“Successful economic development must be an improvisational drift into unprecedented kinds of work that carry unprecedented problems, then drifting into improvised solutions, which carry further unprecedented work carrying unprecedented problems…”

Jane Jacobs

Cities and the Wealth of Nations

The 100th anniversary of Jane Jacobs’ birth is being celebrated this year by many people around the world. Jacobs is best known for her first book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities (1961), a powerful critique of 1950s urban planning. Her influence on the field of urban planning is considered revolutionary.

My own introduction to her thinking, though, was a different book, Cities and the Wealth of Nations, written more than two decades later (1985). In what seems to me a natural extension of her thinking about the physical form of cities, she had begun to consider the economy of cities, to “probe the mysteries of economic structure,” as she put it. In this book I found, as I wrote at the time, “new ways to connect artists and the world of economics.”

After reading Cities and the Wealth of Nations, I invited Jacobs to participate in a 1988 conference I was organizing about “creative support for artists” because I saw in her ideas a place for artists in economic development as she described it. She wrote back and, though declining my invitation, sent me a copy of her book, The Economy of Cities (1969) because of my interest. A source for this book was a question she asked herself: Why do some cities decline and die while others live and grow? A common assumption she challenged is that economies depend for their growth on large industrial and economic institutions – the huge modern corporations that are still so dominant. In Cities and the Wealth of Nations she took this inquiry further.

In a 2001 interview, when asked what she’d be remembered for most, she said, “the most important thing I’ve contributed is my discussion of what makes economic expansion happen. This is something that has puzzled people always. I think I’ve figured out what it is.”1 When she wrote Cities and the Wealth of Nations, she hadn’t quite “figured it out” yet (a summary of her economic theory came later in The Nature of Economies, 2000), but I found plenty in that book to expand my thinking.

Cities and the Wealth of Nations was in the pile of books I took with me to the Headlands Center of the Arts in 1991 where I spent 10 days reading, reflecting, and writing to pursue my inquiry into why artists didn’t seem to fit into the economic structure of our society. As I went along, I captured my thoughts in a paper, Artists and Economics: Notes from the Headlands. The section on Jane Jacobs follows here.

The act of writing the paper more closely resembled taking notes than writing a finished essay. It was a way of recording ideas that impressed me and that I thought might be useful at another time – as a source of more writing or as support for action and finding new directions. The paper remained open-ended, especially since I thought of it as notes for future use. It’s fun to pick it up again now and see how I’d argue with my 25-year-younger self.

Anne Focke, 2016

Jane Jacobs

I bought Jane Jacobs’ Cities and the Wealth of Nations by mistake. I thought I was getting her earlier book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Cities and downtowns were very much on my mind at the time (1985-86). Besides, economics is not a subject I’d have been drawn to intentionally. A dry and mostly unmemorable college course on economics left me with the impression that economics was fairly unrelated to daily life. About all I remember is something about sole proprietorships and the structure of corporations, plus larger and even more intangible concepts like “capitalism” and “socialism.”

When I bought Jacobs’ book, I was very concerned with how money moved around and how to get it flowing to things I cared about – to artists and work and activities I valued. In the 70s and 80s, I had been responsible for and had tried to raise money for a small, non-profit, artist-run organization named and/or. Fundraising for this organization was not an easy task. I began to realize that the problems I faced were not just my own; the artists and art work I cared about typically struggled financially. My interest in getting money to artists led to other efforts: working to establish an organization to support artists in Washington State (Artist Trust) and organizing a national conference on “Creative Support for Creative Artists” that delved into the topic of how artists are (and mostly are not) supported by our society or by the communities where they live. For the most part, though, something called “economics” was not on my mind.

“Probing the mysteries of economic structure”

Jane Jacobs writes of “probing the mysteries of economic structure” and the “rise and decline of wealth.” The first chapter of Cities and the Wealth of Nations, “Fool’s Paradise,” recaps much of the history of economists’ work and concludes that “several centuries of hard ingenious thought about supply and demand … have told us almost nothing about the rise and decline of wealth … We are on our own.”

The understandings that Jacobs reveals and weaves through her writing, both in this book and in an earlier one, The Economy of Cities (1969), appeal to me in part because they seem drawn from real circumstances, from close attention and observation, and from making connections among the things she discovers rather than from applying abstracted theories or handed-down principles. I didn’t need prior knowledge to follow along with her and to “get it.”

