Our dependence on digital data and infrastructure expands both the options for civil action and the levers and forces by which it can be restricted.

–Lucy Bernholz

Preamble: A piece of the puzzle?

Back in February, I wrote of struggling to find my place in the political, economic, and social circumstances of our world today. What is my piece of the puzzle in building up a countervailing force? 1 I’m still sorting this out, and now I suspect there’s not one but several pieces.

One puzzle piece is informed by my work with Lucy Bernholz, director of Stanford’s Digital Civil Society Lab and self-defined “philanthropy wonk.” For the last nine years I’ve been lucky enough to work with her as editor and sounding board for an annual monograph. Now based at Stanford’s Center for Philanthropy and Civil Society and director of its Digital Civil Society Lab, Lucy has deep practical and theoretical knowledge of philanthropy, and many people in that world have long looked to her for insights into their work. Over the nine years I’ve worked with her, her focus has expanded to encompass the whole of civil society and all the ways that, in her words, “people and organizations voluntarily use private resources for public benefit.” In this context, resources mean time, money, and expertise. She has also broadened the work to acknowledge and directly confront the fact that our civil society is highly dependent on today’s digital infrastructure and digital data, a dependency that brings both promise and peril. This work and these interests led to founding the “Digital Civil Society Lab.” 2

The annual monograph that I get to work on is published at the end of each year and offers “insight,” “foresight,” and “glimpses of the future” that are meant to help readers anticipate and navigate the next year. In January this year I posted excerpts from the previous Blueprint. 3 This year’s edition will be published in mid-December — Philanthropy and Digital Civil Society: Blueprint 2018. At that point, you’ll be able to find it either at the Digital Civil Society Lab or on her blog, Philanthropy2173. 4 I’ll also post a link on this site. If you’re eager to read a Blueprint before then, you can check out all eight back issues here. 5

I love the process of working with writing by people I admire in part because it gives me a privileged view into their thinking. This is especially invigorating when the process allows for dialogue around ideas that matter to me. Working with Lucy has reinforced, challenged, and expanded my thinking. What work could be better than that?

Why might all this be a piece of the puzzle? Often a first step in changing something is better understanding what we’re dealing with. Learning from Lucy and doing what I can to help her insights be clear is part of it for me. Another is not hanging on to what I learn but sharing it with friends and posting it here. What follows is based on a couple of ideas from the Blueprint that’s underway right now, mixed up, I’m sure, with my own experience.

The dynamism of small and fluid

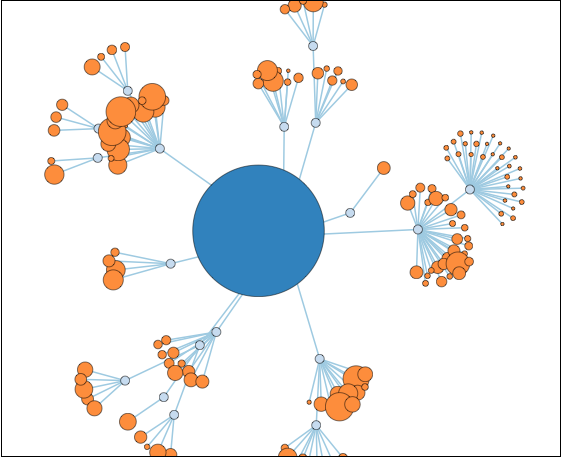

“We are surrounded by big, fragile institutions,” writes Lucy Bernholz referring to global companies, established political structures, and big nonprofits. This might seem to contradict what it feels like when we read the news and experience the impact of these large institutions on our daily lives. Lucy goes on, though, to point out that we can see their fragility in their mono-cultural, top-heavy, and increasingly rigid structures.

She contrasts these big institutions with the many small, fluid, and networked alternatives that exist all around us. In her words I recognize the kinds of informal groups, small organizations, and loose networks that have been home for the communities I inhabit and the work I do. The dynamism of the world of small groups isn’t changing, Lucy says, but she senses that their attitude toward big institutions is. The small have adopted a more challenging attitude toward the big and take a more confrontational stance than they did in the past.

From her vantage point at the Digital Civil Society Lab, Lucy specifically calls out small, networked “tech-driven alternatives to party politics, nonprofit or research-driven alternatives to corporate data monopolies, and crowdfunding of public services.” These groups, she reports, have often been purchased, suppressed, and ignored by the big institutions. And they “don’t see themselves as mere fleas on an elephant, rather they challenge themselves to be the termites that topple the house.”

A fluid array of these small, active alternatives function within civil society. In fact, along with many other groups and a set of behavioral norms, their participation constitutes civil society. As Lucy puts it…

Civil society is where those without power or critical mass can build both and influence the majority. It serves as a conduit to the majority system and a counterbalance to extreme positions. It also serves as an outlet for those actions, rights, and views that may never be the priority of a majority, but that are still valid, just, or beautiful.

Civil society is distinct from but overlaps with both the commercial marketplace and government, and it’s meant to be a place where we can come together to take action as private citizens for the public good.

