“Alice Anne”

I was named after my two grandmothers, Alice Ross Crawford and Anne Bosworth Focke. My parents liked the sound of Alice Anne much better than Anne Alice, but Alice lived with us for most of my life through high school and having two Alices in the house would be confusing. Whenever my parents felt I needed a strong talking-to, they called out both names. And these were almost the only times I heard them together. So, except as warning or reprimand, I was Anne.

I developed strong attachments to literary and historical figures with each of these names, girls who led colorful, exciting lives. I was called Annie as a kid, and two Annies especially fascinated and influenced me. One was Annie Oakley, a famous sharpshooter in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and featured in Irving Berlin’s musical Annie Get Your Gun, which I heard as a girl at San Diego’s Starlight Opera. (Recalling this, Annie’s song, “Anything you can do, I can do better,” is now stuck in my head.) A second seminal Annie was Little Orphan Annie of the long-standing comic strip, who in the background had a protector, Daddy Warbucks, and who foiled evildoers by herself with her dog Sandy.

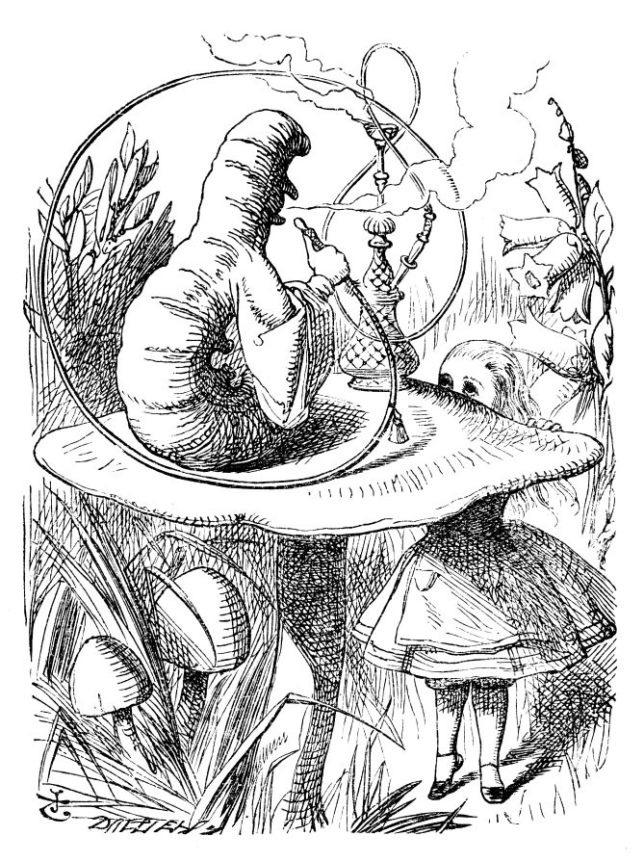

The most influential of my heroines, though, was probably Alice from Alice in Wonderland. She never seemed afraid and instead was simply curious. She followed the White Rabbit in a hurry and fell down a rabbit hole. She landed in a strange and magical place where she got larger and smaller, swam in a pool of tears, shook hands with a dodo bird, watched Father William balance an eel on his nose, conversed with a hookah-smoking caterpillar on a large mushroom, watched the smiling Cheshire Cat in a tree disappear, had tea with the Mad Hatter and Hare, tried to play croquet with a flamingo and a hedgehog, and had to testify before the court of the fearsome Queen of Hearts.

I went on those adventures with her while my dad read the stories aloud. Her story and Sir John Tenniel’s original illustrations provided beginning points for imaginations of my own Although Tenniel’s drawings are the source for my strongest visual memories of the story, I’m sure the characters in Walt Disney’s movie have a role in my memories as well.

![]()

Alice, Annie, and Annie taught me the special powers of imagination, believing in myself, and the thrill and adventure of catching evildoers.

My grandmother Alice died after I left for college. From my youngest brother Ross’s brief descriptions of her last years, I now assume she died with dementia or Alzheimer’s. Years later, my mother did also. Looking back on it all now, I’m saddened by how distant I was from Gran’s death and in many respects from Mom’s death as well. She died in 1997. My brothers Frank and Ross – especially Ross – were the true caretakers of my mom in her last years. They’ve become bright stars for me as I remember their caregiving role.

The few times I was with Mom by myself toward the end of her life, I remember wondering how to enter her world of dementia. I felt I had to be carefully present-tense, consider things that were right in front of us, that we could see and touch, not things that happened yesterday or that might happen tomorrow. Being unable to remember yesterday or think about tomorrow made her feel bad or angry and just increased her confusion. I didn’t understand the disease well enough to know that if we’d jumped much further back in time, we might have opened up older, more enjoyable memories for her and for us both.