One of Jacobs’ principal points is that cities are the basic economic unit, not nations. Most economic thought proceeds with an assumption that nations are the primary economic unit. Jacobs believes this unexamined assumption is a critical flaw.

Beyond this (and where I got really hooked), she identifies the primary forces that drive economic growth: “economic life develops by grace of innovating; it expands by grace of import-replacing.” (By “import-replacing,” Jacobs means the process whereby cities begin to produce for themselves what they once imported.)

The value she attributes to innovation, improvisation, and insight and their centrality to her understanding of economic life, seems to make room for artists in the economic scheme of things, even though she seldom mentions artists directly.

She doesn’t say that humans are driven to innovate or imitate, just that when we do, economic life grows.

“The drive to better oneself” – Adam Smith

Adam Smith (1703-1790), whose work is the basis of much classical marketplace economic theory (and who, like Jacobs, apparently reached his conclusions empirically) postulated that the prime force motivating economic life is self-interest, a desire to augment one’s own wealth and to better one’s own condition – which has been turned, by now, into a desire to consume and to acquire. To me, it seems that bettering one’s own condition could have meant lots of things – increasing our knowledge, enriching our spirit, adding and deepening friendships. Instead, our economy has become dependent on acquisition and consumption, and our society has become one that often seems to have little other purpose.

The “drive to better oneself” does not seem to play a strong role in Jacob’s thinking. But I’m not sure. She doesn’t write about it explicitly. Instead, she talks about the mechanisms of economic growth itself, about innovation and imitation (replacing imports) – not about self-interest, acquisitiveness, buying and selling, capital accumulation, or supply and demand. Her notions of economic health (growth and development) aren’t about accumulation, but rather are about energy, the process, initiative, and the generation of new ideas and “new little things.” In a sense, the process is only incidentally about getting bigger. Sometimes economic development (or growth) results in a city getting bigger, but sometimes it leads to renewal or to a reversal of decay and stagnation.

Innovation and inefficiencies

Jacobs has thought-provoking things to say about innovation and economic life:

To be effective as developers and expanders of economic life, she says, cities need innovations (or “inputs of human insight”) and import replacements (or “inputs of human capacity to make adaptive imitations”).

Innovations are made by adding new kinds of work, logically and naturally, to specific bits of older work. When this proceeds vigorously, a settlement becomes a city.

Adding new work to old is full of surprises and hard to predict. The process, she writes, is analogous to a form of logic – intuition – that artists use. It involves being alert to messages in the work being made. The creator must have an insight and make a new departure. Innovation does not emerge from the logic of a customer; it does not come from sales departments.

Innovations are complicated and diverse.

A few of the examples she named are innovations that are part of scientific research at universities and innovations within an existing enterprise, like the dressmaker who developed the brassiere and the mining company that developed many uses for the glue that holds sand to paper.

And also about development and messy inefficiencies:

Development work is messy, consumes time and energy, involves duplication of effort, and is theoretically wasteful. Cities are economically valuable because they are inefficient and impractical.

To stimulate further development, new improvisations and innovations must be continually injected into everyday life.

Conditions that promote efficient production and distribution of existing goods and services are diametrically opposed to conditions that promote economic development.

The period when an organization is most fertile is when it is small. Economic life can expand quickly within symbiotic collections of little messy enterprises, unpredictably and opportunistically changing in content.

Developing new work at a high rate, Jacobs says, requires access to much inefficiently dispensed capital (perhaps developing new art requires the same).

In a large organization nearly all the divisions of labor must be sterile. That is, they can’t actively add new kinds of work. If they did, the organization’s “community of purpose” would vanish. Even in nature, when an organism becomes complex, it keeps its reproductive cells confined to one small part of the organism only. Large organizations likewise set up specific “reproductive organs” – research and development departments. (When we who are concerned about artists and new work use “research and development” as our metaphor, we’re using a concept that’s borrowed from large organizations rather than from small messy enterprises.)

“The great cold of poverty”

“The great cold of poverty and economic stagnation is the absence of economic development,” and this economic process is rooted in the development work that goes on in impractical cities, where one kind of work leads inefficiently to another. Poverty has no causes, Jacobs writes, only prosperity has causes.

