Arts Wire: A Secret Symphony?

Arts Wire: A Secret Symphony?

Lizzie Trelawny-Vernon

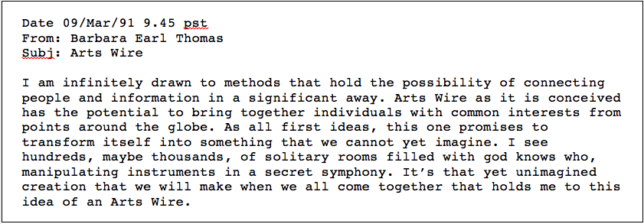

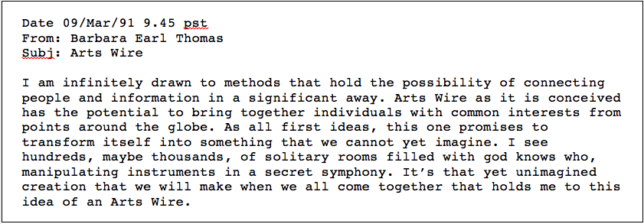

“A Secret Symphony.” It certainly has a ring to it. Yet, let us step back from the poetry of the statement and ask ourselves a few questions. What did Barbara Earl Thomas, artist/writer/thinker, mean by this, and was Arts Wire really like this at all?

Her vision of the internet and its possibilities is romantic. Her metaphor of music and poetry appears appropriate for an organization such as Arts Wire. The notion of many people chiming together as a united force fits well. Yet, the symphony is secret, perhaps because it is behind closed doors. Barbara implies you might not even know that someone was playing on the instruments next door – after all, the computer was silent.

Nevertheless, her vision for Arts Wire is somewhat contradictory. It proposes a world that is very connected, with “people coming together.” Yet at the same time, they are in “solitary rooms filled with god knows who.” What kind of world is this? Is a secret symphony some sort of anti-social social network?

There was certainly a kind of symphony within Arts Wire. Being “online” meant conversations could happen instantaneously across international and national borders, whatever the distance. Suddenly the world could spin faster; it could actually get on with things quicker. Response time dropped, and people could chime in time, creating a symphony of text voices. In the files we go through as interns, we commonly come across an outburst from an excited user that they “just got online!” – a crash of cymbals, perhaps, in our orchestra theme. Moreover, the connections that Arts Wire managed to create continually added people to the orchestra. For once, everyone was in the same hall, albeit a virtual hall, and could post, edit, and comment to make themselves heard within the orchestra.

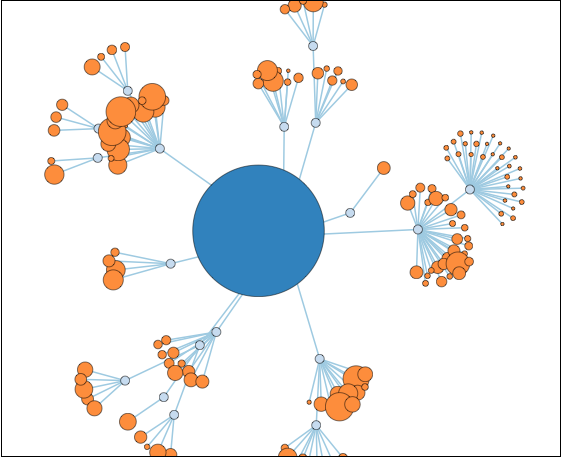

There was a conductor at the front, Anne, with her first violins, the Technical Working Group, along with the core staff and a mass of artists, organizations, and other folks taking up the other instruments. As with any orchestra, the instruments varied a lot. In Judy Malloy’s chapter on Arts Wire in Social Media Archaeology and Poetics, she tells how Arts Wire held the “vitality, diversity, and cultural significance” of its individual artists and nonprofit organization members at the core of its collective vision1 (p. 333). There were artists, writers, musicians, dancers, and theater artists chiming in together. Alongside these were the drum beats of critics, arts administrators, and arts funders, such as the NEA.