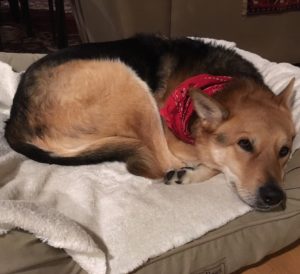

![]()

Perhaps influenced by my Alice-in-Wonderland past, I’ve always found it easy to jump beyond present circumstances, imagining ways of being that might be but aren’t yet. I wondered how I could see my mom’s and her mom’s dementia – perhaps my own in the future – as interesting or useful, or simply as another acceptable way of being. I thought about historical tales of the wise fool, the wisdom of the village idiot, the ancient oracles, or the mystic seer.

Today dementia is an evildoer. At a 2010 symposium of designers and developers of senior housing, a speaker referred to dementia and Alzheimer’s disease as the biggest fear of aging boomers, a fear he urged his colleagues to acknowledge.1

What are we losing by not including in our lives – personally and societally – relationships with and insights from people who seem to exist in other realities? Are we losing their special powers in our super-rational world? How do we understand the edges dividing dementia and wisdom?

![]()

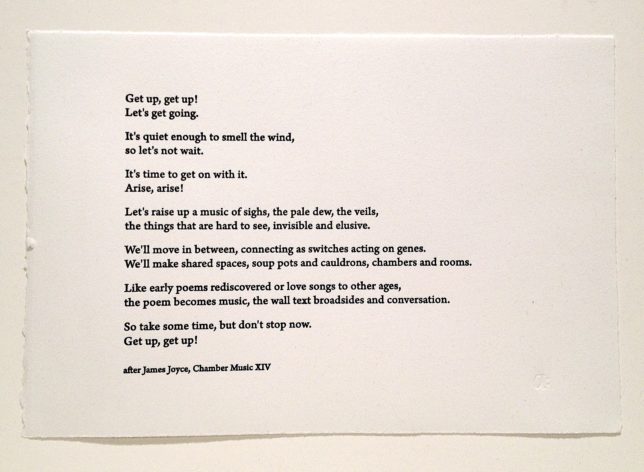

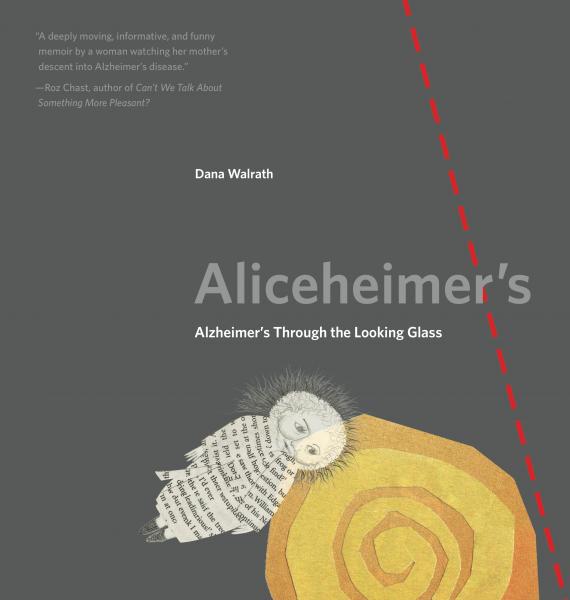

A year or two ago, I discovered a book by Dana Walrath, Aliceheimer’s: Alzheimer’s through the Looking Glass.2

In Aliceheimer’s, Walrath, a medical anthropologist, graphic artist, and writer, tells the story of her mother Alice’s journey with Alzheimer’s, especially during the two years when Alice lived with Dana and her husband in their Vermont home. In the introduction, Walrath says that the biomedical story of dementia “is in desperate need of revision.”

The dominant narrative is a horror story. People with Alzheimer’s are perceived as zombies, bodies without minds, waiting for valiant researchers to find a cure. For Alice and me, the story was different. Alzheimer’s was a time of healing and magic. Of course, there is loss with dementia, but what matters is how we approach our losses and our gains. Reframing dementia as a different way of being, as a window into another reality, lets people living in that state be our teachers – useful, true humans who contribute to our collective good, instead of scary zombies.

Wow, I thought. I’ve been waiting for this. Perhaps this begins to show how to slay the evildoer.