![]()

Digital dependency

The Lab defines digital civil society as “all the ways people and organizations voluntarily use private resources for public benefit in a digital world.” It also refers to the space of digital civil society as “complicated,” and part of what complicates it is that most of digital space is owned or monitored by commercial firms and governments. For the most part, the designers of the tools we use and the rules that regulate our use of them are guided by corporate or governmental norms and not by the norms of civil society – not, that is, by a commitment to the common good or to individual rights (of free expression, peaceable assembly, and privacy), and not to pluralism or tolerance.

Much of the resurgence of political action and resistance among my various communities of friends functions in civil society’s small, fluid, and networked groups, fostered in living rooms, in coffee shops, and on the streets. And it also relies heavily on digital communication and on information gathered from digital sources. These tools facilitate many aspects of our lives and increase the ways we can organize, share information, and reach people across the city and the world. However, our dependency on the digital infrastructure also means we’re vulnerable to actions by both corporations and governments to narrow the space we have to operate in.

In the upcoming monograph, Lucy writes:

Our daily use of the most basic tools of the digital age such as cellular phones, email, or networked printers means that our activities are bounded by and reliant on the rules and tools of the companies that make the gadgets and wire the world. As we use these tools, our activities are also monitored by the governments that surveil the digital spaces in which our tools operate. Our actions in the space are shaped by the values of the companies that make the tools (even as the companies seek to deny it) and by the way we respond to being watched by both corporations and governments.

Lucy gives many examples of ways that governments and corporations can and have narrowed or closed the space for civil society, and her scope is global. Her information is based on direct observation and on engagement with people in countries around the world – that is, her examples don’t just reflect what’s happening here, in the United States. The restrictions she mentions may be familiar to many of us, but the list is long. A few include: Digital tools make it easier to monitor financial transactions and public assembly. Business models using digital systems can use social media to censor or confuse. Governments have a direct impact on nonprofit and civil society purposes by shifting funding and cutting off access to key data sets and sources. In some places, companies are allowed to charge different rates to different internet users. “Toxic company cultures, their seemingly unchecked power and influence over public policy, the manipulative power of their products, and their ability to be used as news sources are common news stories across the world, even in the polarized media of the U.S.” And this is only the beginning of identifying the ways that the space for civil society and digital civil society is closing.

Another challenge Lucy identifies is that “civil society advocates,” many of us, for instance, “are largely isolated from digital rights expertise.” Beyond this, much of the open source infrastructure that supports the tools used by civil society groups and individuals is sustained “by the voluntary, episodic labor of a remarkably few people.” The system is underfunded, she says, fragile and invisible. As I see it, most of the rules and tools of our digital dependency are invisible…so invisible, in fact, that much of it has come to seem intuitive and natural.

What to do?

My first impulse is to simply to share something of what I’m learning and encourage you to read Lucy’s next Blueprint when it comes out. Working on both this edition and previous ones has made me more alert to choices I make when I’m online and gives me new targets for my advocacy. So much of what we’re organizing and fighting for is a fair and open civil society, a space for the small, sometimes confrontational, ever-changing groups that work for the common good and individual rights. So I take these words of Lucy’s to heart:

Efforts to maintain an open civil society now require a much deeper understanding of how dependent we are on digital data and infrastructure and how much the digital world changes civil society’s relationships to state and corporate actors.

I’d like to be part of increasing that understanding. This issue of Blueprint reinforces my awareness that digital technology is, as Lucy puts it, “not inherently democratizing.” More of us have to become intentional about engaging with it. Gaining a better understanding of what we face also increases my awareness of just how hard it will be to change, especially since the impact of the way it works has become ubiquitous and invisible.

Another of the many things I love about working with Lucy is that, with all she knows and all the perils she identifies, she still ends Blueprint 2018 this way:

It’s audacious to think that civil society, globally, can reboot and reframe itself. I think it must. And it can.

Notes

1. What’s my piece of the puzzle? http://www.annefocke.net/?p=1793

2. The Digital Civil Society Lab, https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/digital-civil-society/

3. “We must fight to protect democracy in a digital age, Lucy Bernholz,” http://www.annefocke.net/?p=1681

4. Philanthropy 2173 http://philanthropy.blogspot.com

5. Eight years of Blueprints https://pacscenter.stanford.edu/blueprint/

The photograph of Lucy is from Perpetual, Limited, the Digital Civil Society Lab’s partner organization in Australia.

![]()

David Brooks, “After the women’s march,”5 also made a case that ”marches can never be effective opposition to Trump.” Their focus is wrong, he says, and grass roots movements only rarely lead to change, the civil rights movement being an exception; most change is made through the Democratic and Republican parties. He also says that the central challenge today “is to rebind a functioning polity and to modernize a binding American idea”—a coherent vision. That resonates with the discussion we’ve had of the need for reframing and for a new narrative, but his call for “a better nationalism” and one that balances “the dynamism of capitalism with biblical morality” doesn’t work for all of us.

