Report from Penny U, part 2

Basic income – from details to the big picture

If basic income is a good idea, where would the money come from? And what drives the need for more equitable income?

This is the second set of notes from a Penny U conversation in March 2016. An introduction to the topic overall and the first set of discussion notes is here. Those notes discussed ways a basic income might affect or be affected by who we are as human beings . . . for instance, would it affect our sense of self worth?

These notes cover groups who instead focused on specifics such as, if basic income is a good idea, where would the money come from and should everyone get the same amount? Others took up a big picture view that considered society as a whole: are proposals for a basic income just attempts to mitigate capitalism, and why are we having this discussion now?

How would a basic income work?

Can we find the funds? Should everyone get the same amount, or should there be prerequisites for getting the money??

One group was quite optimistic about funding. “We could go back to a truly graduated income tax and levy a large tax on high levels of income or capital gains. We could institute Thomas Piketty’s global wealth tax. We could use the War Tax. We could democratize the workplace by creating more co-ops.”

“The amount of a universal basic income would not be enough to live on, so we’d need a hybrid approach.”

“In Brazil a basic income for families comes with incentives or requirements for doing certain socially positive things, like ensuring that children attend school and be vaccinated.”

“A German experiment with basic income requires an assessment of kids at a certain age, which raises a potential pitfall of people getting pigeonholed into a predetermined role or job when they’re young.”

“The question of prerequisites points to a distinction between the term ‘universal basic income,’ which means unconditional income with the same amount given to all, and the term ‘minimum basic income,’ which asks for proof that you need it.”

“Does universal basic income conflict with the goal of racial and gender equity, since women and people of color historically start with fewer assets? Should they get more?”

“Perhaps we could pay wages for housework as an alternative to giving basic income.”

“A danger is that universal basic income sounds new and exciting compared with the tired old social welfare language. A libertarian view would replace all social welfare programs with a basic income. Leave the choice of what to spend money on to the individual. Appeal to ‘American individualism’, and to our ‘freedom as a consumer’.”

“What we really need is a universal basic income with social welfare underneath, not instead of – a hybrid approach.”

More and more questions

“Would drug and alcohol addiction be more likely with an unconditional basic income, or would people be freed from stress, making it less likely they’d need such substances?”

“Would a basic income allow people to remain on or reclaim rural areas?”

“How big an impact would it have on a global economy? Should it be implemented on a global or a regional scale?”

“Is basic income an authentic solution for communities in distress? What would it mean for communities of color? Would it exacerbate gentrification?” “How universal is this idea? Is it just a white-guy dream of exploring the universe in a post-capitalist world?”

It has to be a dream on top of a broader social movement.

“Basic income isn’t really a political program with a coherent organizing concept that people can come together around. It has to be a dream on top of a broader social movement.”

“It would be exciting if basic income could it be used as a basis to begin building a local economy, to develop a cooperative way to aggregate the funds. We could grow the community by spending locally, and we’d feel connected to our neighbors.” “Working cooperatively confronts the myth of individual achievement.” “This would be easiest if the payments came in lump annual sums rather than smaller monthly payments. We’d need cooperative banks.”

“It all comes down to organizing.”

How would any of this actually get implemented? “It all comes down to organizing.”

The big picture: considering capitalism and the whole society

“Questions about a basic income can’t be asked without considering the whole of society, its conditions, and what really counts. It depends on effects we can’t predict.” “It’s designed for a Keynesian economy that doesn’t exist.”

Is a universal basic income radical enough?

“Discussing a universal basic income raises the question of what capitalism means. And, would universal basic income just be a mitigation?” “Like many other proposals, providing a basic income is a concession to capitalism. A market place would need to exist on top of it, along with continuing differences in wealth.”

“This country’s obsession with individualism is based on a flawed understanding of the history of our economic reality. Resource exploitation and slavery established the basis of our economy and gave us a wildly unrealistic sense of the power of individual efforts.”

We don’t have successful examples. Right now, a basic income would be a pure experimentt, like the Soviet Union’s experiment of taking a feudal Russia directly to communism.

“Perhaps trying to implement a basic income in a society with such a well-established social economy as the U.S. is a bad place to start. Some other kind of base might have to be established first. We just don’t have successful examples.”

“We’ve ceded public responsibility to the private sector, basically selling off the public. And this has been going on since the ‘80s. Would a basic income, paid for by eliminating social welfare/safety net programs, open up the possibility to finish the job quickly? to just drown the baby – that is, government, maybe even democracy?”

