My brother Francis George Focke died at home in Rancho Cucamonga, California on April 22 in the early months of the 2020 coronavirus pandemic.

When he died, I was out walking in the rain in Seattle. Toward the end of my walk I passed a large camellia tree that seemed to have dropped most of its flowers all at once just before I got there—red camellias all over the ground and sidewalk under my feet. Our family’s house in Claremont, the last place that Frank and our whole immediate family—parents, brothers, and grandmother—lived together, was surrounded by camellias.

Frank died of an aggressive lung cancer that seemed to come up quickly. He’d been a smoker most of his life. I first learned of his cancer when he called to tell me of the diagnosis about a week and a half before he died. It wasn’t until four or five days later that I realized just how much pain he was in. He didn’t talk about his feelings easily (health or otherwise) and avoided focusing on himself. He had planned to have an initial chemo treatment on April 22 and even had a port put in. But on April 20, he just couldn’t bear the pain and discomfort any longer. With his wife Barb, he decided to cancel treatment and let the cancer take its course. His last few days were difficult, but Barb, who was with him, told me he died peacefully, for which I’m grateful.

It was hard not to be there. The miles and the virus kept me away. I was so glad to learn that our brother Ross was able to visit on the evening before Frank died. Seeing Ross again had been one of Frank’s last wishes.

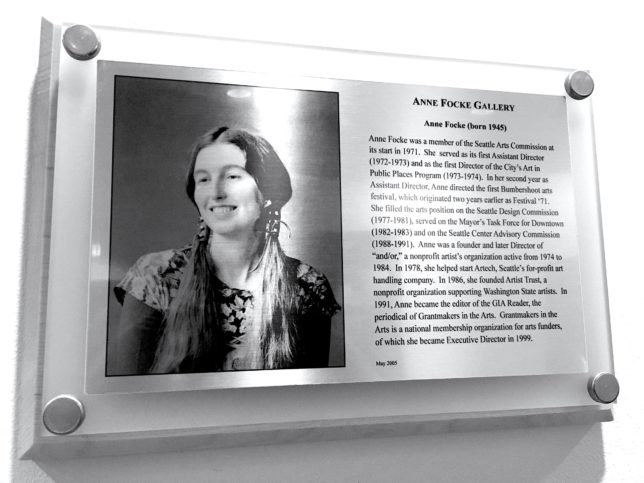

Frank didn’t want any kind of memorial to celebrate his life or mark his passing except a plaque with his name at the cemetery. All the same, memories of him have appeared here and there. Making up for the lack of a formal obituary, I’ve cobbled together a few memories.

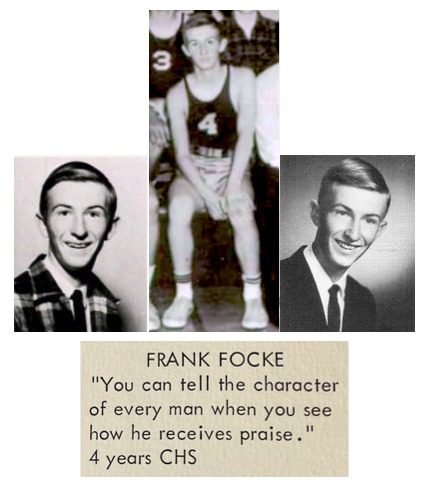

A bit of a cut-up and clown, “Frank-o” was my “middle-est” brother in a string of brothers, whose names will always roll easily off my tongue in chronological order – Fred, Ted, Frank, Karl, Ross. I came along between Fred and Ted for a total of six. The family moved to San Diego in 1945, and Frank was born there in Mercy Hospital in 1948. A collage of photos from about 1957 that I spotted on Frank’s wall shows Mom and Dad with all us minus Fred, who, ten years older, must have been away. Frank is at the lower right.

All of us, along with our grandmother, lived for about fifteen years in a two-story house on Mount Soledad in San Diego, surrounded on the back by hillsides of sagebrush and a valley with a chicken ranch and a dairy farm at the bottom. In front we were connected by dirt roads to nearby friends, a cactus ranch, and flower farmers. It was a great place to be young, perfect for building hide-outs, bringing baby chicks home, learning how to get lost and found again. The family moved north to Claremont in 1959, and except for Fred we all attended and graduated from Claremont High School.

An “In Memory” entry on Claremont High School’s Alumni Society website includes year-book photos of Frank (class of 1966) and comments from fellow classmates who described him as “such a great guy and so quiet and gentle,” “nice and friendly,” and “one of the good guys.” To inform their mutual friends, Ross posted a notice of Frank’s death on his Facebook page. It included a photo with this caption: “My brother Frank at boot camp in the Marines 1967. He was a helicopter mechanic in the Vietnam War close to the DMZ. He was proud, he was a Marine.” He was nineteen.

A clipping included on the Alumni site and probably published in the Claremont Courier, reported “Marine Lance Cpl. Francis G. Focke, 20, is serving with Heavy Helicopter Unit 462 in the 1st Marine Aircraft Wing in Vietnam. His unit operates several hundred aircraft including fighters, attack and reconnaissance craft, and helicopters. The Wing last year was awarded a Presidential Citation for combat achievements.”