David Brooks, “After the women’s march,”5 also made a case that ”marches can never be effective opposition to Trump.” Their focus is wrong, he says, and grass roots movements only rarely lead to change, the civil rights movement being an exception; most change is made through the Democratic and Republican parties. He also says that the central challenge today “is to rebind a functioning polity and to modernize a binding American idea”—a coherent vision. That resonates with the discussion we’ve had of the need for reframing and for a new narrative, but his call for “a better nationalism” and one that balances “the dynamism of capitalism with biblical morality” doesn’t work for all of us. Even finding new language isn’t enough by itself. New language also needs to help us get ahead of the moment and take a deeper look at how we understand and talk about what we hope to see happen. In a piece in The New York Times Magazine a few weeks ago, “Negative Energy”,6 the author, Beverly Gage, gives a brief overview of the history of resistance, and says that, today, we certainly have plenty to push against. But what are we aiming for with our resistance? She asks it this way, “If ‘yes’ seems impossible and ‘no’ seems insufficient, what fills the space in between?” And toward the end, she suggests that we need to think about “where we want history to go.” I thought, right. Where do we want it to go? This actually lies behind much of my concern. And going back to our discussion . . . the language, the new narrative, the reframing needs to reflect it, the “where.”

Even finding new language isn’t enough by itself. New language also needs to help us get ahead of the moment and take a deeper look at how we understand and talk about what we hope to see happen. In a piece in The New York Times Magazine a few weeks ago, “Negative Energy”,6 the author, Beverly Gage, gives a brief overview of the history of resistance, and says that, today, we certainly have plenty to push against. But what are we aiming for with our resistance? She asks it this way, “If ‘yes’ seems impossible and ‘no’ seems insufficient, what fills the space in between?” And toward the end, she suggests that we need to think about “where we want history to go.” I thought, right. Where do we want it to go? This actually lies behind much of my concern. And going back to our discussion . . . the language, the new narrative, the reframing needs to reflect it, the “where.” Then, in a recent Guardian Weekly, I found this: “Welcome to the Age of Anger,7” by Pankaj Mishra, with the subtitle: “The seismic events of 2016 have revealed a world in chaos—and one that old ideas of liberal rationalism can no longer explain.” One thing I like about his perspective is that it goes way beyond Trump and this election. It reaches 200 years back in time and outside the boundaries of this country to other parts of the world. Reading it helped me know that, If I’m to have any idea of how to move forward, I needed a better understanding of how we got here and what we’re actually facing. Mishra’s piece gives me a helpful, new place to start. Although, as the Guardian says, it’s a “long read,” it’s definitely worth it.

Then, in a recent Guardian Weekly, I found this: “Welcome to the Age of Anger,7” by Pankaj Mishra, with the subtitle: “The seismic events of 2016 have revealed a world in chaos—and one that old ideas of liberal rationalism can no longer explain.” One thing I like about his perspective is that it goes way beyond Trump and this election. It reaches 200 years back in time and outside the boundaries of this country to other parts of the world. Reading it helped me know that, If I’m to have any idea of how to move forward, I needed a better understanding of how we got here and what we’re actually facing. Mishra’s piece gives me a helpful, new place to start. Although, as the Guardian says, it’s a “long read,” it’s definitely worth it. Finally, to throw just one more (much shorter) piece your way, I was glad to find a fairly recent column, again in the Guardian Weekly, by George Monbiot, “The case for despair is made. Now let’s start to get out of the mess we’re in.”9 His piece starts to give me a more solid place to begin. He caught my attention when he referred to Mishra—for example, writing:

Finally, to throw just one more (much shorter) piece your way, I was glad to find a fairly recent column, again in the Guardian Weekly, by George Monbiot, “The case for despair is made. Now let’s start to get out of the mess we’re in.”9 His piece starts to give me a more solid place to begin. He caught my attention when he referred to Mishra—for example, writing:

Paradoxes abound. Some global indices show democracy on the rise around the globe, while other measures stress that spaces for civil society are closing. Since democracy depends on civil society, it’s hard to know how both can be true.1 In another head- scratcher, a year that was defined by the politics of lies also saw

an increase in the systemic faith in data and algorithmic analysis as guides to a better future. Resolution of these paradoxes comes down to human action—we must fight to protect civil society and democracy; they do not defend themselves. We must interrogate and make understandable the digital tools and data we use to make decisions, as they are simply encoded versions of our values.

Paradoxes abound. Some global indices show democracy on the rise around the globe, while other measures stress that spaces for civil society are closing. Since democracy depends on civil society, it’s hard to know how both can be true.1 In another head- scratcher, a year that was defined by the politics of lies also saw

an increase in the systemic faith in data and algorithmic analysis as guides to a better future. Resolution of these paradoxes comes down to human action—we must fight to protect civil society and democracy; they do not defend themselves. We must interrogate and make understandable the digital tools and data we use to make decisions, as they are simply encoded versions of our values. The New Colossus

The New Colossus