Arts Wire aimed to “reinforce democratic values and encourage interaction among its users”

Arts Wire, according to its mission statement, would “reinforce democratic values and encourage interaction among its users” in order, Arts Wire hoped, to “develop for artists a more integral place in society as a whole” (p. 335). At its height, Arts Wire hosted more than 100 websites for artists and arts organizations with links to more than 400 more (p.334). The mission of this collective body was to stand against the tides of the era’s culture wars that were pulling arts communities apart through censorship and restricted funding. The need for arts advocacy, as the founder Anne Focke explains, was great at the time. From our podcast interviews with various members of Arts Wire’s team and through examining the files, it seems that the relationships established through Arts Wire were not always harmonious.

Each person had their own personal interests. One big collision we came across was between artists and funders. We found posts that worried about what material was appropriate for Arts Wire with a concern that funders might see what they were doing and restrict their funding. Put into the context of the culture wars at the time, censorship was a fraught issue. In a discussion of privacy during a recent podcast interview, we interns had to question whether it is even right for us to examine all the Arts Wire material when it was never intended for our audience at the time it was created. So, if we’re part of a symphony, who are we performing for?

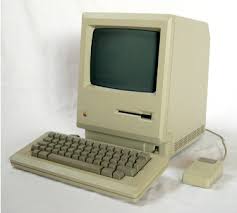

Furthermore, being online was a complex process that affected people’s ability to read and participate in the collective effort. Today it is simple to log on and have access, but in Arts Wire days, one first needed equipment: a computer, a connection (such as Sprintnet), then a modem, which was not always standard with computers then. You needed to pay to be online. You had to able to navigate the system using text-based commands, such as AND_NOW? And you had to have enormous patience for “the *very* slow connection” that Judy Malloy recalls. It was enormously confusing, the equivalent of a cellist picking up a tuba.

When I asked Anne what she found most challenging about it, she told me that, “It was really just getting my head around where I was, what was I actually doing, what’s happening, how was it all working, where is my message going? At the time there was no concept of the virtual world, and that’s really hard to explain to people today when internet use is so second-nature.” Not to mention, there was the difficulty of typing and navigating on a black-and-yellow or black-and-white screen. Clearly, you needed specific skills and imagination to operate in this virtual world.

Being online was a complex process that affected people’s ability to read and participate in the collective effort.

Immediately one must then think, who had these skills, and how did that affect their presence on Arts Wire? In the files, Arts Wire users complained of “not being able to type fast enough,” or feeling they needed to “read through everything before they even knew where they were or could even contribute to the conversation.” On top of that, people were concerned about their “persona” online: How formal should they be? Who was listening in? Was it even safe? It was at this time that “spam” came into being. (Spam was also present on fax machines, another new technology at the time. On one of our podcasts, former Arts Wire staff member Barry Lasky reported that spam could literally print itself out of your fax machine.)

For all the good the internet does, it’s important to recall that its history, and Arts Wire’s history along with it, is represented by those willing to take the risk and able to invest the time and money to master the tools and the material. Who could play these instruments and meet together in these rooms? And was everyone following the conductor?

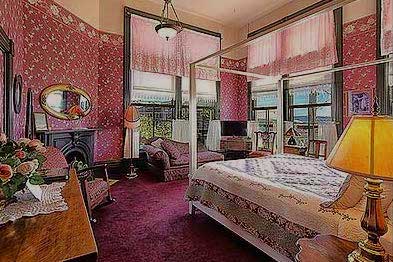

Arts Wire was not-for-profit, but one had to pay to be online. For Barbara Earl Thomas to have sent the message above, she first needed a computer. In 1991, a midrange computer with 4MB of RAM, a 200MB hard disk, and 14″ display would cost about $4,300. Cheaper computers were available but none less than $2,000. A considerable expense, would it be worth the money and effort just for a volunteer effort? Then, it cost money to be online. In 1991, a subscription to HandsNet (another early public interest online network) cost $270 annually, not including other connection costs. The costs of using Arts Wire included “choose-your-own” subscription fees of $5-15 dollars a month for an individual or $2,500 annually for partner organizations, plus a monthly fee from MetaNet, whose platform Arts Wire used, and whatever your own local internet service charged, which was usually a charge by the minute. Did the users have to pay these fees? Well, for the majority of users, the answer was yes. This all meant an individual would need to be fairly well off to afford to be online, and it would be more expensive if you were not a fast reader or typist. In fact, we know from Anne’s boxes, that her tactic was to print out posts from online, sign off, draft a reply, and then cut-and-paste it as quickly as possible when back online.

