work together. A second and complementary form could take advantage of the imagination we bring to it as artists. In fact, the words of artists helped me come to this conclusion.

![]()

In his 1983 essay, “People, Land, and Community,” Wendell Berry describes the faulty assumption that we can ever become smart enough to control the “demons at large.”2 He wrote:

The evidence is overwhelming that knowledge does not solve the “human problem.”

For our purposes here, I’ll replace “knowledge” with facts or rules or legalities. A little later in the same essay, Berry says, “It is simply true that we do not and cannot know enough to make any important decision.” He applies this to marriage, farming, and community. I suspect that, for Common Field, it’s also true that, to clumsily paraphrase him, “No legal form can ever solve our human problem.” What I take from this is that, as hard as it is to make a decision about Common Field’s legal framework now, the real work of making it a good decision will come later, in continuing to understand and adapt it and to make the decision actually work in the real world.

Then, in another essay, “Poetry and Marriage,” which is more explicitly about form, Berry wrote:

Properly used, a verse form, like a marriage, creates impasses, which the will and present understanding can solve only arbitrarily and superficially. These halts and difficulties are, perhaps, the true occasions of the poem: occasions for surpassing what we know or have reason to expect… One puts down the first line of the pattern in trust that life and language are abundant enough to complete it.

Maybe that’s what we’re doing now, writing the first line of Common Field’s pattern. And we have to trust that life and our actions together are abundant enough to fill out the pattern that we’ve begun. This same essay includes these memorable sentences: “It may be, then, that form serves us best when it works as an obstruction to baffle us and deflect our intended course…The impeded stream is the one that sings.”

![]()

A living form, such as an organizational structure, will constantly need tending, will constantly find new obstacles in its way. An insight from Martha Graham picks up this thought in an exchange recorded by Agnes de Mille in her memoir, Dance to the Piper:

The greatest thing [Martha] ever said to me was in 1943 after the opening of Oklahoma!, when I suddenly had unexpected flamboyant success for a work I thought was only fairly good, after years of neglect for work I thought was fine. I was bewildered and worried that my entire scale of values was untrustworthy….

I said, “When I see my work I take for granted what other people value in it. I see only its ineptitude, inorganic flaws, and crudities. I am not pleased or satisfied.”

“No artist is pleased.”

“But then is there no satisfaction?”

“No satisfaction whatever at any time,” she cried out passionately. “There is only a queer divine dissatisfaction, a blessed unrest that keeps us marching and more alive than the others.”

![]()

All this is meant to offer an expanded context for the governance team’s struggle to write bylaws, while maybe removing some of the pressure to get them exactly right, right now. And it sets up a question: In addition to putting in place the legal framework that Common Field needs simply to work in the world today, can we approach Common Field as a creative form? Can we create a larger form — that is, beyond or parallel to the legal structure — a form begun and periodically renewed by a restless desire for something always alive and always better, a container for imagination and aspirations held together by commitment and trust that can take us past the obstructions that baffle us now and through the many obstacles that will undoubtedly baffle us in the future?

The kind of form I’m imagining needs more than legal bonds to hold it together, to release all the possibility inherent in this field. To my mind, the legalities are secondary to the real form we need. Perhaps we can create an image or an action or a text that Common Field could re-stage or renew at its annual convening every year, a kind of ritual maybe. Perhaps it could begin at the convening this year, maybe something simple that could be continually adapted over time.

An example, though I’m not suggesting it for Common Field, comes from a late 1980s conference about “creative support for creative artists” that closed with a piece by composer/performer Pauline Oliveros. In a bright dining room at lunch time (that is, no soft lights, no candles), Pauline directed us to hum together in an easy-to-follow pattern. That simple act, in unison, seemed to set us up to leave the conference with a larger sense of ourselves as a whole. The experience stays with me still.

The culture we live in today, even more than in Graham and de Mille’s or even Berry’s time, is caught up in, or to my mind trapped by, “metrics,” measurements, and the rational. It’s easy to forget that that’s only one aspect of being human, only one side of what defines our relationships with each other. It would be an invaluable gift if over time its members constantly refashioned a creative form that expresses Common Field’s non-rational, unmeasurable spirit and soul. This would go a long way to helping it become the singing stream in Berry’s essay.

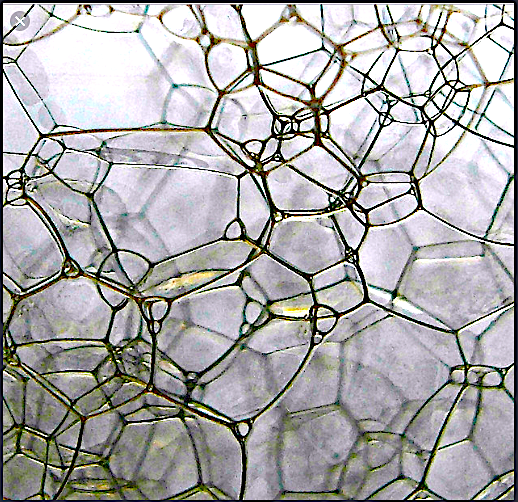

About the image

I was happy to find this image . . . it’s layered, both simple and complex, conveying a clear sense of structure that’s natural and pliable, but guided by clear underlying principles called Voronoi tessellations in mathematics. I know very little more about them, but this image of bubbles demonstrates Voronoi principles in nature — bubbles, that look as though they’re in the process of shifting slowly, maybe downstream.

Notes

- Common Field’s website address is: commonfield.org. The full statement of its core values can be found here.

- Standing by Words: Essays by Wendell Berry, published by North Point Press, 1983.

![]()