Why are we having this discussion now? What drives the need for equitable income?

Two common responses provided a kind of backdrop: 1) the rise of automation that is destroying people’s jobs and 2) the increasing income gap. These two background causes seemed to be accepted by everyone, but conversations went from there.

The only reason we’re even discussing this now is to prevent social upheaval.

“It comes from necessity. We need a new version of the Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal. Understanding the history of the New Deal could help it happen now.” So, how did that come about? “Eleanor Roosevelt and Frances Perkins just kept pushing him forward, and eventually he got on board.”

In his message to Congress on the State of the Union in January 1944, Roosevelt introduced what has come to be known as his “Second Bill of Rights,” or “Economic Bill of Rights.” In introducing his eight rights, he said: “We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence.”

People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made. – Franklin Delano Roosevelt

Penny U participants went on to talk about conditions today: “Both the private sector and government are worried that if jobs are eliminated, there would be overwhelming discontent.” “It’s possible that the private sector will get the incentive to establish and fund a basic income so people will have an income and be able to buy private sector products.”

“There’s momentum for this now. The left is interested and beginning to organize. The tech world is optimistic and getting into the act. Who knows? New markets might be formed. There are many unknowns.” “We need to start creating jobs in a whole different format.”

“The best and quickest way to solve all this would be by electing Trump. The youth are very anti-establishment. ‘Bern it up, or burn it down.’ Take the system and ameliorate it, or burn it down.”

We can’t just ask for this. We have to repair our democratic power first.

“There’s so much to do! Can social pressure encourage people to get involved? Lots of people have a sense of duty. Can we build on that?”

References

Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Second Bill of Rights” ushistory.org/documents/economic_bill_of_rights.htm

The Roosevelt I Knew, by Frances Perkins bestpossiblelife.wordpress.com/2011/06/29/frances-perkinss-book-the-roosevelt-i-knew-reissued-as-a-penguin-classic/

![]()

![]()

![]()

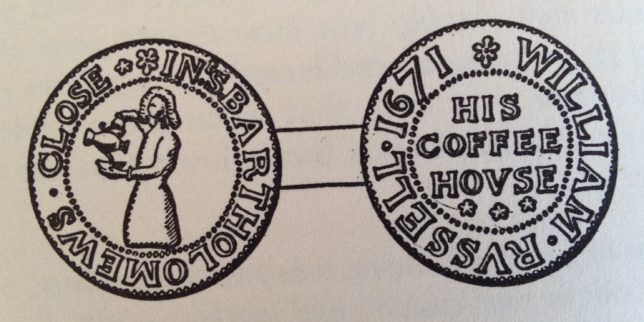

We begin with a topic and a bit of background, but then pose questions to prompt conversation among the small groups. Though it’s easy for the conversation to turn to big, fairly abstract ideas, we’re urged to tie big ideas to our own daily lives.

We begin with a topic and a bit of background, but then pose questions to prompt conversation among the small groups. Though it’s easy for the conversation to turn to big, fairly abstract ideas, we’re urged to tie big ideas to our own daily lives. At the end, we reconvene as a whole to share highlights from each table, and that typically leads to more questions, more conversation, and an energy that’s often hard to stop. Notes collected at each table provide a basis for a summary which is subsequently posted online.

At the end, we reconvene as a whole to share highlights from each table, and that typically leads to more questions, more conversation, and an energy that’s often hard to stop. Notes collected at each table provide a basis for a summary which is subsequently posted online.

One evening, for example, we had employed workers, a couple of students, and several people who have retired though still working on some level. Among the kinds of work done by people in the room, there were artists and writers, an architect, geographer, engineer, barista, Lighthouse for the Blind worker, foster parent for dogs, and a retired carpenter, financial advisor, and stock broker. The status of their employment also varies – full-time, part-time, temporary, volunteer, independent contractor, and not working. Like early penny universities, we mix interests, ages, fields, incomes, and cultures for face-to-face conversation about things that matter.

One evening, for example, we had employed workers, a couple of students, and several people who have retired though still working on some level. Among the kinds of work done by people in the room, there were artists and writers, an architect, geographer, engineer, barista, Lighthouse for the Blind worker, foster parent for dogs, and a retired carpenter, financial advisor, and stock broker. The status of their employment also varies – full-time, part-time, temporary, volunteer, independent contractor, and not working. Like early penny universities, we mix interests, ages, fields, incomes, and cultures for face-to-face conversation about things that matter.