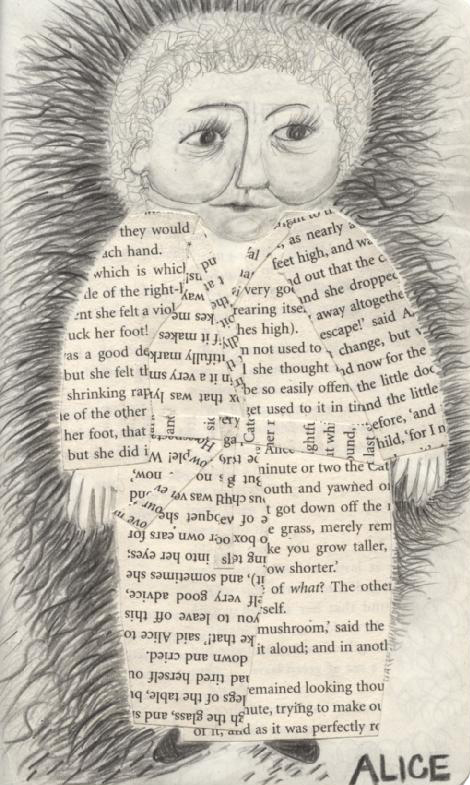

Alice in Wonderland seems to be as important to Walrath as it was to me. She uses Lewis Carroll’s book as an emotional frame for her book. “I found the story’s voice the day I cut up a cheap paperback copy of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, using the page fragments to make her bathrobe, Alice’s favorite garment.” Alice falls slowly down the rabbit hole of her memory loss and disappears gradually like the Cheshire Cat.

Walrath’s book is part of the Graphic Medicine series.3 She chose the graphic narrative form in the belief that it could reach someone with dementia. She writes, “Graphic storytelling captures the complexity of life and death, of sickness and health. Going back and forth between the subconscious and conscious, between the visual and the verbal, lets us tap into our collective memory, an essential element of storytelling.” It allows us to “better understand those who are hurting, to feel their stories, and redraw and renegotiate social boundaries.” She made her Alice drawings in part “to process my own grief after placing my mother in an Alzheimer’s residence…. But I was also drawing to remember the magic and laughter of that time.”

With a community of help that included pirates, good neighbors, a cast of characters from space-time travel, and my dead father hovering in the branches of the maple trees that surround our Vermont farmhouse, Aliceheimer’s let us write our own story daily – a story that, in turn, helps rewrite the dominant narrative of aging.

Most of the book alternates between graphic and written pages, each two-page spread telling of a day in Alice and Dana’s world.

“Dana, am I going crazy? You would tell me if I had lost my marbles, wouldn’t you?”

I’ve heard these questions many times. Repetition. Anyone who lives with Alzheimer’s knows from repetition. As her rudder, I always supplied Alice with the same steady answers. “No, you’re not crazy. You have Alzheimer’s disease so you can’t remember what just happened.”

“Oh. I forgot. What a lousy thing to have.”

One story, early in the book, tells of Alice losing her home. The accompanying drawings count Dana’s days with Alice. “Alice is disappearing. Soon there will be none.”

Often the “internal governor” of people with Alzheimer’s also disappears; they say exactly what’s on their mind. This disappearance lets new things appear. Alice found parts of herself that she had kept hidden, from her children anyway. She wished out loud that she had gone to medical school instead of becoming a biology teacher. Her years of pushing me in this direction and away from creative work made sense at last.”

One of the reasons Walrath moved Alice into her home was “our unfinished business of finding a good close.” They had never been close. In gentle, surprisingly direct ways, they found resolution, “at last.” After one quiet but deeply felt exchange of apology and forgiveness, Walrath writes, “I knew that if I wanted it, Alzheimer’s would let us have this conversation every single day.”

![]()

Alice remembers all the songs from The Music Man and countless others from her youth. The present is more elusive. These days she doesn’t remember that she has Alzheimer’s. But she used to. And she always sings.

One May morning, she stood by my dining room windows, looking out over the rolling field, and she sang this bit from Babes in Arms:

It seems we stood and talked like this before

We looked at each other in the same way then,

But I can’t remember where or when.

The clothes you’re wearing are the clothes you wore.

The smile you are smiling you were smiling then,

But I can’t remember where or when.She stopped and she smiled and said, “That should be the Alzheimer’s theme song.”

Aliceheimer’s.

![]()

As a medical anthropologist, Walrath’s broad, cultural and historical understanding of sickness and health reaches beyond the medical system that so dominates the understanding of health in the U.S. today. She writes in her introduction:

Biomedicine locates sickness in a specific place in an individual body: a headache, a stomachache, a torn knee, lung cancer. Medical anthropologists instead locate sickness and health in three interconnected bodies: the political, the social, and the physical.4 The prevailing political economy impacts the distribution of sickness and health in a society and the means available to heal those who are sick. …The social body constructs the meanings and experiences surrounding certain physical states.

Some cultures locate sickness not in individuals but instead in families or communities. As any caregiver knows, we live the sickness too. And while biomedicine can cure diseases, it flounders with permanent hurts, troubles of the mind, states present from birth or that are incurable or progressive. In biomedicine, these states are stigmatized and feared. We medical anthropologists have a term for this: social death.