People in government (and large philanthropies) tend to seek sweeping answers to problems rather than bring their minds and resources to bear on a particular small problem in a particular place. Yet, according to Jacobs, the latter is how innovations of any sort are apt to begin – as specific solutions to specific problems in specific places. Nationally- or internationally-mandated solutions are at cross-purposes to development.

The primary economic conflict is not between employers and employees but between people with already well-established economic enterprises and those with new ones. New interests need a “third-hand” as a protector to allow them to get a start, and Jacobs believes this “third-hand” role is best played by governments.

Curiosity and drift

Successful economic development, Jacobs says, must be open-ended rather than goal-oriented. It must make itself up as it goes along. It must drift. It must be “an improvisational drift into unprecedented kinds of work that carry unprecedented problems, then drifting into improvised solutions, which carry further unprecedented work carrying unprecedented problems…” (Ellipsis is hers.) Goal-oriented, strategic planning assumes economic life can be conquered, mobilized, bullied – which works if the activity is warfare, but not if it is development. The last chapter of her book is titled simply, “Drift.”

Cyril Stanley Smith, quoted in Jacobs’ book, writes that necessity is not the mother of invention, rather necessity takes advantage of invention. Invention proceeds from something much more like aesthetic curiosity. Most minerals were discovered for use as pigments, Smith claims. Metallurgy began with the making of beads and other ornaments. Techniques for casting cannons were based on a technology developed to make bells. Further, big things grow from little things. New little things can be destroyed by their environments unless they are cherished for reasons more like aesthetic appreciation than like “practical utility” or success in the marketplace.

“Discoveries often happen on the way to something else.”

There is an order to the drift of economic life as it grows and expands, but it is not the order of challenge and response more common in the military. Rather, the order is more like biological evolution. The more niches filled within a given ecology, the more efficiently that ecology uses energy and the richer it is in life and the means to support life. Similarly, economies that produce amply and diversely for their own people and for export, are better off than economies that are specialized.

In addition to innovation, many other things are needed in an economically vital city – energetic adaptation and replacement of imports, a cluster of cities of the same size with which to trade, sources of inefficient and unorthodox capital for new little ventures, and a “third hand” that protects new ventures from established ones.

What about artists?

Artists and artist “incubators” are additional sources of innovation that were not on Jacobs’ mind. They need investments and nurture, too, and not for their practical utility.

“Friends of the Rag” was a loosely-knit group of between 20 and 50 artists, clothing designers, costume artists and artists making wearable sculpture who were active in Seattle in the mid ’70s. While it would be difficult to prove that these artists were in any sense directly responsible for the emergence of a strong fashion industry in the area, they may well have played a critical role in generating the energy that made Seattle a place for innovative fashion, clothing design, and imaginative costumes. They changed the atmosphere, the spirit and the overall sense of creativity and potential in the Seattle clothing world. They infused it with imagination and innovation.

Innovation, invention, and especially aesthetic curiosity are traits that are being specialized right out of our culture, and the trend may be intensified by the separation of artists into their own worlds. Separating artists from the ongoing life of communities (as happens increasingly) might actually be detrimental to a healthy economy. Jacobs wrote in a 1988 letter to me, “By isolating artists or relegating them to the margins of ‘normal’ life, we have also been eliminating from ‘normal’ life traits that are part and parcel of economic development.”

Is the economy of artists different?

How much is an artist’s process like other economic processes? Are the two similar, just in different realms? Or, if we assume that specialized realms once considered distinct often overlap, might we not find that the economics of artists’ worlds overlap with the broader economy?

Instead of speaking just of the “economy,” economic writers often refer to the “political economy” based on the assumption that the two (politics and economics) cannot be separated and that politics is not distinct from economics. Can creative or cultural concerns be separated any more easily from either politics or economics? What phrase might we use to reflect the reality that creativity and culture also are not distinct from the realms of economics and politics, and vice versa – maybe “political and cultural economy” or “creative political economy”?

How can we create ways to support the messy, inefficient work of artists and inject it into everyday life in specific places? In Jacobs’ terms, economic development occurs when cities “produce amply and diversely for their own people, as well as for others.” Isn’t there the chance that, in some inefficient and open-ended way, this will help cities increase their ability to produce amply and diversely for their own people, as well as for others?

