A “confabulation” provided one beginning point in a two-decade-long inquiry into what kind of space I want as a home and what relationship I’d like it to have with other people and the larger world.

![]()

Confabulate: to talk informally; chat. [Latin confabulari: com-together + fabula, story, conversation]; informal, confab.

In June 1997 a group of friends received an invitation to a confab, a chance to spend up to a week together in a beautiful natural location an hour and a half outside the city to consider “Home: Arrangements for living and aging.”

The invitation included this about the theme:

The confab was a chance not only to be part of discussions that could spin out from these ideas about home but also to simply try out our individual ideas by living them, together, in a cluster of small houses. Everyone invited was welcome to stay for all or some of the time to . . .

talk together (the “confab” part)

have time for yourself

share a few meals

sing or play or hike or . . .

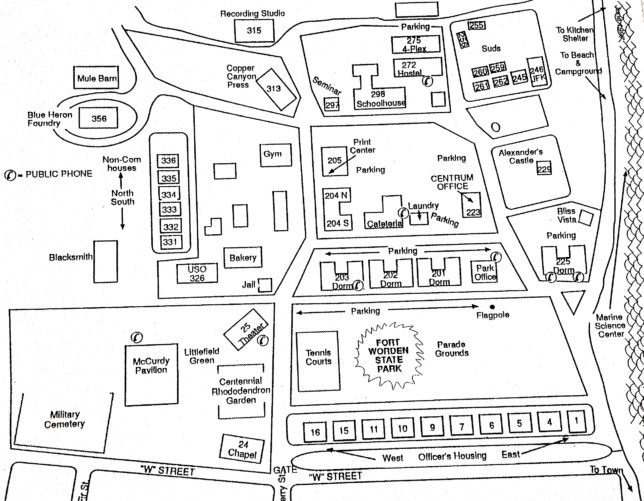

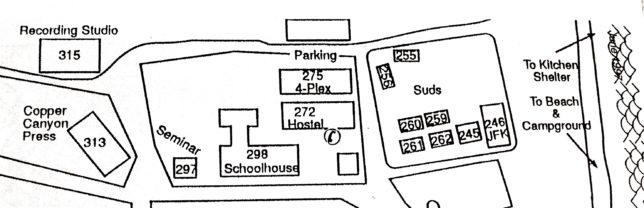

Five cabins at Fort Worden State Park served as our home base. Located on Washington state’s Olympic Peninsula on a high bluff overlooking Puget Sound, the park covers 434 acres with over two miles of saltwater shoreline. Originally designed as a military base in the early 1900s, it never saw active fire, and many of its historic buildings and battlements remain. In the early 1970s, it became a state park and a home for Centrum, a center for arts and education.

We occupied five of seven buildings that are collectively called, for reasons still mysterious to me, the “Suds” houses. Over the course of the week 21 people participated, including four children of participants. A few of us were able to stay the entire time, others were there for as many days as they could manage. I was given use of the houses as part of a deal I made with Centrum in exchange for services I’d provided in planning and reshaping their artist residency program in the Suds.

We occupied five of seven buildings that are collectively called, for reasons still mysterious to me, the “Suds” houses. Over the course of the week 21 people participated, including four children of participants. A few of us were able to stay the entire time, others were there for as many days as they could manage. I was given use of the houses as part of a deal I made with Centrum in exchange for services I’d provided in planning and reshaping their artist residency program in the Suds.

A focused time for conversation was scheduled each day, with many of us taking turns identifying talking points. Our discussion ranged widely: the relationship between the place where you grew up and the place you make for yourself later in life; balancing time alone and time with others; asking ourselves who we want to live with; distinctions between private and public space, or maybe better put, between private, public, and social or shared space. For some, work is an important part of “home,” as it is in artists’ live/work spaces. Would common spaces be too distracting for concentration? For some “a shared space should begin with a stove!” but others felt 50 years of experience would make sharing a kitchen really difficult. We need new language – “commune” doesn’t work; perhaps proximity rather than communal better describes the aim.

We considered city/country and urban/rural preferences and getting beyond the stereotypes; the importance of wildness; relationships between home and landscapes; the desire for a long view and for close-up views and a sense of enclosure.

Ideas about “a place to age and keep on living” from the invitation wove in and out as a theme (and we were 20 years younger then!): the anxiety about how we’d sustain our lives after “retirement;” our dissatisfaction with the isolation of today’s retirement communities; our role as the advance guard of the baby boom; the desire not to segregate ourselves according to our age; the value and importance of connections with the “larger world;” the importance of a place being “kid friendly” as well as questions about how a single person would fit in a multi-generational setting. We heard both of a desire not to be a burden to others as we age and also of the joy generated by caring for an older friend.

We described individual fantasies about what this might look like: a lodge; a hotel as a place that’s inviting not just to its residents but to outsiders; spas, resorts, and other escapes; sustainable eco-resorts; Buddhist retreats; taking over a whole city block that faces outward on the street fronts and inward into more private central spaces; W.S. Merwin’s description of a region in southern France.

Specific examples and stories added to our ability to imagine the possibilities: the Western Front in Vancouver, BC and its rural extension, Babyland; Chevy Chase on Discovery Bay; the Linger Longer Lodge in Quilcene; the Mountaineers’ lodges; Project Row Houses in Houston; and examples from co-housing projects and Seattle’s Anhalt apartments to clusters of homes built of a shipping containers.

Over the course of the week we also shared at least one meal together each day. Notes from the week refer to: “a wonderful dinner of David’s fish soup,” “a special meal of Laura’s cabbage rolls,” “Lynn and Rita’s salmon dinner,” “pasta from Jim,” “soup and sweet potatoes from Marcie,” “Norie’s pasta and Anne’s roasted vegetables,” and pizza from a Port Townsend cafe. In addition to solitary walks, time for reading, and pick-up games on the lawn, shared experiences punctuated our time: “a walk on the beach and sitting around a bonfire,” “Hillela’s banged up knee,” “Tomo playing nearby on the beach as it got dark,” “a sunny morning at low tide and a rainy afternoon visiting Port Townsend’s Secret Gardens.”

By the end of the week it felt as though we’d only just begun. We didn’t reach a conclusion about a specific future direction and didn’t resolve the many, often contrasting thoughts and stories. The week’s experience, however, did spawn more confabs that included more people and continued for four years until mid 2001. During this time, interest in the idea spread, and my mailing list for notes from the confabs grew and stretched across the country.

««««««•»»»»»»

That first confab marked the beginning of a conscious exploration of the meaning of “home” – the particular configuration of physical, social, emotional, and creative space that altogether means home for me and for others. Deep in my interior somewhere, home has always been both a private and a social place, shaped as I was by the first home I knew.

![]()

About a decade ago, not long after she turned 80 and I turned 60, Helen Gurvich and I made a lunch date, something we enjoyed doing whenever we could get our calendars lined up (hers was often as busy as mine). When she walked into the room that day she looked especially beautiful, just glowing with energy. My immediate reaction was, “Gee, you look great!”

About a decade ago, not long after she turned 80 and I turned 60, Helen Gurvich and I made a lunch date, something we enjoyed doing whenever we could get our calendars lined up (hers was often as busy as mine). When she walked into the room that day she looked especially beautiful, just glowing with energy. My immediate reaction was, “Gee, you look great!”