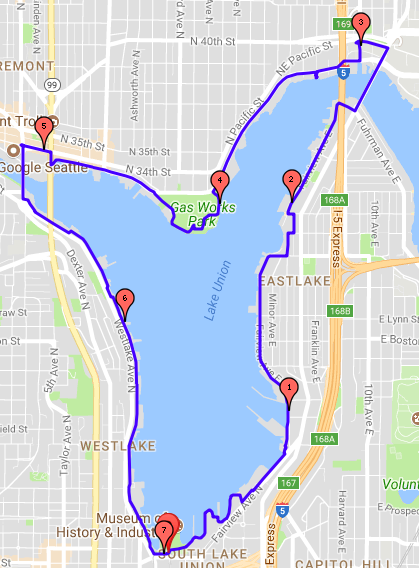

The role of “social bodies” – that is, communities – in the health of individuals is being discovered and described more and more often. Alzheimer’s is one kind of “social death,” and British writer George Monbiot identifies another. Loneliness and isolation constitute a “disease of epidemic scale today,” he writes in Out of the Wreckage: a new politics for an age of crisis.5 “Of all the fantasies human beings entertain, the idea that we can go it alone is the most absurd and perhaps the most dangerous.” Monbiot is constantly on the lookout for ways to combat this disease. He begins a recent column for The Guardian, “The town that’s found a potent cure for illness – community,” this way: “It could, if the results stand up, be one of the most dramatic medical breakthroughs of recent decades. It could transform treatment regimes, save lives, and save health services a fortune. Is it a drug? A device? A surgical procedure? No, it’s a new-fangled intervention called community, as results from a trial in the Somerset town of Frome [England] show.6

Although Monbiot warned that the findings are based on what he termed “provisional data” – that is, not yet published by the academic press – he also wrote that “this shouldn’t stop us feeling a shiver of excitement about the implications.” Results of the Compassionate Frome project, begun five years ago, appears to show that when isolated people who have health problems are supported by community groups and volunteers, the number of emergency admissions to hospital falls dramatically. Sometimes the help took the form of handling debt or housing problems, sometimes joining choirs, lunch clubs, exercise groups, or writing workshops. The point was, he said, “to break a familiar cycle of misery: illness reduces people’s ability to socialize, which leads in turn to isolation and loneliness, which then exacerbates illness.”

![]()

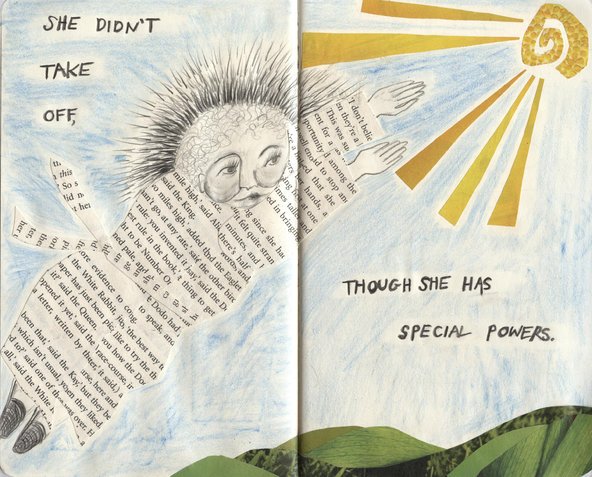

When [Alice] was certain that her own mother, who died in 1954, had just been sitting on the sofa in the living room and talking with her, she would say, “You see her, don’t you?” I’d say, “I can’t see her, but I’m sure you can. You have special powers. You can see things that we can’t.” For her that was enough.

What Walrath offered her mother was a way to break the familiar cycle of Alzheimer’s misery. And it’s telling, I think, that Dana and Alice’s “wonderland” – the community they made together – offered gifts to them both.

![]()

Notes

1 Robert Kramer, founder and president, National Investment Center for the Senior Housing and Care Industry, speaking at the Senior Housing Design and Development Symposium at the University of Maryland, 2010.

2 Aliceheimer’s: Alzheimer’s through the Looking Glass, Dana Walrath, Pennsylvania State University Press, 2016.

3 Graphic Medicine book series, from the Pennsylvania State University Press. “Books in the series are curated by an editorial collective with scholarly, creative, and clinical expertise, and attest to a growing awareness of the value of comics as an important resource for communicating about a range of issues broadly termed ‘medical’.”

4 From Walrath’s introduction: For more on this see Nancy Scheper-Hughes and M. Margaret Lock, “The Mindful Body: A Prolegomenon to Medical Anthropology,” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, no. 1 (March 1987): 6-41.

5 George Monbiot, Out of the Wreckage: a new politics for an age of crisis, Verso Books, 2017.

6 George Monbiot, “The town that’s found a potent cure for illness – community,” The Guardian, February 21, 2018.

![]()