It’s important to recall that the internet’s history is represented by those willing to take the risk and able to invest the time and money.

The fact was that Arts Wire’s user and partnership fees were an important part of its budget, even though it also received foundation support and both in-kind and financial support from its home base, the New York Foundation for the Arts. All of which meant, though, that our Arts Wire community was narrowed to something that, in another context, was dubbed an “elite-internet-culture.” The mission of Arts Wire may have been for artists to have “a more integral place in society as a whole,” but to be an “integral person” on Arts Wire you needed the necessary money and knowledge. Arts Wire’s conversation, its “orchestra,” seems not only to be made up of a special few with access to funds and online knowledge, but each participant could only chime sporadically, not together. They were not in sync, they didn’t keep time. The notion of the instantaneous ‘”chat,” like the emoji we discovered in the files, was truly in its infancy.

Another problem this orchestra faced, as it headed boldly into the computer world, was focus and cohesion. With much enthusiasm, many groups created their own spaces for conversations about their specific interests and to find audiences. Over 80 interest groups were created, according to Judy Malloy. (p. 339). As she notes, this weakened the central place of Arts Wire. The burning fire at the heart of the house was no longer so easy to find. Conversation threads also died out, and their occupants moved away to websites of their own. It was therefore hard to keep up with Arts Wire itself.

This sense of losing track is related to an issue that we interns and Anne spoke about, together and in our podcasts. Today, we face threads from twitter, facebook, tumblr and reddit. It is easy to loose track, to not feel integrated. At the same time, we do not want to feel told that we must live in the virtual world – the anti-social social network.

We do not want to feel we must live in the virtual world

– the anti-social social network.

Sometimes this sense of losing control is not felt just in conversations online but also in the technology itself. Just as today an iPhone 6 is replaced the next year with the iPhone 7, in Arts Wire’s day the technology was also rapidly adapting, and by 1994 the World Wide Web changed Arts Wire’s audience, interface, and outlook. The development of technology, one could argue, even controlled the character, motivation, and drive of Arts Wire. By extension, helping its users continue adapting to the changes would be its greatest challenge. Making sure that if the violin went out of tune, the problem could be fixed without the utter breakdown of the song.

So why did they do it? Why did they bother to exhaust their emotional and intellectual energy learning to use these computers? And what were they getting from it?

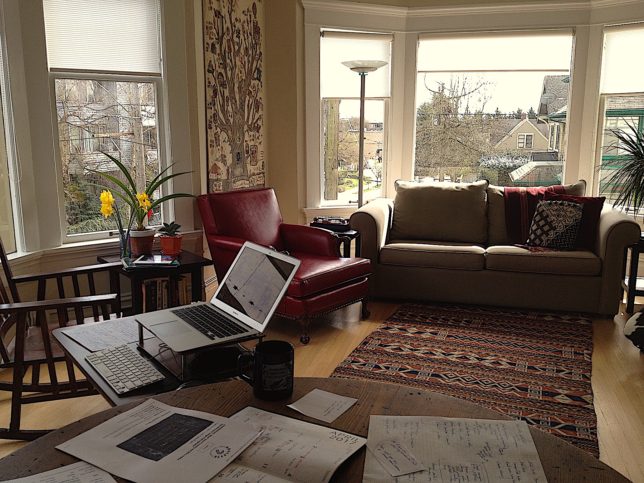

Let us set the context. The culture wars under the Reagan administration threatened the funding for the NEA, and the national government did not recognize the full value of artists. The role of the artist in society seemed to be changing, becoming more activist. While Barbara wrote of “solitary rooms,” I think what the artists involved in Arts Wire got was a sense of the wider community and kinship with each other. From our podcast interviews I have picked up on the fact there was a real “family” behind Arts Wire. The reviewer Kenny Greenberg in Internet World observed that, “It is the human spirit that makes Arts Wire special.” For Judy, it was this budding community that made Arts Wire “a lively place” (Judy Malloy, p. 337).