Ways we could take action

We could learn from percent-for-art/public art programs that establish diversionary “toll gates” that direct to art work a small percentage of the money flowing to capital projects of various governmental jurisdictions. Presumably, this money feeds and nourishes the capital projects through artists’ work, as well as feeding and nourishing the artist. Using this experience, we could learn how “economic development” dollars work and where they flow within private and governmental agencies. Then we could set up similar toll gates and direct some of the money to artists, supporting them to nurture economic development with their energies, in the messy and inefficient way that Jacobs suggests.

We could provide a place for artists in “business incubators.” These facilities (sometimes governmental, sometimes private, sometimes university-based) provide work space, support, and working capital for new little ventures.

We could find places and roles for artists in private enterprises as well – in the research departments of large companies, in partnership with small innovative companies, and in collaboration with other inventors and scientists.

We could involve artists in the economic development process in other ways – make it more like an artist’s process. How could artists participate in setting economic policy and in deciding where economic development dollars flow?

And, just to repeat what Jacobs told me in her 1988 letter . . .

By isolating artists or relegating them to the margins of ‘normal’ life, we have also been eliminating from ‘normal’ life traits that are part and parcel of economic development.

««««««•»»»»»»

1 “City Views: Urban studies legend Jane Jacobs on gentrification, the New Urbanism, and her legacy,” interview by Bill Steigerwald, Reason.com, June 2001, the quotation I use is on the last page. <jane jacobs interview Reason mag>

![]()

We begin with a topic and a bit of background, but then pose questions to prompt conversation among the small groups. Though it’s easy for the conversation to turn to big, fairly abstract ideas, we’re urged to tie big ideas to our own daily lives.

We begin with a topic and a bit of background, but then pose questions to prompt conversation among the small groups. Though it’s easy for the conversation to turn to big, fairly abstract ideas, we’re urged to tie big ideas to our own daily lives. At the end, we reconvene as a whole to share highlights from each table, and that typically leads to more questions, more conversation, and an energy that’s often hard to stop. Notes collected at each table provide a basis for a summary which is subsequently posted online.

At the end, we reconvene as a whole to share highlights from each table, and that typically leads to more questions, more conversation, and an energy that’s often hard to stop. Notes collected at each table provide a basis for a summary which is subsequently posted online.

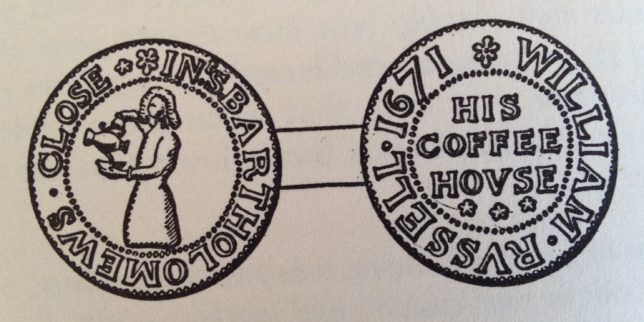

One evening, for example, we had employed workers, a couple of students, and several people who have retired though still working on some level. Among the kinds of work done by people in the room, there were artists and writers, an architect, geographer, engineer, barista, Lighthouse for the Blind worker, foster parent for dogs, and a retired carpenter, financial advisor, and stock broker. The status of their employment also varies – full-time, part-time, temporary, volunteer, independent contractor, and not working. Like early penny universities, we mix interests, ages, fields, incomes, and cultures for face-to-face conversation about things that matter.

One evening, for example, we had employed workers, a couple of students, and several people who have retired though still working on some level. Among the kinds of work done by people in the room, there were artists and writers, an architect, geographer, engineer, barista, Lighthouse for the Blind worker, foster parent for dogs, and a retired carpenter, financial advisor, and stock broker. The status of their employment also varies – full-time, part-time, temporary, volunteer, independent contractor, and not working. Like early penny universities, we mix interests, ages, fields, incomes, and cultures for face-to-face conversation about things that matter. Often someone else’s words describe something so well that the words become a reliable reference point. In pursuing my curiosity about the nature of work, the following passage has done this for me. It appears in “An Interview with Rebecca Brown,” by Alex Davis-Lawrence, which is published in Moss, Volume One.1 After speaking about why and how much she loves it, Rebecca says this about teaching…

Often someone else’s words describe something so well that the words become a reliable reference point. In pursuing my curiosity about the nature of work, the following passage has done this for me. It appears in “An Interview with Rebecca Brown,” by Alex Davis-Lawrence, which is published in Moss, Volume One.1 After speaking about why and how much she loves it, Rebecca says this about teaching…