Lance Corporal in the Marines is equivalent to a Private First Class in the Army. I remember Frank telling me, a few years after he returned, that he was rather proud of not rising to a higher rank during the years he served. He did his job, did it well, and kept his head down.

Before he died, Frank sent a box containing a few items from his Marine days to Heather, his favorite granddaughter, more accurately, a step-granddaughter who came into his life through his second wife, Priscilla. One of the items in the box was a large coin. Research identified it as a Vietnam Veterans Welcome Home Challenge Coin.

Ross’s Facebook post attracted comments from family and mutual friends. Some of them knew him from the days, after the Marines, that he spent as a bartender at the Midway Tavern, between Claremont and Upland on Route 66. Michael wrote:

That Marine Mentality would come FLASHING to the surface from time to time. One night a fight broke out at the Midway and I was sitting at the middle table between the front wall and the pool table. One of the fighters spotted me and came RUNNING towards me. I was thinking ‘Oh man, the shit’s ON,’ when I heard this metallic clank right above my head. There was Frank standing right behind me. He had grabbed one of those metal folding chairs and snapped it into the folded position and he was IN THE STANCE, holding inches from the guy’s face.

Frank was always there for me.

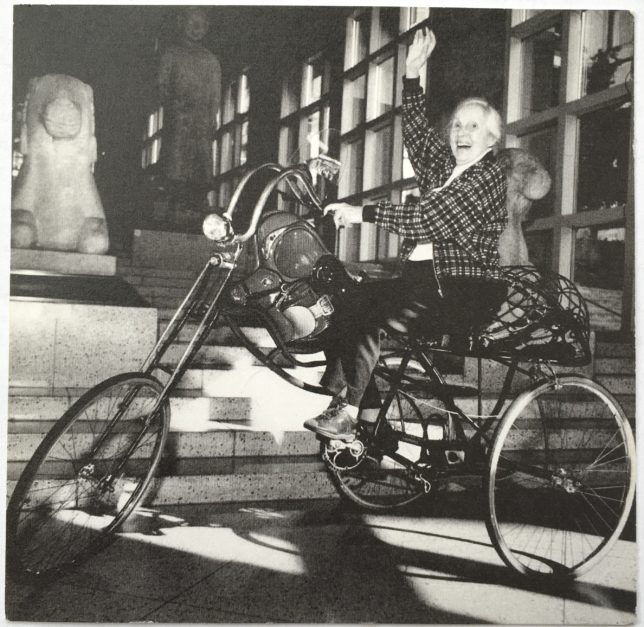

Other Facebook posts with brief memories and condolences came from cousins, his first wife Lupe, and other old friends from Claremont, including Ruth, who added this picture of Frank pouring beer at the Midway.

Frank lived with alcoholism and went on the wagon at least 30 years ago. A few years after he quit, he told me the craving never stopped, but whenever the desire got hard to handle, he’d tell himself, “You can have a beer tomorrow.” And, as far as I know, that tomorrow never came..

In 1998 Frank and Priscilla moved to Casa Volante, a 55+ mobile home park in Rancho Cucamonga right off Route 66. At 50, he wasn’t old enough to live there on his own, but Priscilla qualified. Casa Volante is a quiet park with winding streets, about 200 homes (which they call coaches), a clubhouse with a small swimming pool, and many trees and plantings that soften the park’s landscape. Frank had been able to buy a coach with proceeds from our mother’s estate, which helped sustain their quiet, carefully frugal lifestyle.

Priscilla died in 2003, and it wasn’t long before Frank and Priscilla’s good friend Barb found each other. They married in October 2005 at poolside behind the clubhouse, surrounded by friends from the park and beyond.

When they were much younger, Frank and our brother Ross worked together on small construction and maintenance projects for home and garden. Frank carried his skill along with an inborn concern and care for others to Casa Volante, and he was known in the neighborhood for fixing toilets, hanging blinds, patching roofs, and running monthly pancake breakfasts and weekly bingo games. He was hired as the park’s assistant manager in 2012.

On one of my visits, I participated in a bingo game. Frank pulled out the large, rolling mechanical bingo board, set up the long tables and all the folding chairs in the main clubhouse room, and brought out the individual bingo cards and pencils. Without much fuss, he ran the show. The room was jammed, every seat taken. I was embarrassingly lucky that day, winning about 27 dollars. Some of my loot I shared with Frank and Barb, and the rest I contributed back to the bingo pot to start the next week’s game.

In their June 2020 message to park residents, Dan and Lou, resident managers, said, “Frank was a fixture in the Park and I still keep expecting him to walk into the office to fill us in on things he observed while on one of his many daily walks.” A remembrance of him filled the other side of the newsletter: Assistant Manager – All Around Handy Man – Our Friend. “Frank was always there for residents: locked out, call Frank; leaky faucet, call Frank; need groceries, call Frank need your dog walked, call Frank. If he could do it, he would. Rest in Paradise, Frank.”

He clearly played a big role in creating community there. He leaves a huge hole in many lives. In a phone call a few weeks after he died, Barb told me that flowers were filling their home. She described one bouquet that had been carefully crafted to incorporate a dismantled piece of the big bingo board. Maybe there were even camellias.

![]()