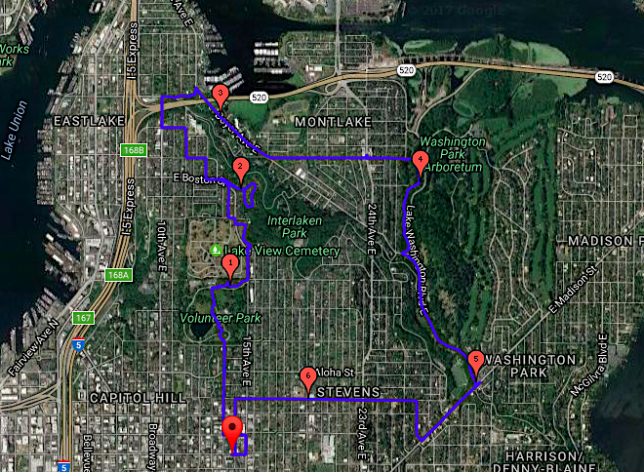

Furthermore, they had to use computers. The pioneers on Arts Wire knew that their world was changing. They were ambitious, and they took the gamble with the technology. They did the heavy lifting for us today and indeed continue to. Ted Berger, Joe Matuzak, Tommer Peterson, Judy Malloy, Anna Couey, Sarah Lutman, Barry Lasky, David Mendoza, and many others we weren’t able to interview have not lost contact with each other, and many are still invested in the art and computer world. By 1991, when Barbara was writing, Anne had already established a national steering committee and linked prospective artists and funders together from all over the country. After Anne left, during Joe Matuzak’s time as director, Arts Wire’s reach became international. Overseas communication was now a reality. These connections really were the crux.

So why did they do it? They were ambitious, and they took the gamble with the technology. They did the heavy lifting for us today.

In comparison to what had come before, this was astonishing. Here was an online group where people from all over the country and all walks of life were commenting in one place, at a time “when the national arts support was in crisis.” (Judy Malloy, p. 336) In theory, the kinship Anne orchestrated was remarkable. As the conductor, Anne recruited a wonderful team of musicians, even if they did sometimes have trouble with the instruments and keeping time.

What about in my own experience as an intern? I believe that this “symphony” metaphor has played out in our lifetimes. As Arts Wire wrote the manual, reached out to non-users, and helped artists on the way, they were “tuning” the instruments that my generation plays today without thinking about it. Despite its virtual presence, what I have been struck by is the memory of Arts Wire among people today. As an intern, it has been my role with my team to do the work of Arts Wire again, bringing its artists and organizers together, in a kind of reunion (albeit easier to do now) to ask them what happened and how they felt. In doing so, I have made my own connections, with Anne, Zach, Karen, Abby, Jessica, and everyone we interviewed.

In a funny way, we have come full circle, with a desire to create an artistic community all over again. We have joined Anne in conducting the symphony.

Today, kinship in the art world will be more important than ever.

The people we have interviewed have such a strong willingness and enthusiasm that they’ve taught me an important lesson. The art world and the UW art department in particular have a vibe of kinship. I do not believe there is anything “secret” about it. From the start, there was nothing “solitary” about the artists or Arts Wire as an organization. Today with the recent threat to the NEA under the Trump administration, kinship in the art world will be more important than ever. If the NEA were to end, it would not be the end of arts. Creativity is grass-roots and it will find a way. Continuing with the orchestra metaphor, I do believe that the show will go on…instruments in tune, or not.

Lizzie Trelawny-Vernon is an undergraduate Art History student who spent a year-abroad program with us this past year and is now traveling the western U.S. on her way home to the University of Edinburgh.

Notes

- Social Media Archeology and Poetics, edited by Judy Malloy, MIT Press 2016.

Arts Wire: Time in a Carpet Bag

Arts Wire: Time in a Carpet Bag

![]()